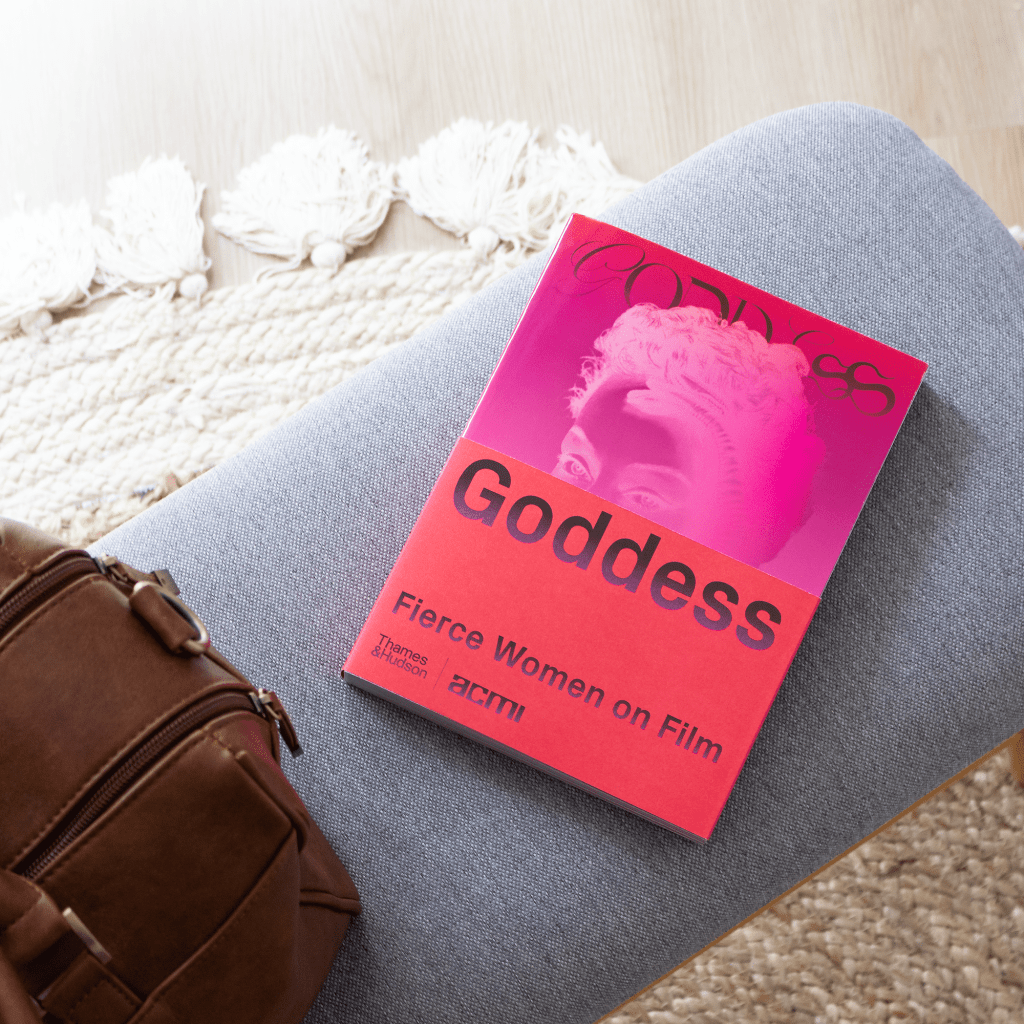

This edited extract, by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, was originally published in Goddess: Fierce Women on Film (2023). See the end of the article for details on the book and ACMI’s current Goddess exhibition.

Mother and Son was an Australian sitcom that ran on the ABC from 1984 to 1994, starring Ruth Cracknell and Garry McDonald as the eponymous parent and (adult) child. McDonald’s long-suffering Arthur would – episode in, episode out – care for Cracknell’s Maggie, a war widow experiencing the onset of dementia.

