I first met Madeline Miller about ten years ago at a boring luncheon full of lawyers and film industry execs. Laughing and lively she was a burst of sunshine at the table, but not a lightweight. We talked about her time in Cambodia as a lawyer assisting in the United Nations’ prosecution of members of the Khmer Rouge; and later, as legal council at Screen Australia, drafting distribution and financing contracts, dealing with IP, copyright and tax, and all those other bits of scary paperwork that make the world go round. But it was clear her passion was for people and ideas, and she loved the movies.

So it came as no surprise afterwards she moved to the United States to further her career as an entertainment lawyer in a much bigger screen industry. Nor was it surprising that she continued to do pro bono work for the Human Rights Arts and Film Festival back home.

Then we heard her latest job was as production attorney for the 21st James Bond film, No Time to Die, due out through Universal in 2021.

Now known as a ‘business affairs and global brand partnerships specialist’, she worked on the product partnerships of one of the world’s largest film franchises. We wondered what that was like. How does that part of the business operate? And what does it feel like to be an Australian entertainment lawyer progressing fast in the boardrooms of Hollywood?

Answering these questions by email, Madeline told us about her unique pathway, about the importance of empathy and communication in getting deals done, and why she doesn’t think it’s necessarily selling your soul to the devil to align stories with brands. She also has some hair-raising observations about sexism women encounter once they hit a certain level of success.

Screenhub: Can you talk briefly about how and why you chose to enter Law as a young person, and then later to follow the path into the film and entertainment industry? What attracted you to the field?

Madeline Miller: Like a lot of mid twenty-somethings, I was torn about where I was going in my life. I had an Arts degree and Honours year from a prestigious university, but also a yearning to do something creative. There was fear and probably some insecurity about how to best achieve that. I was so young, but felt too old to be ‘starting from scratch’ again. I also had a burning sense of social justice and was strong in advocacy and had always drawn comfort from the structure of academic life, so a law degree seemed like the right solution to bide some time, looking like I had direction and like it could possibly open doors for me in certain industries and areas I knew nothing about. I think there was a overwhelming sense of having to prove myself, whilst also never feeling like I fitted the conventional mould of a lawyer. For whatever reason, I felt like a Law degree was going to get me closer to working in the film industry and doing meaningful human rights work, which had both always been my passions. So I enrolled and hoped for the best!

How long have you been living and working in the US, and what led you to make that move?

After I finally broke my way into the Australian film industry as a Screen Australia lawyer I felt like there was a small pool of work and a small pool of experienced people already doing it. I didn’t know how to break into commercial television and also, wanted to experience being a Masters student in the U.S. and try my hand at getting work over there. So in 2014 I applied for a bunch of universities and eventually settled on UCLA as it was the school that had both a good reputation academically and was known for its entertainment law program. It also has a prestigious film school that I could study producing in as a side subject.

Read: What is the future of Australian screen exhibition?

Has it been hard to break in to the industry there, and are you part of an expat community?

It is hard and although I don’t feel like I belong to any expat community, upon reflection my first real job was being hired by an Aussie and referred to by an Aussie. There are a limited number of Australian lawyers/business affairs executives working in the industry here but the ones that are, are pretty impressive and hold senior roles. I think like a lot of close knit industries, it is hard to get that step on the first rung of the ladder, but once you do, if you do a good job, you keep progressing from there.

What was the particular training that you did at UCLA to help you with this specialised field, and are there many lawyers in this area?

There is definitely an established and large ecosystem of entertainment lawyers, production attorneys, and in house legal and business affairs executives in Los Angeles and New York.

The distinction between legal and business affairs is something that you get at the larger studios or production companies and doesn’t really exist in Australia. Basically, where there is a split, business affairs will do the negotiation of the deal points and legal will then draft and negotiate the remaining ‘legal’ points. I think I had the legal training before I came to UCLA but I was given the opportunity to do internships whilst studying and that helped me become familiar with the language of the deals and the forms that are used for talent and other rights agreements.

UCLA also gave me the opportunity to study subjects dedicated to film financing, film distribution and the Hollywood guilds, which you would never get in Australia at a law school (and would get at few law schools in the US) so this was a really incredible opportunity to learn more about the Hollywood industry and become acquainted with its customs and norms. Of course, nothing really turns you into a good legal/BA executive like hands-on experience, and it wasn’t until I got my first real job and the stakes suddenly became quite high that I really stepped up to the plate.

What has surprised you most about living and working in LA? Did you have preconceptions that were proved wrong or right?

I don’t really think I had any idea what I was getting into. I have seen some of the craziest behaviour whilst not even working at some of the craziest companies. I think I have also been struck by how much deal-making in this industry relies upon customs and norms that are sort of reproduced over and over again to become industry practices, but to an outside ear or eye, a lot of the language wouldn’t even make sense, there is so much jargon.

‘Los Angeles is a place where people come to broaden their horizons, to escape, to dream big and sometimes all three…’

There is also a lot of ego and posturing and faking it. But I think, somewhat in opposition to the previous opinion, I have found living in LA to be a lot more real and down to earth that I imagined. Juxtaposed with all egos and posturing are a whole lot of good, socially progressive, educated people who might love the industry, but are also grounded and ambitious without fitting the mould of ‘Hollywood’ that you see on TV. Los Angeles is a place where people come to broaden their horizons, to escape, to dream big and sometimes all three, and I think because of that I have met some of the most interesting, talented and exciting people from all over the world, not just in the film industry. [I’ve found many people] with whom I have a shared sensibility, despite having come from a completely different place.

What have been the most useful personal or professional qualities that you brought from your Australian experience to your LA career?

In my opinion, the best Australian qualities are that we are direct, hard-working and conscientious without being obsessive and overly anxious. Obviously, that is a massive generalisation and I have been the opposite of all of those things upon occasions. But generally, I think people like Australians, and we carry with us an intelligence and affability without an enormous heaviness as we’re such a lucky (and yes, often therefore politically apathetic) country. I have learned in the US to be more assertive, less apologetic and probably less direct. Americans are the masters of genial small talk and enthusiasm, but deals can evaporate behind closed doors. I’ve learnt to play more of that game, without losing my full Australian ability for directness and truthfulness, and I think that it is appreciated. I’ve had to tone down sarcasm though as it is not well received or understood in the workplace unless you are on good terms with the other party.

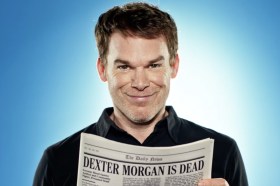

Your latest role has been as production attorney on the new James Bond film No Time to Die. Who are the main people and roles that you liaise with, and what is the most exciting part of this job? And the most onerous?

I hadn’t been a production attorney before No Time To Die so I was surprised at how varied the role was. There was less of the talent negotiations that I had been used to as this was managed by specialist talent law firms and there was a lot more work to do with the nuts and bolts of production, such as reviewing terms and conditions for equipment hire, charter flights and purchase agreements etc. I also was more involved in clearances than I had previously been, and drafted a number of production services agreements for our relationships with local production companies in each of the jurisdictions we were filming in and seeking a tax credit.

I reviewed and often negotiated a lot of location agreements and got heavily involved in the promotional partnerships and product placement deals for the film. It was a lot more practical and applied than a lot of the rights, talent and financing work I had done prior and it actually relied more heavily on my general commercial and contract legal experience and knowledge a lot of the time rather than straight up ‘entertainment’ law. I was based in Pinewood Studios for a lot of the work I did and saw some of the amazing sets being constructed. I did end up travelling to France to negotiate a large location and promotions agreement for a location in Jamaica and then travelling to Jamaica whilst this location was being used. Most of the production team went to Italy for the final part of filming but I had returned to LA by then and was working from my home office!

Madeline Miller on location in Jamaica for No Time to Die.

The Bond Franchise is one of the oldest and most prestigious luxury film franchises – and as you said in the Screen Australia podcast, one of the rare franchises for older viewers rather than younger ones. What are the main brand partnerships involved here, and are there some particularly distinctive new ones to appeal to a younger audience?

There are a few longstanding relationships with brands such as Omega and Bollinger and Aston Martin, to name a just a few, and then for each film certain new partners are brought in. For example, for No Time To Die there is a new partnership with Nokia and Smirnoff vodka. The franchise itself has a longstanding licensing division which is expanding and there were a lot of new licensees brought in to release Bond-themed products to align or coincide with the next film’s release, but which continue on outside of the film’s promotional period. A lot of these licensees are in sectors that appeal to a younger more diverse audience such as streetwear apparel and footwear. Similarly, a lot of the partners and licensees are activating marketing campaigns in less traditional forms of media such as print and television and doing more online and digital, using ambassadors and influencers and more social media based campaigns with experiential components such as gaming and interactive elements. These kind of campaign elements are a definite move towards engaging with younger Gen Z audiences. It is all about brand alignment and getting the new generation of viewers and franchise devotees.

Does it ever strike you as cynical, the combination of brand partnerships and storytelling? What are the ways this can be done well?

I’m actually really positive about brand partnerships and storytelling. I’m not suggesting that it works for every film, but commercial filmmaking is a business and anything backed by a studio has got a whole marketing and publicity department working behind the scenes to get the most amount of coverage and press for a release at the right time to maximise its profit. This is what Hollywood studio film making is. I therefore think that the right partnership can be a really fun and exciting way to generate publicity but also lead to some really creative and fun ideas.

Entertainment and brands/advertising are becoming increasingly entwined, but their relationship is not new. The Super Bowl commercials are an excellent example of how the combination of the two can create an institution in and of itself. People tune in to the Super Bowl just to see these commercials now for their cinematographic quality, their humour and often their tongue-in-cheek absurdity. Brand partnerships with significant film IP is no different. The people who work on partnerships and licensing for Bond are amazing and have all been doing it for a really long time. People look forward to the Heineken ad with Daniel Craig each time a new Bond film comes out, and people love seeing the new Aston Martin or Jaguar Land Rover launch. I think it obviously works better with big budget genre films but Bond is a great example of how the partnerships can become an extension of the storytelling and build more anticipation for the film.

What advice would you give to Australian film or TV producers wanting to think about brand alignment? Are there any transferable principles?

I would say that there is a difficulty in comparing local Australian films to international Hollywood films, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t lots of opportunities for entertainment partnerships with local content. Entertainment brand partnerships tend to work best with action, animation or kids films, but this is not a fixed rule. I think these days a lot of brands are looking to tell stories that resonate with younger audiences, such as Gen Z which is the next generation of consumers. So if your film or series includes or centres around issues that Gen Z are particularly concerned about, such as climate change, diversity (gender, sexual identification, race), sustainability and political representation then there are ways to partner with brands. This could be via talent, crossover collaborations or traditional advertisements that are more organic and creative than a simple product placement. In this way, brands can share in the storytelling, while aligning themselves with the audience’s interests. I am less cynical about this than earlier decades of advertising as I think audiences are now pushing brands to be more accountable, rather than brands having so much power in shaping cultural discourse.

‘Entertainment brand partnerships tend to work best with action, animation or kids films, but this is not a fixed rule. I think these days a lot of brands are looking to tell stories that resonate with younger audiences, such as Gen Z which is the next generation of consumers.’

In what ways do you see your job as creative? How do the ideas of creativity and art play out in your own life?

I am constantly having to come up with creative ways to address and solve problems. I think I see myself more as a communicator than as a lawyer, and whilst I obviously have to understand legal principles a lot of what I do is crafting language to reflect what people want (or what I want people to want!). Or, it is managing people’s expectations and communicating needs and expectations between multiple parties.

I think to be a good business affairs executive you need to be a good strategist, have good business instincts and also be a bit of an empath. You need to be able to understand both sides of a problem but rally to have your side’s position understood. A lot of the negotiation in Hollywood is smoke and mirrors and there are techniques and strategies that you have to deploy to go through the process to get to the end goal. This has been an evolution and learning process for me, because I tend to rush to the conclusion which is clear to me and try and have everyone catch up. But I’ve realised how important the relationship building and the communication is, and how much flexibility you need in order to manage a whole range of issues, egos and personalities across legal, finance, marketing and talent.

Read: Glendyn Ivin’s hotel quarantine: a strange sense of freedom

Are there any mentors who’ve been instrumental in helping you progress?

I have had a couple of people along the way that have really taken me to the next level in my work. Some of them have come from unusual places, like in house government lawyers. Most recently the managing director at Eon, David Pope, who is also a lawyer and co-producer for the franchise has been a really good sounding board as I can sense check things with him that I am uncertain about as we usually think the same way, which is a little bit more pragmatic than strictly legal. He usually elevates what I am thinking given his vast experience but also makes me trust my instincts as we are usually in sync. I think the fact that he is a Kiwi helps as we have a similar antipodean sensibility!

As a woman in your field, is sexism a concern for you?

Yes. I mean you can’t avoid it. I found that a couple of years ago as I started to get more senior, more knowledgeable and more assertive I started feeling the glass ceiling really push down. I think there is a professional period for a lot of women where (some) men applaud and elevate you, which you need because sadly they are still in the majority of decision making positions, but then you reach a point where they decide that is enough and you pose too much of a threat and they don’t feel you are malleable anymore. For me that is when it got really lonely and hard. Also, I have sat in numerous meetings where I am the only woman who is not an assistant, and the locker room talk that goes on is gross. I have been told to ‘put my Big Boy voice on’ and that I am ‘having a blonde moment’ by men who are younger than me but in more senior positions.

Can you finish this sentence: If there was one thing I wish people understood about my job it’s….

…that it’s nothing like they teach you in law school!