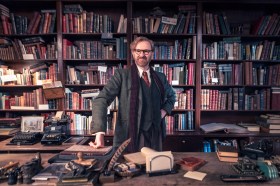

It’s not the machine, its the people. Image: working with Blackmagic systems on Hyperlight, a short by Nguyen Anh Nguyen, written by Nicolas Billon, and shot by Simran Dewan.

Anyone who can grow a company in seventeen years from an industrial site in Port Melbourne to an international company with an annual turnover of around $300m, using its own capital resources, is worth listening to.

Blackmagic Design is a name which is known across the wider Australian screen sector as a line of cameras which are remarkably cheap and find a place even in very high end productions. The company also makes a huge variety of technical equipment, while its DaVinci Resolve colour correcting software is an industry leader and very widely used.

A poor kid in a country town

Blackmagic was started by CEO Grant Petty whose methods and philosophy make sense when you know his history. Now in his mid forties, he was born in a beachside holiday town north of Sydney, until his family moved to Numurkah, a small country town in northern Victoria. His parents loved it but he was a beach kid. Even today he likes the sand when it is full of people, because he is fascinated by their energy and chaos.

In Numurkah, he explained, ‘The people were interesting because I noticed the class system. We lived in government housing and we were poor so we were just scum. People used to say get back to the Housing Commission where you belong.

‘It’s like, well you know, geez that’s pretty full on. I realised there’s a lot of people hold other people down as a way of making themselves feel important. If you’re creative I think you’ll see a very different philosophy in life.’

He described himself as ‘not confident and nerdilly kind of looking at things and working out how things worked.’ One of those things was an Apple 2 computer, lying around as part of a government resource program for struggling schools.

‘When I touched that Apple 2 I realised I wasn’t in that country town any more. I was gone. I was immediately transformed.

A sense of mission

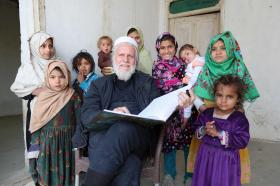

‘And I think can we make products and do the same thing to some kid in Indonesia, or some islands somewhere, or working in Los Angeles but can’t get into the industry. You can grab a camera and just do it, you can just get going, you can just do it yourself. I’m always thinking about the young kids, I’m always thinking about myself in the government housing with no money with the Salvation Army bringing a food package around for us, being told to get back to the Housing Commission where I belong. I think how do I reach out to that guy?

‘That’s the thing. If you can do that, you’ve actually contributed something otherwise you’re just managing market segments. You’re just another dickhead looking for a profit centre. If you can empower someone that’s a whole different thing.’

As part of that same government program the school had a rudimentary television studio. Petty got into it with a few friends, made it work and started to make programs. Ultimately he turned that passion into a career working in post production in the broadcast television sector. But it became increasingly uncomfortable.

‘When I got in the industry, the thing that struck me was that a lot of people were in it for a lifestyle. They don’t seem to really love it, you know. You had people who were more computer operators than they were creative, using things that were pretty cool and people were at each other’s throats and it was just a dog eat dog type of world.’

Power was concentrated at the top, opinions were silenced and nothing was ever really fixed. What is more, people were sidelined because they were creative.

In this desert he asked himself a life-changing question. How could he help creative people actually use the technology creatively? ‘They’ve got stories to tell or styles and imagery that they want to explore. How do you foster that? And I realised the best way to deal with this is to make the equipment low cost.’

Exploding the cost barrier

He started to work on the ferociously expensive post production sector, in which the cost of editing systems sucked imagination out of the ecosystem.

‘I thought I know what I need to do – I need to use computers properly. A lot of big dedicated systems are buying a computer and selling it for a lot of money, but actually you can just make a simple peripheral card that digests the video to the highest video standards you can get, plug that into the computer and people will develop and use software that will make a huge difference to the industry.’

The design work was a scramble because everything was changing anyway – Steve Jobs was reinvigorating Apple, slots and connectors were evolving, and HD was on the horizon. From a single peripheral card between cameras and computers providing the first profits, the inventory spread to a range of handy gadgets that kept prices tumbling and access increasing.

Really Blackmagic was exploiting and creating the huge transformation from mainframe to PC in the post sector.

‘We had to get our systems and our processes better as well. We had to be better as a company. But once we got to a certain point then we felt like okay, what is the next step that we need to be sorting out?’

He had a warchest, and returning from the scramble of growth to his fundamental question, and those kids who need access. At that moment, the Global Financial Crisis hit, and Blackmagic was one of the few technical companies which kept growing.

A wave of panic hit the post production sector because da Vinci was in trouble. The system sat at the core of post production; mostly around colour grading and correction, the arcane processes by which the images seem to be seamless, and provide artistic control. The process was managed by a priesthood which was really, really into colour and the way their decisions depended on and rippled through complex processes.

David takes over Goliath

Who could save da Vinci? What would happen if it vaporised? From the shadows came a small Australian company with a headlock on tricksy, useful gadgets.

‘If we could get da Vinci, and lower the cost of it, that would revolutionise the way things look. And, so we bought the company.’

I asked Petty about the consternation in the industry. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘We were a lot bigger than we looked. We just hid it.’ The first thing he did was changed the name to DaVinci.

‘It was a tough job turning it around but what we really wanted to do was try and bring colour correction into everything because colour correction’s the emotion track. We’ve got audio and video but the emotion of the shot is the color correction and the style. So we come up with the thousand dollar Mac version and then we come up actually even with the free version.

‘And it was all to drive that option of colour correction as an art form, a career people can choose, as a creative style and as something that contributes to the end result of a program or movie.’

Read more: Blackmagic consumes DaVinci, our account at the time.

