Japanese film director Kō Nakahira (1926-1978) was a projectionist who opened fire on a nation’s hardline stance on sexual expression. Over a decade in which Japan saw socioeconomic disparity between the younger generation and the old, Nakahira’s filmic persona presented a unified and twisting description of psychosexual taboos in Japanese New Wave cinema.

Suna No Ue No Shokubutsu-gun, Flora on the Sand (1964)

Cosmetic salesman Ichiro Igi is a martyr to his own desires. Consumed by thoughts of his father’s alleged lovemaking with his own childhood sweetheart, he divests all of his attention to the profane. His sexual exploits continue to jag downwards. After soliciting a young girl in uniform, he promises to aid her in sexually humiliating her older sister after making her his mistress.

One scene presents a woman who strips elaborately to a traditional dance in a private show – a nod to the Japanese origins of jōruri and nagauta in kabuki theatre. She prostrates herself on the floor, and the stymied motion of her arms uncovering her body implies nudity though it is never shown. The camera cuts to a shot of three men behind a panel in pitch darkness, except for their eyes that emerge from a solitary slant of light as glowing embers. The woman’s vague, writhing form is slowly reflected in their pupils.

Perversion here becomes a thing of mythology; the men talk about groping over tea, and during a haircut Ichiro is told about a married brother and sister who ran a small eel business from their house. They kept all doors locked, except for a delivery window where they exchanged contra for their suppliers. They never parted with the eel livers. This, suspects the barber, was because the two kept those sacred parts to eat for themselves. The conversation and lore presents as a kind of sensationalised proxy that can be read as a cultural attitude towards the despondent and depraved.

Read: Film review: Little Blue, Taiwan Film Festival in Australia

In the sexual climax of the film, as Ichiro wrestles with his disjointed needs, the sisters coalesce into one another – the elder sister, who is openly sadomasochistic and shares an affinity for rope play, and the younger, who is a vengeful schoolgirl. Ichiro makes the firstborn wipe off her lipstick and the latter smear some on with force. The sisters’ faces merge in-frame, panning back and forth between the two to form an indiscernible blob, now both have culminated in the nebulousness of Ichiro’s own frustrated desire for union. With whom? It doesn’t really matter. For all his mania, the women are little more than props.

The beauty of the female form and the depiction of sexual advances are both confined to delicately gratuitous visuals – lace-crimped undergarments dropping onto a tatami mat, a crimson blob bleeding its way atop of a tricoloured mural, the motion of a woman’s back retreating into darkness as a man follows in pursuit. With a film that is heralded as a trailblazer of the Pinku Ero-production of Japan, Nakahira is evocatively succinct without being ribald.

A bridled descent into madness, Flora on the Sand typifies the indecipherable – what a man wants to take and cannot have is paralleled in grand scale with his nation’s own margins of restraint.

Flora on the Sand was screened at the Chauvel Cinema, Sydney on 24 October as part of the Japanese Film Festival.

Kurutta Kajitsu, Juvenile Jungle (1956)

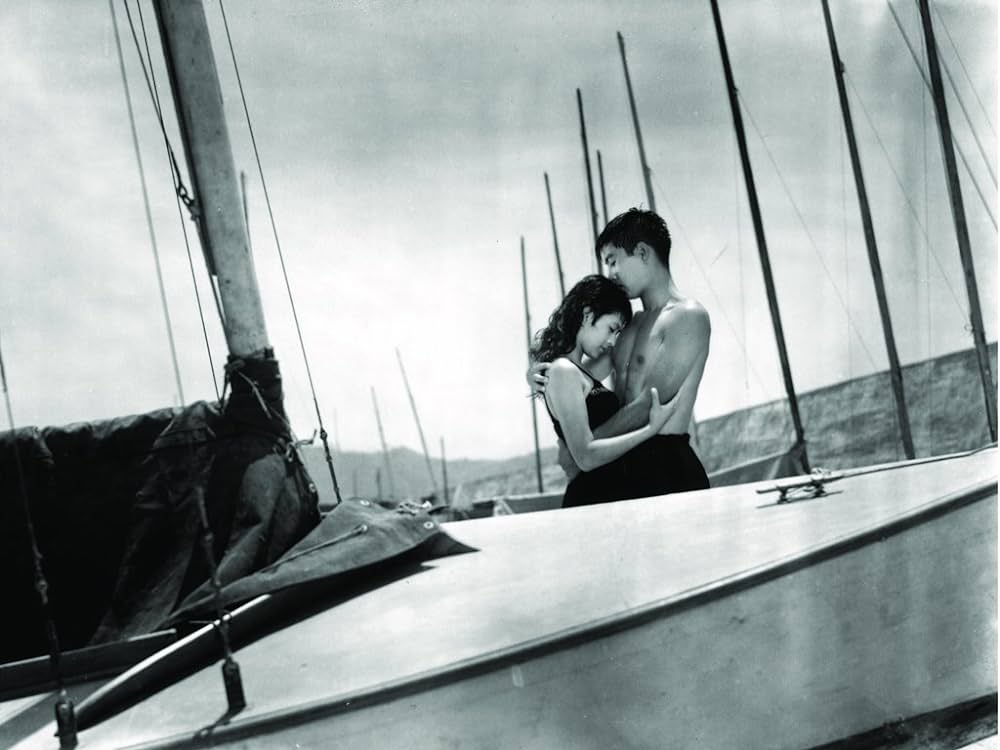

A fanciful take on the youth-engineered “Taiyozoku” subgenre, Juvenile Jungle is a flighty epic of lust and betrayal, based on Shintarô Ishihara’s novel Crazed Fruit. From the perspective of Japan’s postwar disillusioned youth, Nakahira spins a tale of conflict between two brothers over Eri, a woman not yet 20 years old, who is intent on revealing very little about herself. The film is set in coastal Japan, fringed by sun, sea and a considerable smattering of Americans. Adults are notably absent – perhaps the only recall to the fact that a war has just occurred.

The connective tissue of the plot is perhaps the least compelling element of the film. What is left, however, shimmers to life in dialogue and idyllic presentation. The filmic architecture of Juvenile Jungle is uncompromisingly breathtaking; the shots of the young and beautiful playing near water present landscapes in the lush summer – the heat and brightness poking through the black and white film in equal measure. Oblique references to the classic New Wave of French cinema of François Truffaut can be traced to the restlessness of the youth, who spend their days boating and lounging around, often consorting with other young women.

Western influence is exerted in spades, down to the drinks ordered (whiskey, neat), the attire worn by the female cast (full-netted dresses with billowing skirts, capris paired with headscarves), and the occasional snippet of English – employed here to situate the forceful presence of the American other, and the societal need to defer to it.

One scene features Frank as the only one out of the troupe of disillusioned boys who orders shōchū (a Japanese distilled beverage) at a nightclub. The waiter, recognising that he’s half-white, switches to English, which is rebuffed coolly by Frank’s native command of Japanese.

These ideas are recouped and reworked as vain, flighty arias of the youth, untethered to the Japanese pre- and postwar narrative of restoration and superciliousness, tepidly warming to the Western projections that hold the entire nation hostage, while self-conscious of their position as inferior to its givings.

Even the brothers, driven to madness over the same woman, must concede to her status as the wife of a white diplomat. They wrestle with one another, convinced of their indomitable right to take, to claim Eri’s affections – sexual and emotional – in a warring domain that never interferes with her marriage. At heart, the boys want love and power, but have no inherent understanding of how that can take shape without seizing what they feel to be theirs.

The ending, for all its lurid violence, finds its identity among the disorder. Destruction is the birthright of these cusp-adults, and there is no destruction more looming than the crazed fruit of adolescent desire.

Nakahira is an évocateur who kept pace with the rapid transformation of Japan’s rebirth. Through widespread themes of sexuality and desire, Nakahira’s filmography arcs through repression and taboo with explosive grace.

Juvenile Jungle was screened at Chauvel Cinema, Sydney on 25 October as part of Japanese Film Festival.

This review is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: