There are some moments of serendipity which are just delicious. This is one of them.

Bettina Dalton is a wildlife filmmaker and archive experts who gathered an extensive film library through Absolutely Wild Visuals and Content Mint before forming Wildbear Entertainment with Michael Tear, Veronica Fury, and Serge Ou.

Her latest production is Playing With Sharks: The Valerie Taylor Story which will have a cinema release in Australia through Madman and has been sold to National Geographic, which is now part of Disney and can give the big streamers a run for their money. This is a prime, prime deal.

Beauty

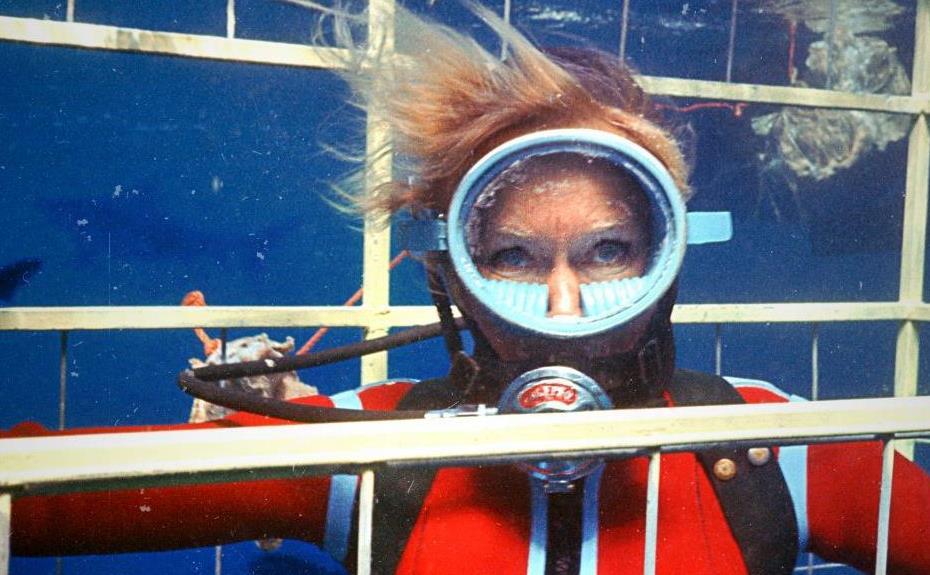

When Bettina Dalton was a child, she saw a picture of an extraordinarily glamorous woman with a wetsuit and blonde hair in a halo beyond her mask, one filnned leg delicately vertical like a dancer on the front cover of a 1973 National Geographic. ‘That made me learn to scuba dive,’ Dalton told me in an interview. ‘The moment I could legally do it. That led me to become a natural history filmmaker.’

Dalton’s first film was about black rhinos in Africa, while the woman who inspired her was Australian conservationist, filmmaker and diver, Valerie Taylor.

Now, Dalton has closed the circle by producing Playing With Sharks: The Valerie Taylor Story, directed by Sally Aitken. At the age of 83, Valerie Taylor is full of life, wisdom, stories and humour, eight years after her partner Ron Taylor died.

The pair started diving together in 1963, hunting fish for food and sport. For the income, they took to shooting underwater films, with names like The Underwater World of Ron Taylor, featuring his narration. Valerie was a fabulous sidekick, but of course she was a full partner in the enterprise, even though she slid slowly from image to oblivion as the sector moved on and the pair aged.

The 1973 series Inner Space did well for them.

Eventually Valerie Taylor was a side note, even on Google. In fact, the two were on an ethical lifetime journey which took them from killing fish to championing sharks with all their considerable passion.

They were the first people to film sharks from outside a cage, and they famously worked on the underwater scenes in Jaws with Stephen Spielberg. Over their working lives, they saw the total number of sharks in the world decline by 70%. They shot the Great Barrier Reef and gradually realised it was dying by inches.

All that time they filmed and filmed and filmed. They have probably captured one of the great atrocities committed by our species. As Dalton said, ‘You know, she spent years and years, decades under the sea, as a firsthand witness.’

