Imagine you have just brought a baby into your family. Both of you are in a daze, astonished that you have created a small human between you. Within a day, the hospital staff tell you that your child is profoundly deaf. You are in turmoil. Why us? How could this happen? Can we live a normal life? You grieve for the silence inside your child’s head, and the isolation.

Over the months, you notice that your child gestures and smiles in certain situations, asking for food and cuddles. Her eyes follow you all the time, responding to how you move. You realise that your child is developing a sign language, and teaching it to you. Experts say that Deaf twins will create a vocabulary with its own grammar. Whole communities will evolve a common sign language even though it is suppressed at school.

Your doctors say that you must move fast, because a child’s brain needs to embark on the language journey before she is one year old. Cochlear implants are often fitted early, but even so, families often make the journey into Auslan. Your daughter becomes part of the Deaf community, and so do you, as a hearing and signing parent. To me, you have learnt something beautiful.

From my point of view

I am not a member of the Deaf community, though my hearing impairment started when I was seven years old and has grown slowly but steadily worse. Some 20 years ago, I was terrified of meetings because I could pitch but (secretly) not hear. Now I am kept on Planet Human with elaborate hearing aids which are improving year by year.

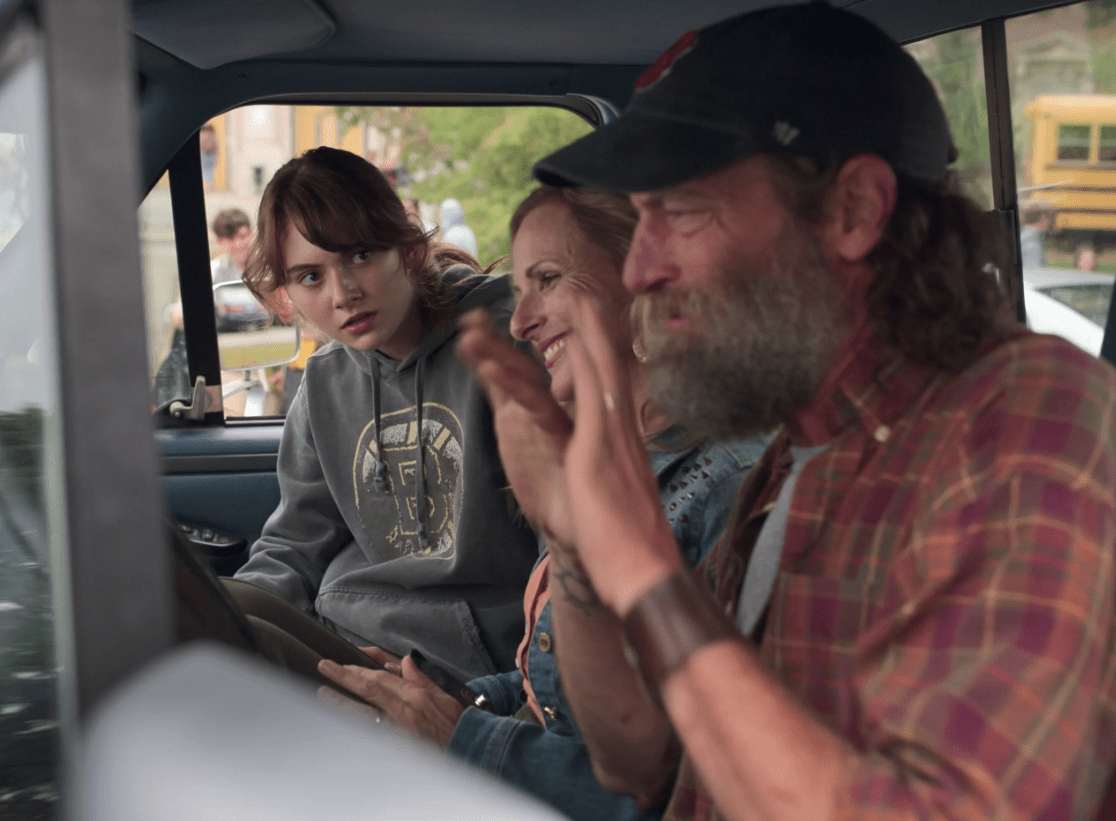

So you can see why I am fascinated by the two CODA films. After all, the US remake took Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor and Best Adapted Script at the 2022 Oscars, beating a magical list which included The Power of the Dog, Belfast, and Drive My Car.

The first version, La Famille Bélier, is about a Deaf French farming family dependent on their adolescent daughter who can hear – the Child of Deaf Adults of the term CODA. She can sing and is tempted to apply to a prestigious French music school, which will leave her family bereft. It is a comedy, the characters are very sweet, the hearing star Louane Emera is a hit and the picture did well critically and commercially.

I find the idea that music is a dreadful loss for Deaf people annoying because it provokes cheap pity, and ignores the fact that a visual language is itself a wonderful thing. But I liked the fact that signing actors had an important gig, and there are lots of details like the noisiness in the kitchen which are accurate.

Then I noticed there is not even a Deaf consultant mentioned in the credits. It turns out there is one informative Deaf actor but the major people signing don’t know the language and wave their arms around pretty badly. I was very pissed for the same reason as The Guardian:

Deaf people’s culture and experiences have long been appropriated for the fascination and entertainment of others, and in the process kneaded into a bastardisation bearing no resemblance to real-life experiences, because it is rare that deaf people are actually involved in the production process.

Rebecca Atkinson

When the American CODA was announced, my hackles went up. Producer Philippe Rousselet was still involved. The son of the businessman who set up Canal+, he is an experienced Warners executive who has run French-US production company Vendome since 2008. He inherited the original project in a takeover deal, but insisted in all the subsequent remake negotiations that he would produce.

Time for change

But times were changing, disability and authenticity were burning into the sector, and Rousselet and his partner Patrick Wachsberger needed to make the remake distinctively different. In 2016, they came across indy arthouse director Siân Heder around Sundance as she attracted attention with her first feature, Tallulah. She came from a family of artists, trained as an actor, makes intimate family stories and is politically aware. She has vision and determination and calmly offered a wild ride.

She pitched the idea that the story should move from a dairy to a fishing village – specifically Gloucester Massachusetts, where she had spent a lot of time. The town was declining, and grimly holding to the sea and small, battered trawlers. What is more, she wanted Deaf actors who could genuinely sign.

The keyest key actor is Marlee Matlin, who won the 1986 Best Actress Oscar for Children of a Lesser God, who is joined by veteran actor and director Troy Kotsur, and Daniel Durant, who is also active in television. They all learnt American Sign Language from an early age, are graduates of Deaf education, and thrive in Deaf theatre.

Into the language

Siân Heder began to learn ASL immediately. The script was written in English and translated into ASL, using a written notation system and the memories of the two ASL Masters who were the custodians of the Deaf world view on set.

Looking for a teenage girl who could sing, fitted the performance style, shone as a person and felt totally authentic, they ended up with Emilia Jones, who is English, started acting at the age of ten, and has been in Dr Who. Over nine months she too learnt ASL, and the particular accent of small town fishing people in Massachusetts. She also took singing lessons.

The translation process was epic – there are no less than seven translators in the credits. They had to be everywhere all the time, working with actors, carrying instructions, mediating closely between crew and performers. The crew learnt as much ASL as they could.

The hearing people had a full on collision with the world of Deaf. As I know well, any hearing impairment structures your social behaviour. Is the light right to lip read? How do you attract attention? Can you speak from behind? (No). Can you startle people? (Yes). Do we spread out the same way through a room? (No.) How do we wake up? (Reluctantly) … and so on.

To make matters even more complicated, the cast often improvised, while the comedy was startling and spontaneous. Every element of the production was affected. The sizes of shots, the lighting, the blocking, the rhythm, the way attention and point of view moves in the edit. This is a mini-world with a different kind of language, obviously visual but also more cinematic in subtle ways.

As Siân Heder wrote in the LA Times:

When I started studying ASL, it struck me how different it is from spoken English. It wasn’t just the grammar and syntax, but also that the methods used in ASL to convey concepts are purely physical. Along with the signs, your expressions, energy and the space around you are all used to communicate meaning. A question is asked by furrowing your eyebrows. The past is literally behind you and the future in front, and instead of using tenses to indicate when something happened, you place it along this invisible spacial timeline. I was a beginner to these concepts, an outsider to the culture, and even if I could have written in a way that would capture the language, I wouldn’t have done it justice. There are limits to words. ASL expresses emotion and meaning in ways that English cannot … I found myself wishing that I could abandon the written word completely. Many concepts felt more alive in ASL. I excavated my own writing in a way I never had before, and my script had become a fluid, breathing thing.

Learning to fish

This search for authenticity had another dimension too. The townspeople had already worked on Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester By The Sea (2016), so Heder had the benefit of access to key people, while everyone understood the strange eruptions of a film crew in public spaces. Locals provided a lot of help, added details, volunteered as extras. Key Deaf people were taught fishing and fish-handling skills till the routines were second nature. It was a gift of knowledge, part of the way that art can be embedded in life.

CODA has been a howling industry success with its awards, a raft of YouTube clips with the actors, the director and various experts. Apple bought it for AU$44m. I wasn’t completely entranced but it deserves the Oscar as a tribute to its process, which makes an enormous difference to the experience of the film. We honour a particular kind of artistic fire.

To me, authenticity is a fundamental idea, though its actual meaning depends on craft and context. It is about truths that we inhabit, that are ourselves. It is bound up with honesty and trust, with identification and safety and surprise. I believe that a crusade for authenticity reinvigorates exhausted art forms, and blows away cliches. It is the antidote to numbness and boredom. It attacks the zombie conformity that stops us from thinking.

In our massive experiment with inclusion and diversity which is roiling around at the moment, we are making mistakes, and magic gains. The right to participate in our culture’s stories is fundamental and makes a huge difference to lives which are so easily marginalised.

I am sometimes shocked by the difference that my hearing impairment has made to my life and I wonder who I would be if I didn’t strain to hear. I miss information, I don’t know what is going on, I don’t know who is in the room, I lose things because I can’t hear them fall.

I am hopeless picking my way through a crowd because I can’t hear where you all are. There are lots of comic details, like I can’t hear the feedback screeching of my own hearing aids, what I hear rhymes with what you said, I race around rooms looking for phones, I don’t always know if I am shouting.

The power of difference

This all leads to the point of this personal moment. I know I am different, a bit eccentric, lovable but sometimes strange. I feel there is something bent about me from the world’s point of view. But at the same time I am interesting, I have a point of view which makes the world creak ever so slightly as I articulate what comes from my hearing and seeing.

I think that is the point of me in our world. It is a kind of freedom and ultimately a skill, and a gift. You wouldn’t read me if I didn’t write like this, but then I wouldn’t write like this if I wasn’t hearing-impaired. I suspect I would have spent my life in radio, with that special relationship with sound and the sound of words. It’s not a big deal because I like my life and my impairment is pretty minor.

But this is why people who ‘live with a disability’ can enrich your lives if you have the eyes to see, the ears to hear and the feet to dance.