‘In this day and age there’s a lot of despondency about politics,’ says Lou-anne Barker towards the end of Women of Steel, ‘and people have lost the understanding that if people get together we can be strong! We can achieve a lot.’

This 56-minute documentary feature follows a group of Wollongong women over their 14-year fight for steelworks jobs with Australian Iron and Steel (AIS), a division of industrial titan BHP. The film’s director, Robynne Murphy, was herself a steelworker and a member of the collective that took BHP all the way to the High Court.

She was also a promising filmmaker who’d been selected in AFTRS’s very first intake, and whose first documentary, Bellbird, played the Sydney Film Festival in 1974. ‘So I just picked up my little home movie camera and started visiting all the women in the campaign,’ she recounts onscreen in Women of Steel.

The archival footage of Wollongong in 1980 reminded me of kitchen-sink social realist cinema. Stoic women trudge along shabby, sunbleached streets as seagulls wheel overhead, while in the background rust-red mill towers belch steam and fire. A grim place.

Slobodanka Joncevska remembers her first impressions of a city that ‘was looking more poor than my poor country, Macedonia,’ she recalls. ‘Wooden house, fibro house. No modern life for the young generation.’

At the time, Illawarra industry actively recruited migrant workers – but almost two-thirds of the city’s unemployed people were female. In 1977, NSW state legislation had officially ended gender-based workplace discrimination; but women still butted against a steel ceiling. Many of the Illawarra’s migrant women had worked in heavy industry in their home countries, but here they were forced into insecure, unregulated garment-industry labour as AIS relegated women to ‘feminised’ domains such as the cafeteria. Female jobseekers languished on waiting lists of 2000 names for up to seven years, watching men get hired after just weeks.

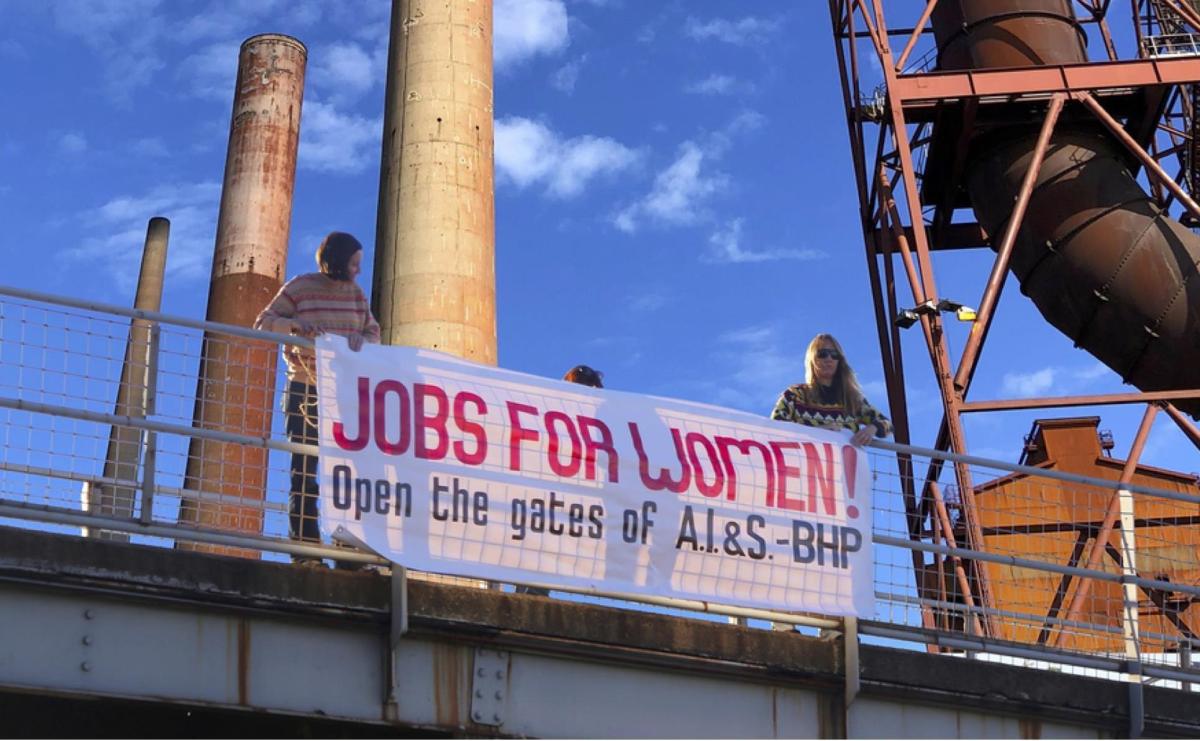

Murphy was one of four young socialist women who arrived in Wollongong determined to make a difference. Along with Barker, Diana Covell and Louise Casson, she co-founded the ‘Jobs for Women Committee’. Emboldened by the tactics of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, the activists set up camp outside the factory gate, handing out multilingual leaflets that male workers in turn passed on to their female relatives.

What’s heartening about this campaign is that Wollongong was a multicultural, left-wing town, and the local union movement took up the women’s cause because it insisted all members deserved the same protections.

In honouring women’s political agitation in Australia this film overlaps thematically with Brazen Hussies; but while that documentary is energised by the scope of the activism it depicts, Women of Steel is about the payoff – and payout! – that comes from dogged perseverance. The film doesn’t shy from depicting the women’s drawn-out struggle, stymied at every turn by BHP’s exclusionary tactics.

What’s heartening about this campaign is that Wollongong was a multicultural, left-wing town, and the local union movement took up the women’s cause because it insisted all members deserved the same protections. Or as Monica Chalmers, from feminist union lobby group the Working Women’s Charter, puts it impishly: ‘The best man for the job might be a woman.’ It says something about how solidarity worked here that the mining union provided their comrades with coal to make campfires in the freezing Illawarra winter.

Women of Steel certainly feels made by a worker rather than an artist. It’s pragmatic and unshowy, combining talking-head interviews and archival material (some obtained from WIN TV news coverage at the time) with dramatisations of some events. While some of these are obvious Media Watch-style voiceover performances, I – who was too young to remember this story as it happened – wondered if I’d missed other seams and had taken for archive material what was really a dramatisation.

In such a determinedly realist documentary, this unsettled me – but it also made me ponder how more formally ambitious filmmaking could have energised this staunch story. I glimpsed something more evocative, too, whenever Jan Preston’s soundtrack fades in what sounds like a Slavic women’s choir, or when the interviewees recall (but we never hear) a convivial ‘Guantanamera’ singalong with a group of visiting Cuban women. Even the closing credits sequence – a montage of powerful, capable women at work and play, over Mo’Ju’s anthemic ‘Don’t Stop Me Now’ – captured my emotions in a way the film itself did not.

Because of course, socialism and the union movement weren’t just about struggle. They could also be fun; and a few delightful moments here hint at the role of art in activism. For instance, there’s archival footage of a burlesque theatre performance dramatising the campaign’s central themes using ribald props, in a style I can only describe as ‘socialist pantomime’. An audience of assembled women guffaws as the rejected worker reveals her bra and underpants, while the hired worker reveals his manly jocks.

This important landmark in Australian industrial history needed to reveal more of the joy and play that surely motivated and bonded the women at its heart.

3 stars ★★★

WOMEN OF STEEL

Australia, 2020, 56 mins

Director/Producer: Robynne Murphy

Consulting Producer: Martha Ansara

Australian Distributor: FanForce

Release Date: Touring Australian cinemas now

Read: Film Review: Brazen Hussies celebrates the living history of Australian feminism

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: