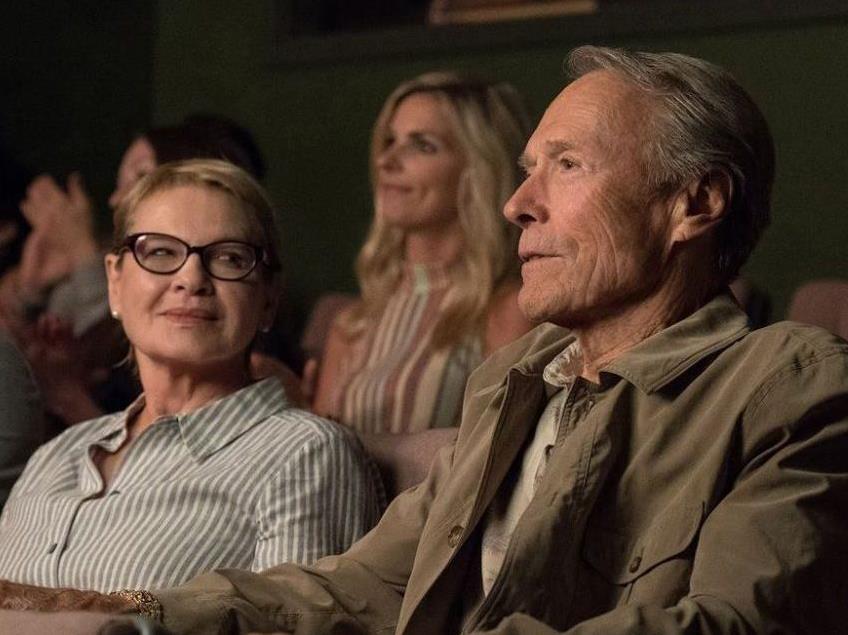

Image: Reconsidering the old man of the screen. Dianne Wiest and Clint Eastwood in The Mule.

Clint Eastwood’s splendid The Mule is a film I’m glad I saw on a big screen. From early on, with the distant, aerial shots of Earl Stone (Eastwood) driving his truck through the landscape, I was sent back, in my memory, to a fine period in American cinema: roughly the first half of the 1970s, when road movies of various kinds (from taut action thrillers to melancholic character studies) knew how to make good use of such expansive views, usually wedded to a stirring orchestral score or an apposite selection of popular music.

In filmmaking, it’s all a matter of comparative scale – those relaxed panoramas of the highway, for instance, contrasted with, and balanced against, the more intimate details of a human story. Eastwood no doubt learned a few tricks in this trade from his early mentors, such as Sergio Leone (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966) and Don Siegel (The Beguiled, 1971), for whom he acted. But Eastwood, over the long haul of his career, has tweaked the film styles of the 1960s and ‘70s to his own ends, and carved out a unique approach.

Watching The Mule, I suddenly realised, for the first time, something essential about Eastwood as a director: he also almost never uses – unless he absolutely needs to – tight close-ups or insert shots. If Earl has a tense moment where he gazes upon the money-filled envelope in his hand or a gun placed near to his head, Eastwood rarely breaks this up into a sequence of ever-tighter shots, as many filmmakers routinely would. Instead, Eastwood trusts us, his viewers, to “size up” the situation ourselves – to weigh the significance of one detail against another, all presented in their total, holistic, dramatic context. That’s why the big screen serves him (and us) so well.

Is it also why those critics favourable to Eastwood like to call him things like “the last great classical director”? More than ever, in The Mule, Eastwood (now 88) plays the game of self-portraiture: Earl is a wily, slow-moving, steady-as-it-goes guy who gets things done by doing them his own way. He’s affable to almost everybody he meets, but harbours disdain for all things “politically correct”. (In one of the film’s loveliest roadside scenes, a couple try to teach him some racial manners: “Look, you’re white and we’re black” – to which he replies, deadpan: “No shit”.)