Among a huge amount of other footage, Bettina Dalton acquired the rights to onsell the Taylor footage, which was transferred to video. Dalton made a three part series on the Taylors for National Geographic 20 years ago. Then she saw Jane, the feature length documentary about Jane Goodall, in 2017.

‘The Jane Goodall story. I just thought, hang on, archive… incredible woman.. in the wild? We have our own Jane, right in front of us. How come I didn’t see it before?’

In 2018, Dalton took the first outline of a film about Valerie herself to the Australian International Documentary Conference, had strong interest and went to Sundance in January 2019. The time was right for the film – the story of ocean decline, the rise of the feature documentary, the spreading truth about the role of women, even the funky story of Jaws, were all compelling. By focusing on Valerie Taylor, they had a fresh take, with different feelings and wisdom.

At Sundance the Dalton team joined forces with Dogwoof, the UK international documentary sales company which had supported films like Blackfish, and understood the power of this film perfectly. They provided a solid distribution guarantee which helped to finance the project.

Archives

Dalton and Aitken went back to that archival footage, got rid of the daggy transfers and started again with the raw, pure film footage. It is a treasure. The Taylors really knew how to make an underwater film, all the way from taking a deep breath and diving after fish, to exquisite 35mm.

As Dalton explained, she often deals with a huge amount of footage which is degraded and unlabelled, turning up as a heap of cans with a nasty vinegar smell. The Taylor footage was in pristine condition, with just two rolls over a lifetime that had deteriorated.

Ron Taylor meticulously recorded each species in notebooks, and logged each shot. Much of it was raw rushes rather than a version derived from cut film. That is a huge advantage, because they are camera originals.

When the Taylors started, said Dalton, ‘They had no money. They were living hand to mouth and every roll of film would cost them a fortune. They had to go and sell some fish to buy another roll, so Ron would button off the moment he had the shot. We basically went through hundreds and hundreds of cans, admiring his skill all the time.

‘And we scanned it all, because it made sense for Valerie to have a record on hard drive that is easily accessible. It took us about eight months to go through that film.

‘We had to hand-clean the film and scan it on a Blackmagic Cintel scanner. We were able to use 4k on the 35mm, but some rolls just didn’t hold up so they are on 2k. We had some young people working here, who had never seen the way films used to be made. And that was an education in itself, showing them how to chequerboard between two rolls with black in between.’

As Dalton teaches these skills, she keeps saying to them, ‘You’re one of the few people who is not retired, who knows to do what to do what you’re doing. You have to make sure you tell other people, just to keep the skillset alive and understand the heritage of filmmaking as well.’

A life redeemed

Even after a lifetime with archival work, Dalton is awed by the result. Meticulously cut by Adrian Rostirolla, supplemented by modern footage in Fiji, completed with simple, honest interviews with Valerie Taylor and featuring a score by Caitlin Yeo, the film is carried by sheer cinematic beauty and a story of redemption and disaster.

There is a clip on Vimeo, guarded by privacy settings but still accessible.

The film ran online for Sundance 2021. Bettina Dalton is a pragmatic, modest person who is cautious about the response. ‘It is really hard, to be honest, to feel what was going on in Park City but we certainly felt a lot of love from the audience. There was certainly a buzz in the press the next day and we had a brilliant publicist in New York, RJ Millard. That was certainly money well spent. The trade press is pretty happy, admiring the skill and beauty, getting the interior journey, hooking into Valerie Taylor’s spirit. She is still diving today in her pink wetsuit. There’s a couple of dissonant voices, but not much.’

Besides the record of a remarkable life lived with joy and growing self awareness, there is a lot of fun in the film about our changing culture.

‘Even kids who don’t know Valerie’, Dalton said, ‘when they see her, there’s something captivating, like a Bond girl in those retro outfits where they just can’t stop looking. She’s an action figure, and yet she’s also the woman who we knew from the Women’s Weekly.

And the person who described her very first encounter with a great white shark as being ‘like a freight train coming out of the mist.’

[This article was originally published 12 Feburary 2021]