Did the world really need another acronym? If we take the recent rapid rise in conversations around NFTs – then yes. Non-Fungible Tokens (or NFT) are simply a form of cryptocurrency. For many of us that might already be a stumbling block.

Keeping it simple, writer Paul Ennis explains an ‘…NFT artwork is made up of two things. First, a piece of art, usually digital, but sometimes physical. Second there is a digital token representing the art, also created by the artist.’ Essentially they are collectable, and tradable.

You might be asking then, ‘Am I missing an opportunity here?’

Let’s take a look at how you can join the trend, the pros and cons, and whether NFTs offer a career advantage?

1. Market value, or devaluing

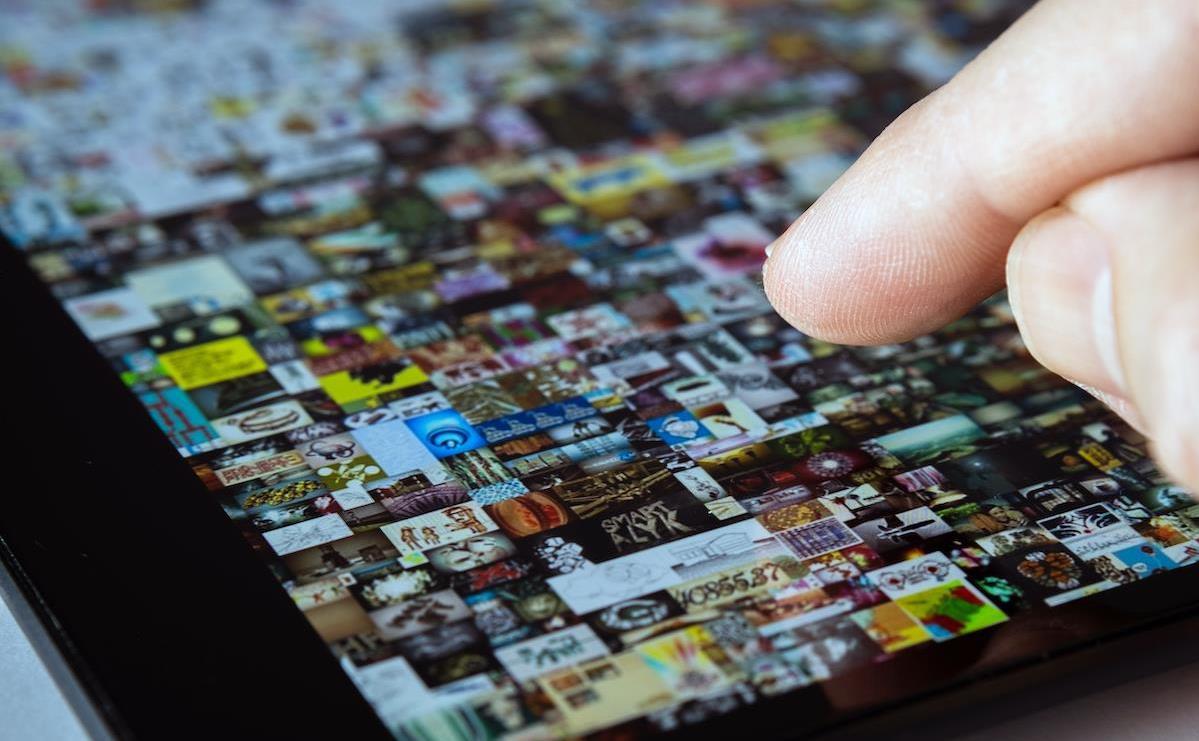

Reports of Christie’s auction house selling the work The First 5000 Days, created by Beeple (a 41-year-old illustrator from Wisconsin, USA) for $US69 million (3 March) was a wake-up call for the arts sector.

It was a collage of 5,000 images or software-drawn pictures by illustrator Mike Winkelmann, who has posted an image online every day since 2007.

It was the first completely digital NFT sold by the 246-year-old auction house who took their first plunge last year with an NFT by British artist Robert Alice, which was paired with a physical work.

