One week ago, Melbourne-based studio Route 59 Games released their debut title, Necrobarista, to critical and popular acclaim. A darkly funny, aesthetically sumptuous visual novel, Necrobarista charts a night in The Terminal, a Melbourne coffee shop where the dead spend their last day on earth. Set to a juggernaut soundtrack from Kevin Penkin, a BAFTA-nominated composer who also worked on Melbourne title Florence (my partner described the soundtrack as being ‘like getting a massage from your former self’; make of this what you will), the narrative winds deftly between humour and pathos. It’s also populated by distinctly Australian characters, slang, idioms and all, in an environment (stunningly rendered by an art team lead by Ngoc Vu) that feels quintessentially Melbourne.

Lead developer Kevin (Hsun-Yu) Chen told me that even the studio itself was named after the 59 tramline, the line that the developers took to work. The game’s glorious familiarity comes not just from its depiction of Melbourne, but because it is shaped by the city, in the same way I am. For me, the game couldn’t have come at a better time.

When Melbourne entered stage three restrictions in March, I felt pure panic. We are now three weeks into a second lockdown, and I’m habituated to my new life of Zoom birthdays, working from home, masks, and hand sanitiser. Instead of panic, I just feel homesick. This city is the first home I chose, and in the decade I have lived here, I feel like Melbourne has chosen me back. From ritualistic happy hour reds at The Moat before festival events, and magics at Seven Seeds, to Cheap Monday at Cinema Nova and sit-ins at Parliament House, there’s a ritual to the life I’ve built for myself, to the person that I’ve grown into, that feels inextricable from this city.

But playing Necrobarista, I found, unexpectedly, that this homesickness started to abate. It hit me around the time that Ned Kelly offered one of the recently departed ‘a durry’ (it’s narrative designer Damon Reece’s favourite line for good reason) that this all felt familiar: The Terminal’s dark wood interior, indoor plants, sarcastic barista, and population of coffee drinkers whose attachment to the mortal plane is questionable at best, all feel like home.

ned kelly asking “You want a durry?” is perhaps one of my favourite lines in the whole game https://t.co/5VAoeRxqdA

— damon (@demanrisu) July 29, 2020

With this in mind, I began to think of other Victorian games that would let me experience my home state, and the city I miss so much. While we’re all doing our part to stay home and minimise the risk of community transmission, these digital experiences are a salve. Each of these offers the opportunity to relive a different aspect of Victoria, whether it’s the gentle sway of commuters on a tram, the song of native birds, the click of a traffic light, or sass from a goth barista who makes you a coffee strong enough to wake the dead. This one goes out to Victorians in lockdown who are missing their state, and anyone else who wants to touch Melbourne from afar.

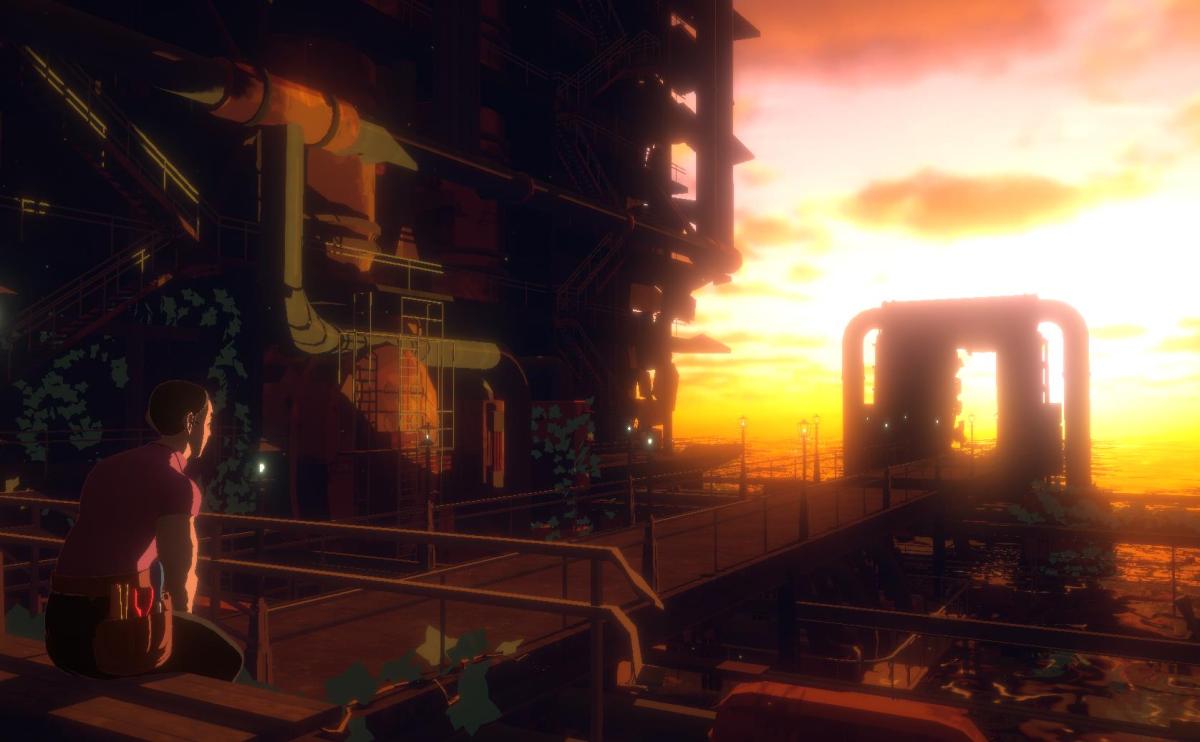

A SHORT TRIP, ALEXANDER PERRIN

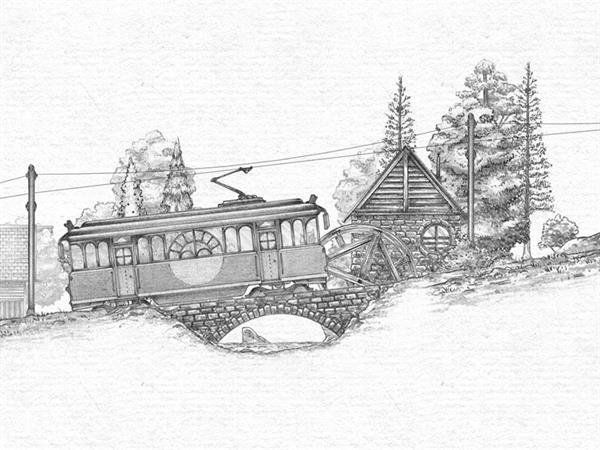

Perrin’s ‘A Short Trip’ showcases his incredibly eye for detail.

A Short Trip is a tiny browser game with a simple premise: you are driving a tram through town, stopping to pick up and drop off passengers on the way. Made by Alexander Perrin, and rendered meticulously in graphite pencil, the game makes high art out of the grind of commuting. During development, Perrin focussed on recreating sensory details; he even sourced and recorded an antique tram bell, for the game’s tram bell.

So you know when your mate @Tezamondo ‘s mate has an antique tram bell that you can just use to record antique tram bell sounds 🚃🔔 pic.twitter.com/KHYFbAfgf3

— Alexander Perrin (@alexanderperrin) August 5, 2017

While the setting is magical – the passengers you pick up are not Melbourne commuters but little cat people, and your tramline travels the length of a mountain town – the sound and movement of the tram that it feels instantly familiar.

Another aspect that will feel intimate to any tram commuters is what Perrin terms the ‘passenger sway physics’ of the game: the movement of the passengers inside the tram is affected by the tram’s acceleration, so they jostle and wobble as the tram starts and stops. He tells me, ‘I always found it amusing when riding Melbourne trams to see everyone sway back and forth in graceful unison. It’s particularly great in the mornings when everyone looks a little sleepy or meh, but having to unwillingly partake in this perfectly synchronised wobble dance.’

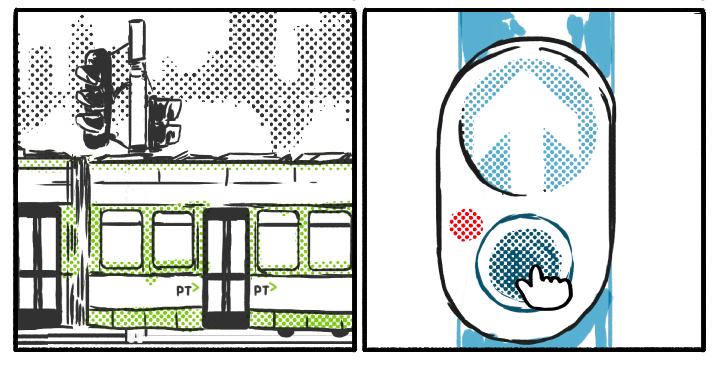

Touch Melbourne, Andrew Gleeson and Cecile Richard

Touch Melbourne celebrates the every day; it’s a sentiment feels particularly moving now.

Touch Melbourne is a tiny, first person game that details the experience of hanging out in a city, told through the senses. Rather than being driven by dialogue or plot, this story is structured around minute gestures and sensory experiences that bring the city to life around you.

When they created the game, Richard had just moved to Australia, and Gleeson drew on the homesickness he felt during the year he spent living in Europe. This sense of experience Melbourne with fresh eyes is palpable; from a Myki card that takes a couple of taps to touch on successfully, to the familiar hollow click of a pedestrian crossing button, it’s a paean to details that might evade the more jaded, less observant creator.

Recreating the soundscape of the city was particularly important to them – but the bustling reality of the city proved something of an obstacle to taking a crisp field recording. Gleeson found an unexpected workaround:

‘For the clunky pedestrian button noise, I went and got audio for myself by walking up and down Sydney Rd on a quiet night, since I was so passionate about it sounding right in the game.’

The game’s simple, intimate narrative feels both deeply personal, and totally relatable; it makes sense that the game was developed in the early stages of a relationship. Richard says, ‘We were maybe dating for a month or so when we made it, and I think that a lot of the cosiness of the game stems from that wide-eyed, butterflies-in-the-stomach feeling.’

If you’re feeling a little cooped up in an apartment or inner city spot, you can experience the beauty of the Gippsland bush with Paperbark. This stunning digital storybook allows players of any ages to direct a wombat to collect bugs and scramble under logs. As you explore, a story unfolds, narrated by Camp Cope lead singer Georgia Maq. The game unfolds with beautiful watercolour-inspired visuals and a soundscape full of bird song; playable on iOS and Android, it’s also perfect for someone unfamiliar with games, due to its gentle pace, and intuitive touch controls.

While Paperbark is radically different from Necrobarista in terms of style, the two games do have one thing in common: they deal with difficult topics in an even-handed way. Where Necrobarista deals with mortality, Paperbark tells a story of bushfire.The narrative is thoughtful and accessible; a beautiful meditation on the reality of the Australian bush for an adult, and a good way to start a conversation with a child.

The wombat might be the star of Paperbark now, but lead developer Terry Burdak tells me that the team originally planned a more complex ecosystem: ‘originally Paperbark was designed to be about a wombat AND a sugar glider — for the first part of development, both were fully implemented in the game. They had two parallel stories told from their own perspective of the same events; the sugar glider would jump around the trees at night chasing moths, and then the following day you’d play as the wombat.’

Ultimately, it proved too complicated, and the team focussed on the wombat’s story. The sugar glider isn’t completely gone, however; they kept them in the key art on the website.

The sugar glider, still celebrated in Paperbark’s key art.

Pet the pigeons, pick up the pigeons, write about them in your notebook!

Pigeon Game is a gorgeous little experience where you walk around a park interacting with pigeons and writing about them in your journal. Getting to know the squashy, characterful little birds is heaps of fun for people of any age. In fact, developer Leura Smith knew she was onto a good thing when she realised her mum enjoyed playing an early version of the game: ‘It felt a bit rare and important, that I was able to make something that she felt comfortable playing. A lot of my design decisions for the game ended up being based around how she interacted with the game, and she really liked the jiggle of the pigeons.’

There’s a funny secret to the jiggly pigeons, too. The wonderful wobbly birds of this gentle game were originally inspired by… boobs! Smith explains, ‘ When I was first thinking of the game, I was thinking a lot about the physicality of pigeons, and I remember joking that they kinda remind me of the boobs from Dead or Alive: Xtreme Beach Volleyball [NB: in that game, boobs are not hard to come by]. When I first made the game it was a bit of a big joke, throwaway game, so I thought it would be funny to just make the birds based off dead or alive boobies.’

After a resoundingly positive reception these soft, spherical pigeons, the boobie physics stayed. Smith considers this a particular achievement of the game: ‘I think there’s something pretty funny about using boob physics – a thing developed for the fantasy of men – to create my innocent little game for my mum to play.’

Terracotta, Olivia Haines

The pastel world Olivia Haines’ creates is inviting and dreamlike.

The latest game from 3d artist and game developer Olivia Haines, Terracotta is powerful in its simplicity. Terracotta presents a cityscape, rendered in dreamlike pinks and pastels, and within it, the player is given a first-person perspective on the main character’s walk around the city. As you walk, you experience the character’s thoughts as text on the screen, as they ruminate on their experience with depression. Rather than a sustained narrative, you are given an intimate insight into the experience of the main character, her mental state, and how she processes and copes with the world around her.

Like her previous game, Dollhouse, it showcases her gift for creating art that feels intimate and real without being overwhelming. In fact, Terracotta feels remarkably expansive, and it’s easy to believe that the world, though inaccessible to the player, extends far beyond the bounds of the game. An entirely relatable feeling in current times, but instead of being upsetting, it was a relief to feel understood, and to see a shape given to feelings I’ve had too. And isn’t that one of the most beautiful things that art is capable of doing? Making us feel more explicable, and less alone?