Sydney Festival Director, and Noonuccal Nuugi man, Wesley Enoch believes we are facing a tipping point globally.

‘Most structures in North America, Europe and here in Australia, the centre is being vacated, and for those of us who have lived on the fringes for so long, we have the skills to now populate the centre.’

Enoch believes that as the new fringe swarms to the far left and the far right overtaking public debate with minority views, there is space for First Nations knowledge to move to the heart of conversations.

‘First Nations offer a logic in a way of bringing these conversations back to the centre. We have the skills to talk about a world that is inclusive and open … and we need to take our role very seriously. This is where leadership is for us,’ Enoch added.

So what should cultural leadership look like?

For Rhoda Roberts, a Bundjalung woman and Head of Indigenous Programming at the Sydney Opera House, is it about responsibility. She recalled a conversation with a colleague: ‘It’s about a difference in the way Western people see leadership to how we see leadership … leadership for our people is responsibility.’

It was a sentiment echoed by Aboriginal filmmaker Pauline Clague: ‘I don’t see myself as a leader; I see myself as a facilitator for other people to lead, and that is what a lot of our community does as Indigenous people.’

Being good leaders is valuing knowledge

Roberts prefers to use the word custodianship than leadership. ‘My challenge, working in a western system, is ensuring that our voice, at a community level, is given the ownership [on projects and policy], and that they feel included.’

She continued: ‘When I am doing budgets I always put a fee under “cultural custodians”, and people would say “a what?” We need to pay people for their knowledge – these people are our bush professors; they are our guides, and that is a level of leadership.’

Roberts also makes the point that we have been schooled to respect community and Country, but fail to recognise is it not only remote knowledge, but also valuing what is in front of us.

‘People say, “It was so good going to visit that community because I was on Country”; hang on, everywhere is on Country. Or, “I don’t want your voice; I want a community member”; just because I am successful doesn’t not make me less grassroots. We have to be very aware of terms we are using.

‘We are in a business – that is our profession; we have trained for it and we are good at it. We have to engage that cultural authority,’ Roberts concluded.

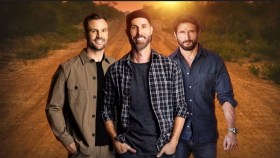

Wesley Enoch and Rhoda Roberts discussing First Nations leadership; photo Artshub

Enoch believes that leadership – any leadership – comes back to knowledge.

‘If we look at the major questions facing us as Australians, the environment is the number one issue, and it is all we are talking about because we feel that we need some leadership there.

‘For every question approached, First Nation Australians have an answer that comes from many generations, so why don’t we start with a First Nations approach?’ asked Enoch.

He pointed to the transference of knowledge offered in the celebrated recent publication of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu.

It’s not lost in translation; we’re just not listening

Clearly there are failings that remain deep-seated. ‘The Constitutional Recognition discussion cost millions of dollars and involved years of consultation that eventually came to the Uluru Statement – one of the most generous documents that was saying here is leadership, this is what we think we need – and within two days our central parliament had said no,’ reminded Enoch.

Artist and Artistic Director of 2020 Biennale of Sydney, Brook Andrew spoke further on that sense of embedded dismissal. He believes that leadership is so much more than an English word. ‘It is what we do together … the collective, and how people take ownership and lead by working with others – it is our creative story to tell and to lead others in its telling.’

Andrew makes that point that it is not a lacking of leadership qualities among First Nations, but that while our boardrooms are still dominated by white men making decisions there will remain paternalism and control.

‘What we need is the power of letting go; the power of allowing Aboriginal leaders to do that is mind blowing’ Brook Andrew

‘We don’t need autocrats; autocrats equal genocide. What we need is the power of letting go; the power of allowing Aboriginal leaders to do that is mind blowing … The peers we work with, who are non-Indigenous, they are the ones who have the power to say that we can work equally together.’

Roberts used the word trust as a key component of the leadership discussion.

‘We have to find people who trust our cultural knowledge. Leadership is engaging with our communities and showing them that having the faith to take on their cultural authority and place it on the main stage, because these stories have to be told from our lens.’

Senior Manager Aboriginal Strategy and Engagement, Create NSW, Peter White reminded: ‘Another form of leadership is to be able to listen. We all hear deep time, deep thinking, deep listening – that is First Nations leadership.’

Give us a level playing field, and we will lead

Only last month, one of the most prestigious international auction houses, Sotheby’s New York announced it would hold the first Aboriginal Art Auction in the United States, while across town at the mega gallery, Gagosian New York, presented two significant collections of Aboriginal art – actor Steve Martin’s collection and Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection – making the headlines of international art press.

It is only one example of how Aboriginal arts and culture demonstrate First Nations leadership globally. However, both Roberts and Andrew say there is a dire need for honest critique alongside representation, to truly value First Nations leadership.

‘When is it, that we can have an honest critique about the work without being turned into some disillusionment about racism; when is an Australian writer in this country brave enough to put our talent, our work, on the same level as any other theatre company without being paternalist – without giving an overview, rather than a review,’ said Roberts.

Leadership isn’t a conclusion; it’s hope

‘Most forms of [Western] leadership keep shifting so that Aboriginal leaders are in a responsive position, not strategic positions,’ said Enoch. ‘Every 15-years [for example], that’s played out from being referred to as Natives, to Aborigines, to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and now we are going into First Nations – each time we say okay we will use that, instead of saying, actually we are incredibly diverse.’

One of the inheritances of the 1967 Referendum is that we still have to pact together to negotiate at a policy level, added Enoch. Quoting contemporary demographics, he makes the point that around 50 per cent of our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island population is under 25 years of age.

‘We are about to hit a tipping point – we will see this generation that have had role models, and we will see a continuation of culture because of that, and not the kind of glass ceilings of ups and downs of the past.’

Clague added: ‘I don’t want to use the deficit any more. Give us the space to make the decisions and take the risks we need to take for our community … imagine if this next generation are allowed to be in a Ferrari in fast lane.’

But it was Roberts who had the last word: ‘If you have learnt to listen and read Country, you can cope with the mistakes, and that is great leadership – the power to lead is the confidence that you can.’

Top Jobs: Championing First Nations leadership roles was presented as part of the 2019 Vivid Ideas program.