Pros: The upside of blockchain and cryptocurrencies is that it is a decentralised marketplace, and that the buyers are largely independent of the traditional art market as we know it. It means that there is a potential market for your work outside of cliquish circles of art dealers and art advisors.

All would argue that Beeple’s digital collage would never have sold for that value through the ‘traditional commercial gallery’ route.

‘The money coming into the space is money that was already in the space … Crypto people are buying NFTs,’ said Kevin McCoy in 2014, the artist thought to have created the first NFT.

Cons: While the crypto economy thrives on utopian rhetoric about freedom and democratisation, in reality it is for all.

Blockchain-fluent artist and developer Addie Wagenknecht says that the underlying technology is complicated for a layperson to understand, let alone use on their own.

She described NTFs as ‘a feedback loop fixated on Silicon Valley idolatry’.

‘Facebook won because learning to host your own sites, chat clients and blogs was too much work. So what is happening is the same people who disrupted banking or technology or the web in the Valley are now claiming that they have changed the world again, when really it’s just the same people making the same stuff for the same people to get rich from,’ Wagenknecht told Artnet,

It was a warning that Wellington-based artist Pepper Raccoon told The Big Idea, ‘When you’re sold on the idea that your work has imaginary value – virtual value on the internet – someone is gaining from that. It’s important to look at where the money is actually going.’

On top of that, there is a simple flaw also to be accounted for. The indie band Kings of Leon got great global press when it released its latest album as an NFT last month at just $50. But what it didn’t account for were ‘gas fees’ – what Kenny Schachter’s describes as real-time cost of transactions based on supply and demand, like credit card fees charged to vendors’ in his glossary of NFT terms.

The fees amounted to $70, and the band had less sales than expected, so a few weeks down the track it is being notched up as a ‘marketing exercise’.

2. The Environment

Cons: Many have warned in the recent months, that the platform on which NFTs sit – the Ethereum blockchain – is outdated and unable to adapt to the increasing volume adopting the medium.

The greater peril however, is the energy consumption required to mine Bitcoin and Ethereum. Some reports liken it to the annual carbon emissions of Aotearoa New Zealand or Ecuador, and is on track at this growth rate to parallel London’s energy consumption.

As artists do you want to fuel that with your art?

Pros: One pro is that this work is usually done from home, so while blowing out energy consumption, the flipside is that travel costs and office rental are reduced in terms of their green footprint.

One positive resource to help arm you with information before diving in is the recently published, A Guide to Eco-Friendly Crypto Art, that helps you get started ‘the greener way’.

Image Shutterstock

Image Shutterstock

3. Authentication, ownership and provenance

Earlier this month the blockchain company Injective Protocol burnt a Banksy screenprint it had purchased, and effectively turned it into a new blockchain art.

They argued that the live-streamed burning on the Twitter account BurntBanksy was ‘more valuable’ than the original screenprint.

This raises all sorts of questions for the arts sector from authenticity, conservation, market impact, tax and resale implications, and plain old authorship and copyright.

Pros: The big pro is that blockchain is super safe. Because blockchain is a network, rather than a central authority, you can trust the system without having to trust any individual contributor.

‘Once data is “on-chain,” it cannot be deleted … This means each NFT’s scarcity and provenance are secure, which in turn amplifies demand, which in turn builds a more confident, more robust market than we’re used to seeing for digital artworks without blockchain backing,’ says market writer Tim Schneider.

In the case of the burnt Banksy, the value of the physical piece has effectively been moved onto the NFT, and the smart contract ability of the blockchain (conditions and details are coded into it), will ensure that no one can alter the piece.

And for NFT fans, it is considered as the true piece that ‘exists’ in the world – not a stand-in – and hence is authentic and original in its own right.

Cons: While that might be the case, others have suggested that art theft is a growing concern with NFTs.

‘Over the past few months, stories have emerged of artists discovering their work in online marketplaces, where they’re sold as NFTs without their consent,’ says Raccoon.

