In season 2 of the American romantic comedy-drama Jane The Virgin, aspiring romance novelist and titular virgin Jane Villanueva (Gina Rodriguez) is in a bit of a pickle. After once again switching supervisors in her masters program, she is desperate to make things work with her third advisor, Marlene Donaldson (Melanie Mayron), who – in appearance – looks like the result of searching for ‘second-wave feminism’ on a stock photo website, and who has nothing but contempt for the romance genre.

Marlene sets Jane a challenge: make sure her manuscript passes the Bechdel Test – meaning that the story should have at least two female characters, they need to talk to each other, and the conversation should be about something other than a man.

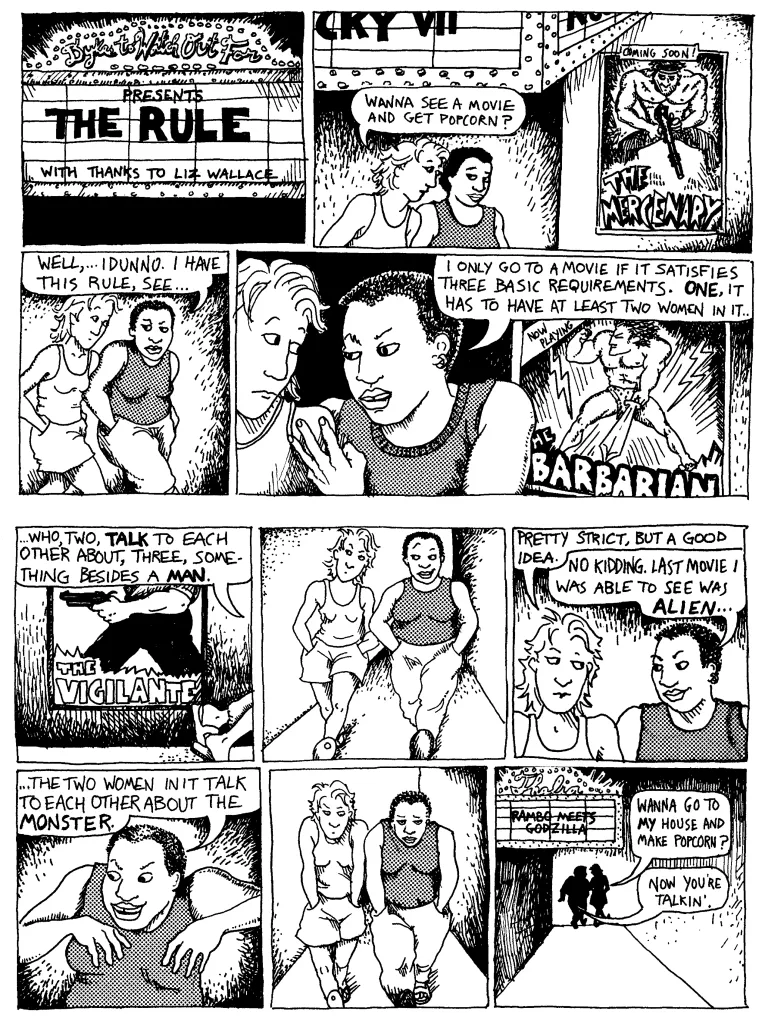

The Bechdel Test is less a seal of feminist approval, and more of an exercise in examining and quantifying trends in representation. The test comes from The Rule, a 1985 comic that appeared in Alison Bechdel’s comic strip Dykes To Watch Out For.

In that comic, one friend suggests seeing a movie, and the other expresses frustration at how many movies depict women as nothing but accessories to the male protagonist’s character arc. She reveals that she will only see movies that meet a certain set of standards, and these standards have since been immortalised as the Bechdel Test.

From its humble beginnings as a joke in a comic strip to its status as an obstacle in a comedy series, it’s clear the Bechdel Test has reached a level of mainstream saturation. But is it still relevant? Or is it less exciting now that everyone’s heard of it?

Google search trends suggest that the test has been declining in relevance ever since a peak in 2017.

The Bechdel Test Movie List is a website that applies the test to every major film release on a pass-fail basis, marking each film with either a green tick or red cross. Scrolling through the website does offer some encouraging trends, with the proportion of green ticks increasing over the last 15 years.

It is also worth noting that a film passing or failing the Bechdel Test says little about the roles women play in the narrative.

Scary Robots

Scary Movie 3 (2003), which dances on the line between parodying and reinforcing horror’s often not-great attitude toward women, passes the Bechdel Test in the opening scene when two named dumb blonde stereotypes, Becca (Pamela Anderson) and Katie (Jenny McCarthy-Wahlberg), fail to complete a crossword. I’m cheating a little, as a man’s name is brought up, but his role in the conversation is so negligible that he may as well not exist (sorry, ‘Josh’, nobody cares about you).

On the other hand, Pacific Rim (2013), a film about giant robots fighting giant sea monsters, fails the Bechdel Test but gives us a terrific female character in the form of Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi).

Robots and sea monsters aside, Pacific Rim is primarily a film about grief. Once Mako is introduced, the plot is less about the apparent protagonist Raleigh (Charlie Hunnam) moving on from his brother’s death, and more about Mako avenging her family.

Director Guillermo Del Toro revealed that if he had been able to direct the sequel, it would have been the Mako Mori show from the beginning, but sadly it was not to be.

As Marlene points out at the end of that Jane The Virgin episode, the test is just a baseline, not comprehensive outline of a story’s feminist merits. Really, the point of the test is how often it’s failed. The bar has been raised all the way to ankle height, yet so many filmmakers trip over it.

The test has also inspired derivatives, such as the Sexy Lamp Test. Comic writer Kelly Sue DeConnnick proposed this test after reading so many scripts in which the plot would still hang together if the female lead was replaced with one of those lamps that looks like a pair of legs.

Consider the Taken series (2008, 2012, 2014), which follows one man’s inability to prevent his daughter from being, well, taken. The daughter in question has so little agency or personality that she may as well be a lamp, sexy or otherwise.

Other tests have been proposed to make up for the unintentional limitations of the Bechdel Test. Even if the bar is set deliberately low, it only describes one way in which on-screen representation is lacking, and ignores factors such as race, class, sexuality, gender identity, or disability.

Vito Russo

The LGBT activist organisation GLAAD proposed the Vito Russo test, named for the author of the 1981 book The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. It asks whether a film’s LGBT characters, if it has any, are predominantly defined by factors other than their gender identity or sexuality, and whether removing them would have a significant effect on the plot.

In 2018, researchers Sadia Habib and Shaf Choudry came up with the Riz Test, named after actor Riz Ahmed, to quantify onscreen Muslim representation. This test looks at stereotypes around Muslim characters, who are often depicted as perpetrators or victims of terrorism, as being culturally backward or superstitiously anti-modern, and as enforcing rigidly patriarchal family structures.

To my mind, if any test is relevant at all anymore, it is as the start of a much longer and more interesting conversation.

If Roger Ebert was right, and movies are ‘a machine that generates empathy’, then the people we’re asked to empathise with are overwhelmingly, if not exclusively, male and pale.

What any of these tests – whether Bechdel, Riz, Vito Russo, or Sexy Lamp – are showing us is that so many filmmakers fall into the same patterns, and that audiences can, and should, continue to demand better.