Her captivating, flawed, funny and very human portrayal of Maggie made Cracknell a national icon. The horror and tragedy of her loosening grip on reality was somehow always sensitively crafted into something that, while often funny, was also kind-hearted and real.

Read: Santilla Chingaipe for ACMI: ‘If we’re not careful, we can regress’

There are other portrayals of older women on the Australian screen that reject simplistic, two-dimensional representations. Wearing her signature, retro cat-eye glasses, Joyce Jacobs’ Esme Watson in A Country Practice (1981–1993) was a mean-spirited nosy parker who, over time, revealed a more complex and often generous personality.

More recently, the darker side of women aging formed the core of Natalie Erika James’s internationally acclaimed horror film Relic (2020), where the inescapable impact of a condition manifesting as dementia in Robyn Nevin’s Edna deeply impacted not only herself, but her daughter and granddaughter.

Read: Love Me star Heather Mitchell on playing women with agency

Hagsploitation!

These examples may feel oceans apart tonally, but they all hinge on older women who are deemed to be out of sync with the way the younger people in their worlds want them to be. There are, in both Mother and Son and Relic especially, regressions, slips and mental ellipses that utilise comedy and horror respectively to strikingly different ends.

In the space between horror and comedy are the roots of what has been variously called ‘hagsploitation’, ‘psychobiddy’ or even ‘grande dame guignol’ films – a popular subgenre of Hollywood movies that peaked in the 1960s and 1970s where one-time goddesses of the silver screen played often parodic ciphers of their star personae. Time has supposedly rendered them monstrous through their desperate refusal to let go of the past.

Typified by Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) starring Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, the ur-hagsploitation film remains Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) with Gloria Swanson. Swanson plays a fictionalised version of herself as a one-time silent-era screen queen, psychologically destroyed as her idealised vision of herself, which peaked during her professional heyday, goes through the inescapable process of ageing.

Enamoured with her youthful star image, the reality of growing old in an industry with no interest in women above a certain age destroys her, leading her to murder and a collapse into complete self-delusion.

Read: Geena Davis heads to Melbourne for ACMI: Goddess exhibition

Camp and chaos

Floating in that strange liminal space between horror and comedy, hagsploitation blasts its prerequisite components – tragedy, the grotesque, camp – at full volume. Whether it’s over-the-top performances, overwrought storylines, or just good old-fashioned chaos, in hagsploitation excess is the name of the game.

While the uninitiated might be uncomfortable with the falsely assumed demeaning nature of the term and its reference to lurid melodramas, the women playing these roles – and their undisguised delight in doing so – render these films electrifying. This was (and remains) an industry where once you reach the ripe old age of forty, work slowly starts to dry up.

The dearth of meaty, interesting roles for women is more often than not a career death knell; many women disappear, while a handful are reduced to insipid maternal cliches.

A lucky few, however, survive the ‘women ageing in Hollywood’ Hunger Games to land solid roles, but we can probably count them on our fingers: Helen Mirren, Judi Dench, Emma Thompson, Angela Bassett, Meryl Streep, Michelle Pfeiffer, Viola Davis … The list is impressive, but it’s far too short.

Looking back to the hagsploitation Ground Zero of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, both the film itself and the journeys of its two enigmatic stars reveal much about broader attitudes towards women and ageing on screen. The film follows the Hudson sisters, Jane (Davis) and Blanche (Crawford). Jane is an egomaniacal ex-child star whose career was overtaken by her more serious, down-to-earth sibling.

Now isolated and forgotten, her mental health spirals out of control, and the sickly, bedridden Blanche realises the danger she’s in at the hands of her abusive primary carer.

Drenched in hagsploitation’s signature outrageous camp spirit, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is a film about two women who lack power in the world precisely because of their age and gender. They have become invisible, poignantly rejecting the careers of both Crawford and Davis themselves. If Jane and Blanche faced the reality of being spat out by an industry that no longer needed them, it was an experience both Crawford and Davis knew only too well.

No country for old women

Beginning her screen career in the silent era, Crawford had already been granted a rare professional second chance decades earlier. Playing a dazzling array of femme fatales and gold diggers during the pre-Code era made Crawford a screen idol, but by the late 1930s her career was in decline.

MGM cancelled her contract after almost 20 years in 1943 but, moving to Warner Bros, she beat Davis for the title role of Michael Curtiz’s classic film noir Mildred Pierce in 1945, in a performance that garnered Crawford a Best Actress Oscar and resurrected her career.

Davis and Crawford were famously competitive when it came to Hollywood’s far-too-rare quality roles for women, and their careers followed similar (although not identical) paths. Beginning on stage and having a reputation as a serious actor rather than a typical ‘movie star’, Davis received five Best Actress Oscar nominations in a row from 1938 to 1942, winning in both 1935 and 1938.

In her forties, like Crawford, Davis found herself at a transitional point professionally between studio contracts, which led to one of her most memorable films, Joseph L Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950). Davis knew it would be professional dynamite for her, and it was, solidifying her superstar status in an industry otherwise obsessed with younger women – it featured a tiny early appearance by Marilyn Monroe – and facilitating Davis’s much-deserved comeback.

Despite the success of All About Eve and Mildred Pierce, in Hollywood’s eyes, Davis and Crawford still weren’t getting any younger; the former even contemptuously placed a ‘work wanted’ ad in Variety just before What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? premiered.

While hardly either woman’s most glamorous role, both knew the realities of the industry when it came to age and gender discrimination. Despite their complex and often fraught interpersonal relationship (documented in the 2017 miniseries Feud starring Jessica Lange and Susan Sarandon), with Baby Jane they struck gold again.

Nominated for five Oscars (including one for Davis as Best Actress, another source of contention between the women), What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? kickstarted their careers once more, and gave birth – for better or for worse – to the dazzling, hysterical, hilariously dark world of hagsploitation.

Beyond What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, hagsploitation endured in large part thanks to a queer filmmaker with a background in experimental filmmaking, whose contemporaries included Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger. It was under Curtis Harrington’s direction that hagsploitaiton truly embraced its wide-eyed, half-crazed delights, boosting the careers of one-time classic-era giants like Debbie Reynolds and Shelley Winters in films including What’s the Matter with Helen? (1971) and Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (1972).

Crawford and Davis continued to work in the subgenre, Davis co-starring with Olivia de Havilland in Aldrich’s Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte in 1964 (the latter replacing Crawford who dropped out, unable to work with Davis again), and playing twins – one good, one evil – that same year in the brilliant Dead Ringer, directed by Paul Henreid.

Crawford continued her hagsploitation work in 1964 in trashmaster extraordinaire William Castle’s Strait-Jacket, and in Jim O’Connolly’s Berserk! (1967).

Hag magic

Hagsploitation endures in films like Misery (1990), Flowers in the Attic (1987), Hereditary (2018) and Greta (2018), but through What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? it remains linked to the 60s and 70s, where it resurrected the careers of real-life movie stars who had been unfairly excluded from the industry because of discrimination.

The very word ‘hagsploitation’ may, for some, feel intrinsically misogynistic, but this ignores how enormously empowering these films were for women like Davis and Crawford, gaining them employment in an industry that had otherwise rejected them because they were considered past their use-by date.

These women embraced the ironic force of the ‘hag’ to boost their careers at a time in their lives when they were otherwise told they were no longer needed. Davis’s final feature film role was horror maestro Larry Cohen’s 1989 horror-comedy Wicked Stepmother, while Crawford’s swan song was in Freddie Francis’s monster movie Trog in 1970.

Liberation hides in strange places, and hagsploitation is a reminder that if you embrace the very thing that has seen you pushed to the margins hard enough, a special magic can be squeezed out that can shock and sparkle in equal measure on movie screens forever.

Goddess: Fierce Women on Screen is available to buy from the ACMI store or online. ACMI’s world-premiere Goddess: Power, Glamour, Rebellion exhibition is open now. Find out more.