‘The value proposition of NFTs is that the proof of work ensures your original piece has a unique token attached to it, which means that the person who owns it knows that they have the ‘original’. But the problem is that someone can take a JPG and throw it up on a different marketplace, with a different token attached to it and sell it. There is no ‘original’.’

Read: Are NFTs already on the nose?

4. Smart Contracts

Pros: NFTs become fascinating when it comes to contracts – more specifically ‘smart contracts’ as they are being called.

In a nutshell, the “smart contract” is a set of commands on the blockchain that are executed without human intervention, and meet certain verifiable conditions.

What this means is that an NFT artist can ensure they get a cut in resale royalties – a percentage set into the terms of the sale. While Australia has an active Resale Royalties Scheme, in the UK royalties are capped at €12,500, while in the US there is effectively no scheme. So for a global marketplace – which art occupies – this is a big win.

Further, as Amy Whitaker, a professor of visual arts administration at New York University who began researching blockchain in 2014, explains, that benefit is perpetual as NFT artworks circulate through the marketplace over time.

Copyright Agency’s newsletter recently tackled the topic from an Australian perspective. The peak organisation is responsible for managing our resale royalty scheme.

They revisited their review of blockchain and how it might assist in the management of the Resale Royalty Right from an Australian perspective, using their existing case study with Desart and their Digital Labelling Project.

‘To test and build our understanding of blockchain, we developed an application on the Ethereum blockchain. Having completed our research and built a test visual arts blockchain, we found that blockchain technology is well developed and functioning effectively for digital uses like Bitcoin,’ said Copyright Agency.

‘In visual arts rights management, it can offer automation and efficiency; however, this needs more development in ensuring data integrity for physical works onto the blockchain. There are some very effective methods for uniquely tagging physical works, but more needs to be done on the associated business practices to ensure accuracy,’ they added.

Cons: Artists tend to use the standard Ethereum smart contract (known as ERC-721), which currently has no resale redistribution component, with each platform dictating its own resale royalty limits. So if you want to cover yourself and reap on the resale then you have to get a contract drawn up by a tech lawyer.

And at the end of the day, we are not entirely sure how enforceable smart contracts are (in an off line court) – there have been no case studies to date.

There are also concerns that haven’t been tested, in the case where an artist finds their work appropriated into an NFT without their authorisation, and the capacity of the smart contract to protect the NFT maker, rather than the artist.

5. Permanence and conservation

Pros: There are two positives built into NFTs. One is that the blockchain (which it sits on) contains the work’s complete provenance and copyright details, with the potential to add a wide range of additional information. It will always sit there in the code and not be separated from the NFT artwork.

Furthermore, in terms of provenance – a tetchy topic in our 21st Century where colonialist collecting practices are questioned and art theft is on the rise – an NFT’s full transaction history can be audited all the way back to its minting.

This means that a claim to ownership and authenticity is proven ‘on-chain’.

Cons: Artnet’s Tim Schneider makes the very valid point however. ‘Glossed over in most descriptions of NFTs is a crucial fact: what lives on the blockchain is data describing and tracking the asset, not necessarily the asset itself. Remember, the token is basically just an inventory number. It links to an artwork, but … “the vast majority” of cases, the artwork is hosted off-chain somewhere else.’

Schneider believes that rather than concrete, this setup opens up a ‘horde of uncertainties about ownership, copyright and preservation … For example, if an animated GIF is actually stored on a server controlled by the marketplace where you acquired its NFT, do you own the GIF… or just a license to access it?’

And while the idea might be permanent and revolutionary, websites often succumb to time maintenance. How many times have you got a 404 error on a no longer existing webpage. So what happens if the NFT marketplace goes out of business – does your NFT and its value evaporate?

Like any elevator pitch, there is a lot more to the sell to get an idea across the line. And while NFTs are having a huge impact, bespoke questions for their art world application are starting to arise.

Will this just mean a case of ironing out the wrinkles like any new product, or could this round peg not be the fit it was first thought to be for an alternate art market. Only time will tell.