There is also an aspect here of Eastwood looking back over his own career, and even his own life. In a flashback to 2005 – close to the moment when the director himself received the biggest acclaim of his career for Million Dollar Baby – we see Earl as a flaming star of the horticultural set, feted and adored by all. But Earl has also neglected his wife (superbly played by Dianne Wiest) and kids – and the casting of Clint’s daughter Alison Eastwood as the aggrieved Iris (understandably hurt because Earl didn’t bother to show up for her wedding) strikes an especially melancholic note for anybody who has followed the director’s work over all these years. When Earl says “I’m sorry for everything”, you have to wonder what Clint is secretly confessing to …

I haven’t yet mentioned the two material objects that The Mule is primarily about: drugs, and flowers. Inspired by a true-life case reported in The New York Times, the character of Earl is a guy who falls on hard times, and then, by sheer chance, lucks into a ludicrously well-paying job as a drug mule. He’s the perfect cover: never been served with a ticket for speeding in his life, and the last person anyone would suspect of carrying a drug stash. Earl is so laid-back that he doesn’t even bother to hide the stuff (“You don’t cut up my car!”, he barks at his drug handlers) – it’s just there in a bag, visible in the back of his truck alongside the pecans and other food treats. Just as The Mule brilliantly inverts the premise of the TV series Breaking Bad – involvement with the drug business doesn’t turn Earl into a demonic bad guy like Walter White – it also casually replays, ironically and far less grandiloquently, the meeting of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in Michael Mann’s Heat (1995): here, in a fast food joint, Earl even manages to give Colin (Bradley Cooper), the cop on his tail, some wise work/life balance advice.

The flowers are not for plot purposes, but for dramatic (and comic) metaphor. And nobody does matter-of-fact, understated metaphor like Eastwood! The daylilies that Earl is an expert at cultivating stand for what he most values in life: ephemeral pleasure and beauty, here today and gone tomorrow, an eternal present indefinitely repeated and recommenced. But he discovers, to his distress, that there’s another time-scale which he cannot master: the “long duration” of mortality and irreparable loss. Time, he finally tells us, is the one thing his drug money can’t buy. But – in a further twist of the flower metaphor – Earl discovers the possibility of a second chance and, as Iris suggests, he may, after all, be “a late bloomer”. As in the best Eastwood films, these types of details are skilfully just “dropped in” to the narrative flow at first – and when they resurface, their emotional effect is powerful. (The same goes for the singing and dancing in this film, but you will have to discover the hidden poignancy of Spiral Staircase’s 1969 pop hit “I Love You More Today Than Yesterday” for yourself.)

I’ve alluded a few times already to the large span of Clint Eastwood’s career as a director, from Play Misty for Me in 1971 to now. I will honestly confess that he hasn’t always managed to hold me in as a fan; I’ve lost the faith a few times, at the point of the clunky adaptation of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997), for instance, or the execrable misfire The 15:17 to Paris (2018). But The Mule, almost miraculously, reconciles the director’s “dark side”, as expressed in Unforgiven (1992) and A Perfect World (1993), with the joviality and eccentricity that cinephiles treasure in his least-known gems, Bronco Billy (1980) and Honkytonk Man (1982). It’s true: Eastwood is a late re-bloomer.

In her Screenhub review, Sarah Ward suggested that The Mule projects Eastwood’s distaste for the modern world (with its dreaded Internet and mobile phones) and his nostalgia for an older, simpler USA. Personally, I think the film is far more complex than that. It’s with the pesky phone that, after all, Earl pulls off one of his most brilliant outflanking manoeuvres; and it’s precisely the “family values” of suburban America that Earl has spent most of his life fleeing, in favour of the freedom of the open road. Yet the conundrum he must ultimately face is just as typically American: freedom is always relative, and (contrary to Kris Kristofferson’s famous song lyric) it’s often just another word for something left to lose. Where does Earl end up? I’m not telling, except to say that Eastwood sums it up the best way he knows how: in the delicate interplay between long shots and close shots, a landscape and a built environment, an old, weathered face and a sweet piece of music.

|

4 stars

|

★★★★

|

© Adrian Martin, March 2019

The Mule

Director: Clint Eastwood

US, 2018, 116 mins

Release date: January 24

Distributor: Roadshow

Rated: M

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: