When Michael Bentham’s debut feature film Disclosure screens to a real (not virtual) sold out Australian audience at the CinefestOz Film Festival in WA this weekend, it will be yet another triumph for a small film with a complex history. Stuck in locked down Melbourne, the writer-director won’t be traveling to accompany his film in the south west, but he’s still grateful to have it shown on a big screen at all during these trying times.

Made entirely without agency support, the fully independent micro budget film, produced by Donna Lyon, was a surprise hit when it premiered to rave reviews and packed out audiences at the Palm Springs Film Festival in January. Huffpost film critic Brad Schreiber placed it in his top-10 highlights of the festival and described it as ‘disturbing in the best possible way.’ This was just one of many raves. US distributor Breaking Glass Films acquired it for theatrical distribution at the Berlinale, but then, as Bentham says on the phone to Screenhub, ‘we got COVID-ed!’

The film went online in the US in July. Locally, it’s just been picked up by ANZ distributor Bonsai Films, who are planning to screen it in theatres, though on paper it could be a tricky one to sell.

A taut four-hander set in one location on a picturesque property in the Dandenong ranges, Disclosure takes place over one afternoon as two sets of parents struggle to deal with the fact that one of their children, a four-year-old girl, has accused another one, a 9-year-old boy, of abusing her. Child on child sex abuse is a growing issue, particularly in western societies, and the film draws on extensive research around this.

Read: Australian lineup for Palm Springs 2020

But rest assured, there’s hardly a child to be seen on screen. This story is all about the parents and the ways their friendly, cooperative stance disintegrates as the day wears on. Judgements about each other’s parenting choices, sexuality and careers come into play. It’s a story that will resonate with anyone who’s ever navigated the fraught playground of parental politics.

The four actors (Geraldine Hakewell, Tom Wren, Mark Leonard Winter and Matilda Ridgway) are superb, delivering nuanced performances in very long takes, and as Bentham says, this was one of the keys to keeping the budget contained and the shoot time confined to a breakneck two-week period in early 2018.

Coming from the UK, Bentham is married to an Australian and they moved to Melbourne about six years ago. A graduate of the UK’s National Film and Television School, his career has taken in film, television and music, including directing Channel 4-commissioned documentary Chatham Jack as well as teaching.

In this interview Bentham talked to Screenhub about the inspiration for his boundary-pushing story, his risky strategy for keeping costs down, and the wild card luck of being selected by Jane Schoettle for Palm Springs.

Where did you get the idea for the story?

It comes from two places. It was inspired by real events, and also from research. I first came across the subject matter when some close friends confided in me that their child had made a disclosure about being abused by another older child. And at the time I remember thinking that it was some weird anomalous event. But a cursory search on the internet revealed that this was actually a very significant and growing problem, certainly across the developed world.

One element that came out of the research was a pattern that was identified in a large kind of meta analysis done by the late Professor Freda Briggs in South Australia, and was part of a submission she made for the Inquiry into the harm being done to Australian children through access to pornography on the internet. The pattern she identified was that such a disclosure, particularly in remoter communities, often led to the family who made the original allegation being driven out of their community by the family of the perpetrator. These disclosures led to witch hunts, basically, which I found horrifying. But as a storyteller and a filmmaker this is fascinating to me.

‘I wanted to explore this really toxic dynamic, through constructing a cinematic narrative, and ultimately to raise the public profile of this problem.’

Michael Bentham

And to also promote the kinds of recommendations that people like Freda Briggs and others have made to various royal commissions and I think are largely falling on deaf ears.

Children’s play, like ‘doctors and nurses’ can often become sexual. Where is the line between play and child on child abuse?

Consent is a major theme that I explore in the film, and this is why I have two of the adult characters – the parents of the child who makes the disclosure – being very expressive in their sexuality. This was really to flag this notion of consent. Some conservative people might find it confronting, but crucially they are operating in a consensual space, and that’s to contrast with the non-consensual space that acts of abuse take place. Doctors and nurses is kind of a playful consensual space.

But it’s important to note that our film is actually not about that child on child backstory. It’s about how the parents respond to that event, and to the disclosure.

Did the story change much from first to final draft?

It was pretty quick. The original draft took a matter of weeks. The character who went through the biggest development was Bek (Geraldine Hakewell) – the mother of the accused. At some point I decided to make her a survivor. The way I had originally conceived her she was becoming a bit of a straw person who was just basically antagonistic. I wanted to find a way of empathizing with her. The idea is that she’s buried her trauma in years of denial so the impact of her son being accused of being a perpetrator is really catastrophic to her. And in doing so she becomes a much more rounded and empathetic character.

What was the timeline of the project?

The initial idea came around 2017. The script came quickly. I sent it to Donna and she was really moved by it and wanted to do it. It is a very contained piece, with four adults in one location, so logistically it wasn’t a massive challenge to put together.

We shot the film in beginning of 2018. Then there was a delay because we were hoping to draw down finance for the sound design but that didn’t come through. So I ended up calling contacts of mine in the UK and we ended up serendipitously getting an amazing deal with an incubator company that was attached to the National Film and Television School in the UK. And Odinn Ingibergsson and Sean McGarrity were the sound designers who did an extraordinary job. But because of that delay we didn’t end up doing sound design until a year later in Jan 2019. And we got a final mix in middle of 2019 and then had our premiere at Palm Springs in January 2020.

How did this external sound design process happen?

It physically took place in the UK and I got on a plane and went to work with those guys. Odinn is a Danish sound designer and Sean is Irish. That was fascinating in terms of what happens in that collaborative space. I basically brought to them this Australian story, and neither of them have been to Australia. I’d brought with me all these sounds from Australia and it was very interesting to see their reactions. For instance, because it’s set in a relatively rural area there is all this birdsong and one of the featured birds is the kookaburra. And they’d never heard anything like it. They thought it was a monkey!

It was really interesting for them to bring their world of experience and knowledge of sound and soundscapes coming from a different place, and especially into the more subjective parts of the soundtrack where they really take the viewer into a more internalized emotional space.

What were the practical and aesthetic decisions you made to contain the budget?

It was a really short shoot. It was ridiculous – like around 16 days. We made a really important aesthetic decision in the way we shot it. A lot of low budget films attempt to shoot in a very traditional way – with Master shots, mid shots, closeups. That requires multiple set-ups. And when you’re under that kind of time pressure, and you’ve got a lot of inexperienced crew – we had quite a few students on our crew – with the best will in the world you’re simply not going to be able to deliver the high production look and quality of a big budget movie. So what happens with a lot of low budget movies is that they attempt traditional coverage, but end up with something that looks more like daytime TV. I wanted to avoid that at all costs.

We decided to take a big risk in the way we shot the film, which was to shoot these very long extended developing shots. It’s risky because by doing it more traditionally you have lots of options in the edit – you can chop things out if a scene starts to dip in energy, or you can make it work in the edit.

But if you’re shooting a single locked off shot you’ve got nowhere to cut to. The scene has to work within that shot. That was the risk, that we wouldn’t be able to pull it off. The payoff was that if we did pull it off, that approach to covering this particular story perfectly worked with the nature of the film.

One comparison, or one of the inspirations, was Ruben Ostlund’s Force Majeure, a film that uses very long shots. Some of them are held for such a long time that the frame almost disintegrates. What’s extraordianary about that is it creates extraordinary dramatic tension. But it’s risky because you’ve got to have performances that hold together, and technical issues that hold together. But if it it works we could actually cover lots of material very quickly.

One of the things that really helped was the extraordinary cast who have all had a lot of theatre experience. This was absolutely crucial. They were used to delivering in one take these long arcs where their performances really cook over a long period of time. They just kept delivering and that made it all possible.

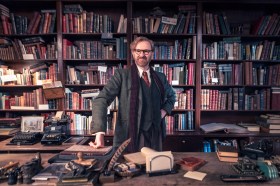

Michael Bentham on location. Supplied.

What was the biggest challenge?

There were technical challenges with the final set piece around the swimming pool, which is an incredibly slow tracking shot that gradually pushes in and puts the characters under more and more pressure. We started losing light and it was very complex in terms of choreography for the actors moving around the pool. I had a moment where I I thought we were going to crash and burn on that shot. The actors were getting really fried. We had one more go and the gods smiled on us.

How did you find your location?

It’s somewhere I’m really familiar with and so I wrote for that location, knowing there was a creek on the property and a huge fallen tree, and so we wouldn’t need to create that. I remember an exercise we did in film school which was called a Landscape Exercise where you went to a location, spent time there, and then had to make a story to fit in it. It was nice to know this space and bring it into the scripting.

How did you come to be teaching at the VCA?

When I was in the UK I had a tenured post for a while as the head of directing at the Northern Film School at Leeds, and also senior lecturer in screenwriting, so I’ve had a lot of experience mentoring screenwriters. I came over to Australia and landed in Melbourne and started cold calling for work. I’m relatively new in Australia so I didn’t have the contacts in the industry. I spoke to Nicolette Freeman who was then head of school at the VCA and she introduced me to the various heads of department and so I’ve had pretty regular teaching work ever since. I’ve also taught at other institutions, media practise at RMIT and at Monash, but my main work has come from the VCA.

Do you notice any differences in the teaching or culture of studying filmmaking here?

Not really, I think it translates across very well. The main thrust of my teaching methodology or pedagogy, if you like, is to recreate authentic environments in which the students make stuff, that’s how I learned. That’s what I enjoyed as a post grad student, and for my money that’s what really works in that teaching space. I’m a big one for delivering teaching through workshops and when I arrived here that seemed to be one of the key ways of delivering film teaching at the VCA.

The University of Melbourne is a very high ranking university so that VCA cohort is coming from a fairly traditional high achieving academic background, and it’s a very small cohort of maybe 15 students a year. Whereas at Leeds it’s something like 200. But Leeds Beckett is a relatively low ranking university and tends to draw locally, so students are from a much more mixed background with less traditional academic roots. That’s interesting and presents its own challenges.

How was your film selected for Palm Springs?

We were incredibly fortunate our film was spotted by Jane Schoettle, senior programmer at Palm Springs, and before that until recently she was senior programmer at Toronto. We really do have to thank Jane for her curiosity that went, ‘What’s this funny little film over here? Let’s have a look at it.’

She had the validated films coming from Australia, like Rodd Rathjen’s Buoyancy, Babyteeth, those films would have been presented to her as having the official stamp of approval. But Jane has that reputation of really wanting to find what she calls those hidden gems.

At that time we were cold-submitting to film festivals, which is a really thankless task, because there are so many small budget digital films being made that it’s more like a lottery.

She said that she just happened to notice the title of our film coming up on some list and asked what it was and wanted to see it. She said she thought the film was extraordinary and wanted it at Palm Springs, and predicted it would land really well in a North American audience. And that’s exactly what happened. We had three screenings. The first one we had reviews to die for, and the final screening there was word of mouth and was so oversubscribed they had to play it on two screens, which was fabulously affirming. As a result it got snapped up by a North American distributor, and then got a further huge long string of stellar reviews.

How has COVID affected you?

It’s been a a nightmare for us. It’s difficult enough getting a fully independent indie feature seen at all without having a global pandemic to content with.

After Palm Springs, the idea was to build the profile of the film through festivals, with a view of having an autumnal theatrical release. Instead because of Covid it went straight to DVD and VOD release in July, and because of that we didn’t get print reviews, and I think there’s clear evidence we haven’t reached our primary target audience in the US which is a real disappointment.

But to counter that, we have had some great reviews and just secured this awesome ANZ distributor Bonsai Films, and Jonathan Page is intent on putting together a theatrical release in Australia when theatres open. Obviously we would have loved to open in Australia on home territory in Victoria. But we’ve got an awful lot to be thankful and happy about. If we’d premiered a few months later than we did, we would have been sunk.

Read: Born to Be: gender, hope and a musical surgeon

Who is your audience?

I’d say it’s kind of older, an audience that might have had the experience of having children. It really gets under the skin of people who have families. We’re especially looking at women who are 30 or 40plus. In our discussions with distributors there hasn’t been a consistent feeling about if we should really flag the back issue, or if we just present it as a taut drama.One of my favourite genres is the thriller, and so in many of the ways it’s structured and builds tension in such a way that it should be a really compelling film to watch, and that child on child issue can be just a back story.

What’s your next project?

I can’t say too much about it, but all going well it will be a thriller with some horror notes. Again it will explore some serious contemporary themes, this time around rationality, faith and dogmatism, which are really writ large in society at the moment.

Disclosure screens at CinefestOz as part of the Official Selection on Friday 28 August at 8.30pm at the Orana Cinema in Busselton.

For more information about Disclosure and the issues it raises, visit the website.