No Longer Home is a semi-autobiographical narrative point-and-click game about two non-binary people in their early twenties. Developed by Humble Grove and published by Fellow Traveler, the game tells a domestic, nostalgic, and sometimes surreal tale about couple Ao and Bo, who are grappling with responsibility and stability as they graduate from university into the unstructured world of adulthood.

The story takes place as they pack up the home they have shared for the past two years. The couple feel they have failed in key ways to secure the kind of adult life that they expected: they are moving out of their London flat; they have struggled to find gainful employment. Consequently, Ao has decided to return to Japan, while Bo considers the reality that they may be unable to follow them – and moreover, they may not want to.

As the story unfolds, the pair question, both together and separately, what their plans for the future will hold, and how their economic and personal circumstances will affect their ability to build the lives they want. This coming-of-age narrative is set to an utterly haunting, intoxicating score by Eli Rainsberry that reverberated through my brain as I navigated Ao and Bo’s small home, and for a long time afterward.

The game can be played in an hour or two, maybe in bed, or in front of the heater, as Rainsberry’s remarkable, resonant score pulls you deeper into the story. Combined with a muted colour scheme of the low poly visuals, No Longer Home offers a gentle, narrative experience that left me wishing it had an autoplay feature that allowed me to sit back and let the dialogue wash over me, instead of fastidiously clicking through.

The point of view shifts between Ao and Bo as they walk around, planning a barbecue, or discussing their future plans. Their house, where the entire game takes place, is navigable through a point-and-click system that sees minimalist, Kentucky Route Zero-esque annotations arise over objects that are interactive – a particularly charming element of this is when you click to walk, and a small plant unfurls as the character approaches.

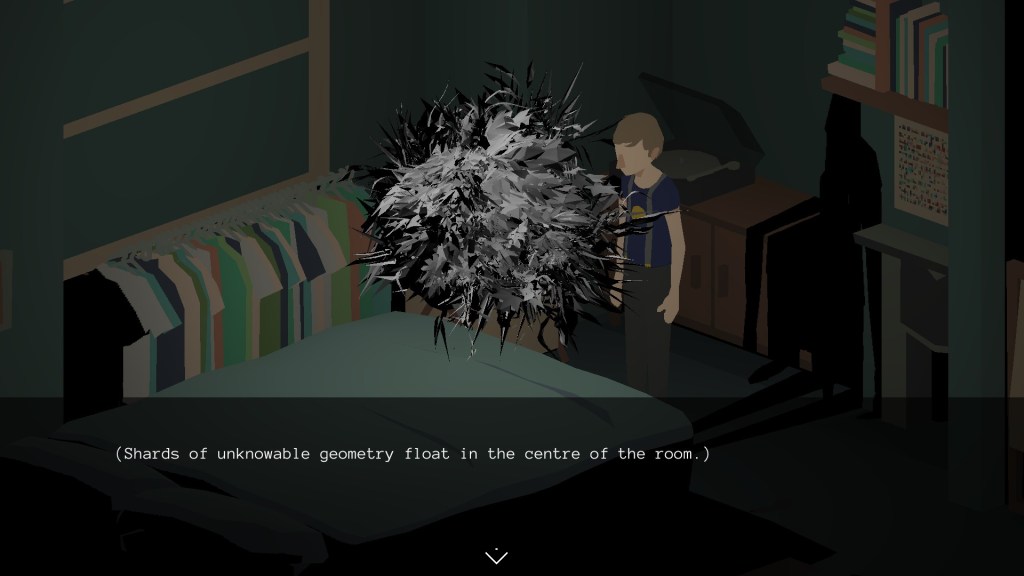

As these conversations play out, the environment around the characters reflects this transitional phase of their lives – their bedroom wall shifts back to reveal a full moon over a silhouetted house as they discuss gentrification, and earlier on, a garden shed from a past sharehouse reconstructs itself before the player’s eyes as the couple discusses former living arrangements with their friends. The sense of the transitory is embedded in the domestic environments of the game; what once felt stabl, and sturdy can now contract, expand and dissolve at a moment’s notice, replicating the dissociative anxiety that can accompany a major life change.

The influence of Kentucky Route Zero permeates every aspect of the game. It even adopts its magic-realist approach to a narrative that celebrates place, but Humble Grove doesn’t wholly make the genre their own. Some of the game’s more surreal aspects, like these shifting walls and boundaries, communicate something important about the characters’ relationships to space and security. Others feel more arbitrary. When Bo encounters a shifting, fractal orb above their bed, it feels more like a genre flourish than a narrative counterweight.

Ao and Bo also have explicable, concrete issues as a couple: Bo resents that Ao is messy, but finds it hard to articulate this. Ao, more outspoken than Bo, struggles with Bo’s indecisive nature, but similarly fails to address it directly. These traits are reflected in their characterful low poly designs: when left idle, Bo alleviates their poor posture with a gentle stretch, and Ao sits with a leg perennially drawn up to their chest.

While there are dialogue options that allow the player to interact with the narrative, No Longer Home doesn’t shy away from its linear design: it has a story to tell you, and you are along for the ride, which it relays through dialogue that mostly feels naturalistic.

However, conversations between Ao and Bo can feel self-conscious and a little posed at times: when discussing the gentrification of their London suburb, Bo laments the displacement of ‘poor people,’ a seemingly nebulous designation in their mind, and Ao is quick to point out that, as young university graduates, they number among the displacers more than the displaced. In conversations like these, the characters feel less like fully fleshed-out people, and more like mouthpieces for the values or anxieties of the developers – when conversation extends beyond their personal aims into the political realm, their dialogue could almost be interchangeable, which is compounded by a UI design that sometimes makes it hard to tell who is meant to be speaking.

This conversation culminates with Bo stating they ‘wish [they] had something more to offer than vague preaching,’ and frankly, so did I. Ultimately, this lack of self-awareness might just be true to the economic and social circumstances of the characters.

Bo, after four years of art school, has refused to get a part-time job, and Ao’s parents, one of whom is the advertising director of a prestigious firm, paid their university fees. The languid melancholy of their discussions of the future – which touch on identity versus expectation and artistic aspirations – is founded on the assumption that they have access to financial support through their families. It’s uncharitable to frame character flaws as a criticism of the game per se, but it was a consistent tension that felt strangely unexamined.

What are we meant to conclude of these characters? Is the statement of their class position intended to exonerate them from examining this position further? Is their complete financial security meant to be a sidenote in this story about how they will navigate the future? Ultimately, the game’s relationship with money felt evasive: defensive acknowledgement, then withdrawal. Who is paying Bo and Ao’s rent? Can you really tell a story about home that isn’t about money?

No Longer Home toes the line between a commercial and personal project in a way that makes it hard to critically assess. It’s a game that deals with a familiar form of melancholy with a delicate touch, but sometimes, this borders on insubstantial. The narrative, while personal, lacks substantial introspection.

It’s not a damning flaw: for lovers of gentle narrative games, No Longer Home will be a balm. Personally, I wish it had gone deeper. Given that the main characters’ economic and social circumstances are regularly, explicitly discussed, I would have liked the narrative to have confronted the way these circumstances shaped their reality more directly. I can see, though, that this kind of interrogation would be out of place in a game that is dreamlike and insular by design. After all, Ao and Bo don’t even want to leave the house.

Three stars ⭑⭑⭑

No Longer Home

Platforms: PC

Developer: Humble Grove

Publisher: Fellow Traveller

Release Date: 30 July 2021

A copy of No Longer Home was provided for the purposes of this review.

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: