In the age of streaming, scoring for silent films might seem a somewhat obscure and economically precarious past-time.

Defying the odds are Melbourne-based bluegrass-inspired five-piece Blue Grassy Knoll, who have built a touring career on performing their scores for silent-cinema-era Buster Keaton films from the 1920s, 30s and 40s. It seems that the theatrical alchemy of silent film and score performed live in front of an audience generates something more than the sum of its parts.

Blue Grassy Knoll

‘Three things are going on,’ says Gus Macmillan, Blue Grassy Knoll’s banjo and flute player.

‘There’s the film itself, there’s the band, and then there’s the audience. It has this triangle of energy. We’re bouncing off the film. The film is responding to us as well in a way, and the audience is responding to both. The synergy of it makes for something that’s fairly unique.’

Blue Grassy Knoll (Macmillan, Steph O’Hara, Simon Barfoot, Phillip McLeod and Alex Miller) have been performing their live scores of Buster Keaton films to great acclaim across five continents since a serendipitous turn of events in the 90s.

Blue Grassy Knoll. Image supplied.

‘Someone had told me about a project that they’d seen at the Adelaide Festival some years previously about a live accompaniment to a silent film,’ Macmillan says. ‘And I thought: wow, that sounds like something I would really be interested in trying.

‘My girlfriend at the time was a film student, and I said, “Who do you reckon? What film do you reckon would be good to score to?” And she said the best film she’ saw all last year’d seen in her previous year at film school was Our Hospitality (1923) by Buster Keaton. I’d never heard of it.’

After a whirlwind six weeks of a ‘delightfully analog, very organic’ experience composing their score, Blue Grassy Knoll went on to perform it to Our Hospitality at the 1996 Melbourne Fringe Festival.

‘It was astounding how much laughter there was in the crowd from people seeing it for the first time, because of course, by that point, you’ve stopped laughing at it because you’re so busy trying to remember what to do next and just play it.’

Since then, Blue Grassy Knoll have composed scores for seven more of Keaton’s films, as well as the 1922 Chinese comedy short film Labourer’s Love.

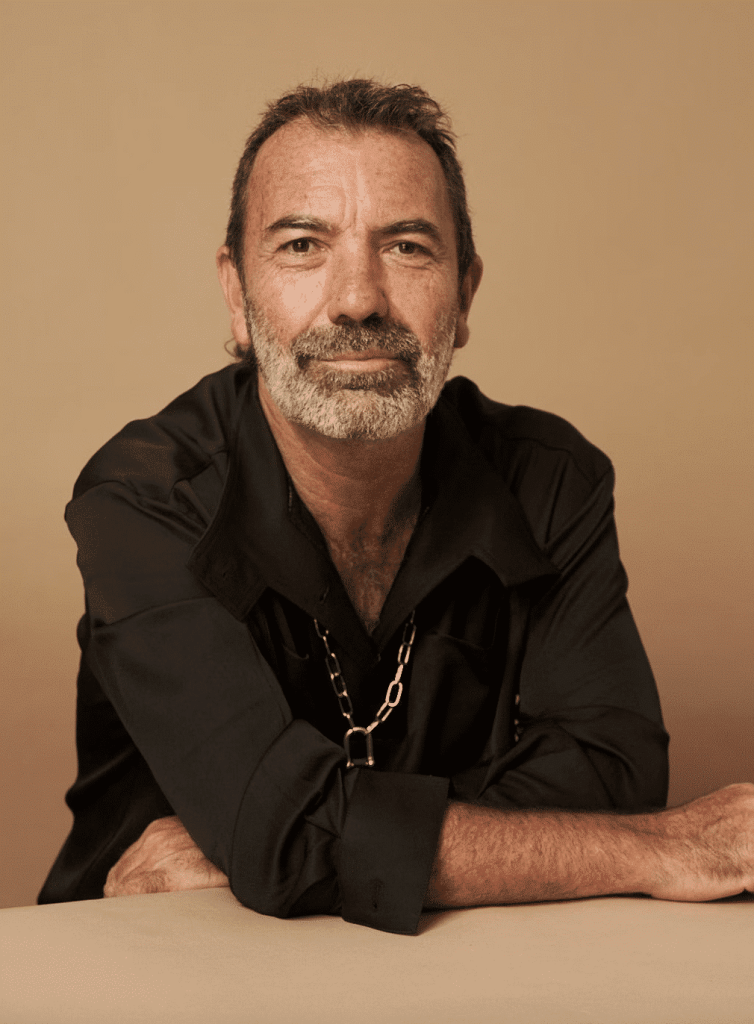

Paul Mac

Former Dissociatives member Paul Mac is best known as an electronic artist and singer-songwriter, having been a touring member of Silverchair and winning an ARIA for Best Dance Release in 2002 for his track 3000 Feet High. Creating the original score for 1919 Australian silent film The Sentimental Bloke was an act of happenstance, he says.

‘The National Film and Sound Archive got in contact with me, saying they’d restored the film [for the film’s 100th anniversary] and they wanted to commission a new score for it and a live performance.

Paul Mac. Image: @mica_chutrau

‘I thought: how do I even approach this? It’s just relentless. It’s just music, music, music the whole way. And it’s also a question of, well, what does it sound like? It’s from 1919, so I didn’t want to get stuck in that period, but it had to feel like it matched.”

Peter Knight

Contemporary composer and jazz-trained trumpet player Peter Knight has worked with multi-instrumentalist Dũng Nguyễn, Minh Ha Patmore, Erik Griswold and Vanessa Tomlinson previously to compose the work 1988 for Australian Art Orchestra in 2020, and presented this work for the 2023 OzAsia Festival in Adelaide.

When he was approached by InsiteArts to compose for a series of silent surreal and Dadaist short films, he immediately thought of this ensemble.

