Warning: the following article includes references to suicide and mental illness.

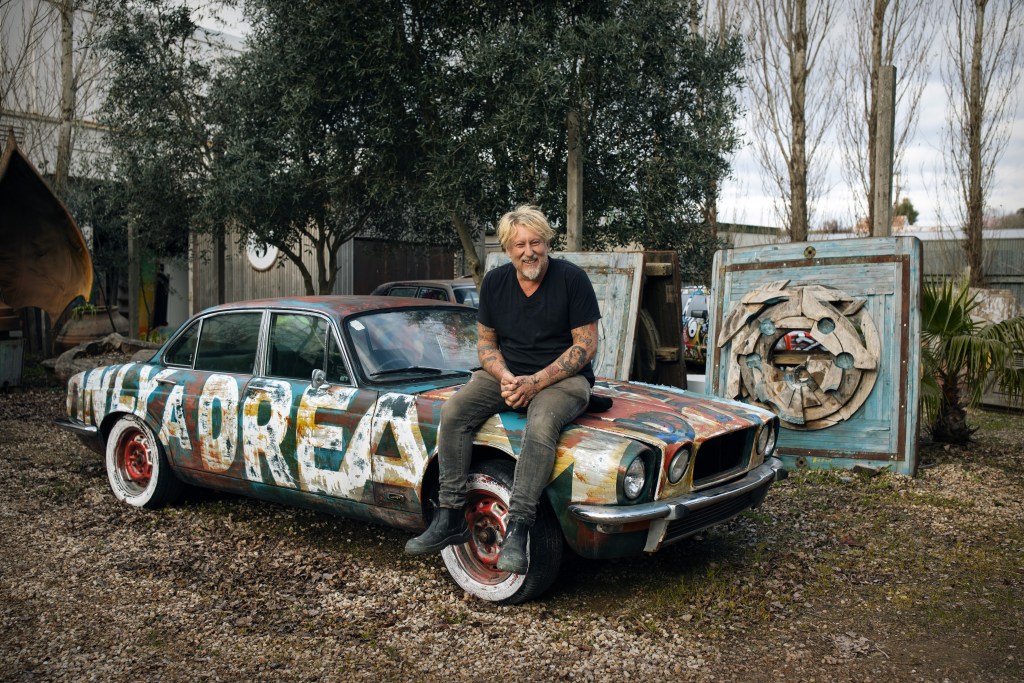

David Bromley is one of Australia’s most renowned artists. His striking female nudes are immediately recognisable and he has been an Archibald finalist six times. Bromley’s career is the subject of Melbourne-based director, Sean McDonald’s film, Bromley: Light After Dark.

Bromley says he was apprehensive about committing to the project. Bromley: Light After Dark is the first documentary in which he has participated, throughout his nearly 40-year career.

Yet, when he and partner Yuge Bromley, met McDonald, they immediately knew they wanted to be a part of the film.

‘We fell in love with Sean, Yuge and I,’ Bromley tells Artshub via Zoom from the Gold Coast, following a screening of the film.

Filmed over five years, the film examines Bromley’s life and work, as well as his mental battles, phobias and suicide attempts. In it, Bromley who is bipolar, candidly goes into detail on his lifelong mental health challenges and suicide attempts.

Balancing these elements was ‘extremely challenging’ for McDonald.

Bromley’s struggles and mental phobias began in his adolescence. Born in Sheffield, England in 1960, he moved to Australia at the age of four and was raised in Adelaide. He left school at 14, around the time his mental health struggles first started appearing and he began experiencing agoraphobia, anxiety attacks and a fear of flying.

Bromley made his first suicide attempt at 23, which he graphically describes. He made another at 33.

‘I was so violent towards myself sometimes, because I desperately did not want to live a life of quiet desperation,’ he says.

After drifting around for several years, Bromley moved to Noosa in his 20s, where he lived in a caravan and started surfing as a way to deal with his struggles. It was while Bromley was living there that he attended an artisan market in Eumundi and took up pottery, marking his first foray into art. A few years later, painting followed. Over his career, he has exhibited in Tokyo, Paris, Singapore and London. He has painted portraits of Kylie Minogue and Kate Waterhouse, though a career in art was something he never conceived of when he was younger.