As the capacity to do colour grading spread to small editing suites and suitcase companies, the big post-production houses were in trouble. That story has its own intricate history, with many different points of view. As far as Petty is concerned, the companies that were basically renting large scale computer systems to do small scale jobs disapppeared, and the survivors work on specialist high budget projects, which are very complex and require sophisticated levels of organisation.

What about the priesthood of colourists?

‘There’s nothing superhuman. Those guys are experienced but you’ve got 17-year old kids doing just as good a quality work. Just because the big post houses have got marketing dollars to promote their big guy doesn’t mean they are necessarily better. They’re good at doing that kind of work but what you’ve got is really a fragmented market of all kinds of people doing different things.

‘It’s a chaos. There’s a real creative chaos to what’s going on.’

Deciding to make cameras

Meanwhile, the industry was switching from film to digital cameras. Cinematographers did not want to turn into television people, with all the limitations of video-derived gear. Instead, they were demanding cameras which had all the beauty of film, which had evolved technically over a century and combined exquisite chemistry, rock steady mechanisms and wonderful lenses.

The Arri D20 came out at the end of 2005, and the Red One started to ship in 2007, and the industry began the twisty technical journey to marry the older aesthetic with the new opportunities.

Blackmagic had a different viewpoint on the production landscape. Away from the high budgets of feature production, the vast majority of recording was done on a myriad video and then digital cameras designed for television, news and corporates. They were often called prosumer lines.

‘But the problem is the cameras people were using were video cameras and everything, you know, which might have nice pictures but they are nice pictures you can’t calibrate.’ Petty said. Filmmakers were able to take very limited advantage of digital technology.

‘You need more black range, you need more resolution, of course but what you are really after is dynamic range. You need to capture more of the scene so you can actually manipulate it. And we just didn’t have anything coming into DaVinci so we were frustrated by the lack of creativity – you still had to go out and hire a $50,000 camera with an $80,000 lens to get that quality of material coming in so you can really take advantage of what DaVinci could do.

‘So I thought that what we needed to do is create a low cost digital film camera, and that was what drove that. We joked that it was really a DaVinci peripheral.’ The company now has an evolving range of cameras for staggeringly low prices, which accept 35mm still lenses, run the smaller 4/3 chips, and maximise the post-production possibilities in a very full marketplace.

Read more here: Cameras: is that new camera in the window oh so last week already? in which cinematographer Erika Addis explores the benefits of the Petty philosophy in designing the cameras.

Revolutionary fervour

Grant Petty claims that the Blackmagic brand is misunderstood.

‘I never do market research, you can’t research what doesn’t exist. And so people don’t understand really who we are. There’s an underlying kind of revolutionary fervor that runs underneath the foundation of this company.

‘What focuses us is making the top quality stuff for high end work. But at the same time, I’m going to get my operations and everything right so I can actually make that affordable so anyone else can buy that.

‘Why shouldn’t a seven year old be able to get the same quality as in Hollywood? It’s elitist and bizarre and flawed to think that they can’t. Just because no one else ever did it before doesn’t mean it’s not possible. You just have to work that problem through, you know.’

In Melbourne Blackmagic employs around a quarter of its total staff on engineering, marketing and a small amount of manufacture. Petty is substantially hampered by a lack of trained staff as he watches good graduates go home to their own cultures overseas. In a sense the company has learnt to follow them to their nests, as it built seven manufacturing and sales bases around the world.

Petty has been systematically deconstructing the technical elements of screen production with a keen eye for fiefdoms and underlying cultures. He is no fan of traditional seniority.

‘How many industries do you know where the best creativity comes from the 50 year old guy who’s been doing the same system for the last 20 years? You don’t say that ever in human history. The creativity comes from new challenges, and new ways of doing things and hungry people with ambition who want to prove themselves stylistically.

‘If you don’t educate young people to be smarter than we are then ultimately we won’t get a better future because the only way we can get to a better future is younger people need to be smarter than us.’

‘The stage people dance on’

That cynical culture he encountered in business in the 1990’s has been growing worse.

‘Business is a way of organising people to do something but it seems to be the thing that doesn’t trust people. It’s a bizarre model. Everything seems to be an asset to be traded. Essentially we just hid from the world – we just developed our culture and a method for being creative and letting people be dignified in the way they could do engineering and doing things. People don’t have to do progress reports and prove profitability here before they make it, if its a good idea we just make it. If it solves the problem let’s make it. It’s a very fundamentally different thing.

‘People are smart, you know. The guy at the coal face should be making the decisions. Give him all the support he needs. The only person that should understand the coal face is the guy at the coal face. But he make the decision. And then my job is to support him.

‘This is like an upside down pyramid, right? I’m at the bottom supporting everyone trying to get everything they need to do, the wonderful things they do and you’ve got to trust people, you’ve got to believe in people. But I don’t think this is a culture that believes in people – its something to be controlled and managed, it’s a hierarchy of power. Business isn’t a hierarchy of power – it’s a way of bringing people together to do extraordinary things, and the creativity is where the growth and wealth comes from.

‘But I think that people are amazing. People are at their best when they are doing lots of interesting things all independently of each other and we just have to be a foundation for that. We have to be the stage people dance on. And that’s all we are – we are just the stage people dance on.

‘The equipment doesn’t matter. What matters is the people. I’m just pumped by what people do.’

——-

The various cameras in the range are designed to deliver the best possible signal for processing, without prior compression. The functions, connectors and ergonomics vary widely. Here’s a review for an earlier 2013 model of the Black Magic Cinema Camera. The Ursa Mini, evolved from the fully high end Ursa, was reviewed at the beginning of 2017. And Australian hire and sales company Lemac pitches the new Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 4k body.

——-

Here is the whole Hyperlight film, made with Blackmagic as a partner in Montreal by Second Tomorrow Studios.

And here is Grant Petty in conversation late in 2017.

.