Peter Knight. Image: Sarah Walker.

‘Dũng is a great jazz guitarist, but he grew up learning Vietnamese traditional music from his grandfather in rural Vietnam,’ Knight says. ‘And if you’ve ever heard any Vietnamese music, they have the most extraordinary instruments. There’s a single string zither called đàn bầu. Minh Ha Patmore plays this extraordinary percussion instrument called the đàn tre, which is made of bamboo. It hangs from this frame, and it looks a bit like a whale skeleton.

‘These instruments look beautiful and they sound really unusual. That’s combined with my approach to trumpet and electronics and using old tape machines. And Erik Griswold, who’s a piano player who’s going to be preparing the upright piano, so the piano doesn’t quite sound like a piano. And then Vanessa Tomlinson, who’s also a beautiful percussionist, will be playing vibraphone and drum kit and other found instruments.

For Paul Mac, the sounds he would eventually use for The Sentimental Bloke emerged through experimentation and practical decision-making.

‘I decided to use acoustic instruments and woodwind and brass and play the piano a lot, which is something I hadn’t done for years. So it was like, OK, that’s my palette, with a sprinkling of electronic stuff for fun and additional colour.

‘I started on the piano, got a friend who plays guitar and banjo, and then just started demoing that and building. Often it happens that throughout that process, I am thinking in the back of my mind: I need something that sounds like an oboe or something that sounds like a clarinet. I was just using synth sounds at that point.

‘Once I was working with a real clarinet player, he would say, “Oh, that would sound much better on the bass clarinet.’ And I hadn’t even thought of that. And same with sax. The sax player said, “Oh, I can also play baritone. It would sound honkier down there”.’

Feeling it

When Blue Grassy Knoll composed Our Hospitality, the musicians were in their 20s, playing folky instruments like banjo and fiddle and accordion at rock gigs, with a self-described anarchic streak. They were new to film scoring, and so yet to develop an established process.

‘We were very much feeling our way,’ says Macmillan. ‘And what it enabled us to do was to explore a range of musical styles that wasn’t available to us when we were playing our live pub gigs.’

‘There was a lot of improvising that happened in the early days. The band was looking at the film and saying, right: this is when the girl, Buster’s love interest enters, so we’re going to need some sort of a love theme here. And there’s a big chase scene at the end, so we’re going to need some sort of chase music. The band members would go off and come back with ideas for sections of the film.’

Peter Knight’s compositional process has emerged from his training as an improviser. ‘You’ve just got to keep finding a process that works for you, and it’s different for everybody,’ he says.

‘Some people just imagine things right out of their heads and then write them down in front of the piano. Other people work very conceptually and build up frameworks that come from mathematical ideas or other structural ideas. I like to work from musical materials themselves, and I think that’s probably partly just because the thing that got me excited about music in the first place was improvising.’

‘[The ensemble and I] developed a piece called 1988 [for the Australian Art Orchestra] during Covid. We passed a lot of ideas back and forth via Zoom meetings and Dropbox. Dũng and I would sketch something out and then we would send it to Erik. And then Erik would suggest some ideas, and then he would play something and then send it back. And then we did the same with Vanessa, and the same with Minh Ha.’

Australian Art Orchestra ‘1988’ Creative Development from Australian Art Orchestra on Vimeo.

Different musical scores for The Sentimental Bloke have been written by various composers since it emerged in 1919, but for Mac, creating his original score required a clean slate.

The film is based on the 1915 narrative poem The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke, by Australian writer C.J. Dennis, which gave Mac additional fodder for developing his score.

‘In the film there are overlayed cards, where writing from Dennis’ book features over the footage. I read the book, and it’s really beautiful poetry, but every time one of those cards came up in the film, I’d have to hit pause because the font was really difficult to read.’

The Sentimental Bloke (1919). Image: NFSA.

‘So I thought: OK, this stuff is meant to be heard rather than read. I thought about who a good Aussie voice would be to read it, and reached out to Rhys Muldoon, who I’d met before, and he came and read the cards.’

Washout

While Macmillan estimates Blue Grassy Knoll have performed Our Hospitality more than 300 times since that first performance in 1996 at the Melbourne Fringe Festival, the performance of Peter Knight and Dũng Nguyễn’s score for the program of Surreal Shorts on 20 February at Fed Square will be a world premiere. The first – and only – previous performance of Mac’s composition for The Sentimental Bloke at Sydney’s Westpac OpenAir Cinema in 2020 turned out to be a literal washout.

‘The world’s worst thunderstorm happened during the middle of the film,’ he recalls. People were sitting in ponchos or left. It was just heartbreaking. But we did it, and the people who came said they loved it. That was the only live performance of it. So, it is exciting to have another opportunity to get it heard again.’

And how is he feeling about it? ‘I’ll be nervous as all hell. I know at the end of it, it’ll be a total buzz. And I’m glad that I can hopefully bring some joy to some people in a live setting.’

The Sentimental Bloke (1919, Australia), with live score by Paul Mac, will be performed at Fed Square on 13 February at 8pm. Surreal Shorts with Live Score by Peter Knight and Dũng Nguyễn will be performed at Fed Square on 20 February at 8pm, featuring Meshes of the Afternoon (Dir. Maya Deren & Alexander Hammid, 1943, USA, 14 mins), Anémic Cinéma (Dir. Marcel Duchamp, 1926, France, 7 mins.) and L’étoile de mer (The Starfish) (Dir. Man Ray, 1928, France, 21 mins.). Our Hospitality (1923, US), with live score by Blue Grassy Knoll, will be performed on 27 February at 8pm. Visit Fed Square for more information.

This article is an edited version of Triangle of energy: Paul Mac, Peter Knight and Gus Macmillan on the art of scoring for silent film, published by Fed Square.