Much like the documentary, Bromley talks with extraordinary openness about his incredibly difficult experiences.

‘My father always used to say to me, “If you try and kick yourself again, come and get me, because I couldn’t bear you not being around”,’ he recalls.

Despite the extremely sensitive territory, Bromley says he had no qualms about being open on his past, which he considers a necessity. Both he and McDonald were conscious of not shying away from his struggles.

‘Our 10-year-old heard for the first time that I tried to kill myself twice at the screening in Western Australia,’ Bromley says.

I think living openly and being who you are is part of my schtick, to some degree. And it is a way of demystifying [mental health]. I do believe the truth will set you free,’ he adds.

For McDonald, focusing on this aspect was extremely important.

Read: Mental health is a human right: we’re talking about a revolution

Another subject Bromley: Light After Dark tackles is Bromley’s controversial commercialism, as well as his almost industrial output. In the past the artist has drawn criticism for his blatantly commercial approach. In 2018 he teamed up with Vegemite to design a label for its 95th anniversary, which he said was an honour. His other commissions include a line of perfumes for Chemist Warehouse, wine labels for Wolf Blass and artwork for Heston Blumenthal’s Crown restaurant. Bromley has also produced coffee tables, chairs, mugs, as well as tableware with Robert Gordon.

In the documentary, Melbourne art critic Mark Holsworth draws attention to Bromley’s sheer commercialism. Yet, the outspoken Bromley says he cares little about what his critics think.

‘I simply have a feeling that a controlled artist is just the antithesis of art,’ he says.

When Bromley decided he wanted to defy the expectations imposed upon him, and branch out into pottery, print-making and design, he faced significant pushback from the art world for going against convention, and was effectively ousted.

‘I just do not think it is the way for an artist to do what they’re supposed to do. You cannot please everyone all the time,’ he says.

Another key aspect of the documentary is his creative partnership with his wife Yuge, a former lawyer and fashion designer. The two have been together for 13 years and have three children. Bromley credits her with having an enormous influence on his approach to work and life. She says a key to what makes their relationship work is that they are equal partners and collaborators in life and in their work.

‘David and I, especially over the last 10 years, we’ve almost become telepathic in some ways in how we communicate,’ says Yuge. ‘I think a lot of people assume that David takes a very creative role, and I probably take more of the business admin role, which is, I’d say, maybe 60% true.’

Opening the conversation

Bromley says he hopes Light After Dark helps start more conversations regarding openness on mental health.

‘I’ve got a fair few fairly masculine friends and friends of bikers and stuff like that. And it’s amazing how 80 or 90% of them said, “Man, this is just so needed for us, to be able to have this voice”.

‘Should [mental health] be talked about? Yes. the person who has these things should do everything in their possible power to, not just talk about it, but to do something about it. I’ve already done my laps. There are many, many different things that I try to give everyone around me the love that they deserve and the care they deserve, and to not make it about me. [It’s important to] do everything you possibly can not to weigh too heavily on the people around you,’ he adds.

Talking about mental health prompts an openness about the topic, he believes and Yuge agrees.

‘Actually, I’ve found even through feedback from some audience members, I think what it opens up is a discussion of just life,’ she says. ‘We’ve had mothers and daughters come up to us go, “We need to talk about our relationship more, how we interact with one another. What are the ways we communicate with one another? And perhaps let’s all be a bit kinder in how we talk and maybe a bit more open about how we talk, whether it’s in relation to your emotions or just how we get along.” And that’s what I really love about the film, really.’

Read: Contemporary art in historic sites: why do we love them?

‘It’s opening a conversation about, well, if my life’s crumbling in and there are things that are really taking me down mentally, how do I start to climb that ladder out? And what things can I put in place?’ concludes Sean McDonald.

Bromley: Light After Dark is in cinemas Thursday 16 November.