Written and directed by David Cronenberg, Cosmopolis is a welcome return to the director’s more edgy, subversive explorations of narrative drama. The film has a ‘high culture’ origin in the eponymous 2003 novel by Don DeLillo, but in terms of Cronenberg’s oeuvre so far, the film is most strongly reminiscent of his provocative adaptation of JG Ballard’s 1973 novel, Crash.

Cronenberg’s Crash (1996) was a surprisingly faithful adaptation of Ballard’s anerotic, rebarbative novel, and while it clearly deserved the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, at the time of its release the reaction by the public and reviewers was often frighteningly vituperative. The film has since been seen as a work of a special kind of genius – a Cronenbergian kind of genius – and is now recognized as one of the most important films of the 1990s.

A similar fate may well accompany his adaptation of Cosmopolis. Like Crash, this is an adaptation of the novel that is faithful to its origin – in terms of its narrative trajectory and thematics at least –but also adds that special je ne sais quoi that make it unmistakably a David Cronenberg film. By definition I cannot say what that je ne sais quoi is exactly, but it certainly has something to do with the fact that Cronenberg is able to draw remarkable performances from his actors who often find themselves asked to do extraordinary things (I’m thinking of James Woods inserting a throbbing videotape cassette into a vaginal wound in his stomach in Videodrome, 1983; or of Jeff Goldblum contemplating his frightful decay while looking in the mirror in The Fly, 1986).

In Cosmopolis, Cronenberg has his actors perform as if in a remake of Herzog’s Herz aus Glas (Heart of Glass, 1976), where Herzog hypnotized all his actors before they went in front of the camera. Except here they are not hypnotized – they just seem that way. All of the performers in Cosmopolis act and interrelate as if we are observing a coterie of somnambulists, or perhaps, to invoke a more contemporary cinematographic convention, a clutch of zombies. This is not to say that the performances lack the essential spark that is necessary to draw us into their roles, it’s just that the intensity of the performance is all directed inward, away from the audience; a directorial conceit that in lesser hands may very well have murdered the film at the outset. In Cronenberg’s hands this robotization of the performances signals that the characters in this film maintain their humanity only as a sort of trompe l’oeil effect, an illusion produced by the fact that they look like us, dress like us, have wives and jobs like us, but they are not us – they are part of the alien 1% who own and manipulate almost 50% of the world’s wealth.

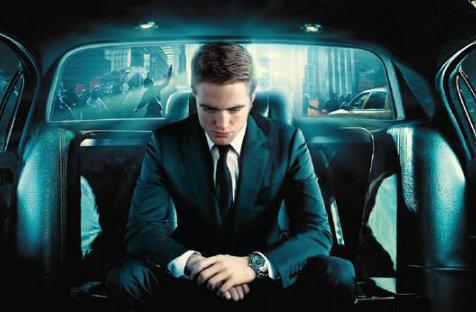

We see this from the very beginning of the film, where we find billionaire Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson of the Twilight saga, more like a vampire here than ever he was in the teen tittilators) ensconced within his stretch limo, gliding very slowly through the streets of New York. Yet the streets of New York may as well not exist, for the greater amount of the ‘action’ in Cosmopolis occurs within the confines of Packer’s high-tech limousine. Associates enter the vehicle, converse in an abstract and abstracted manner, and exit onto the streets. Parker’s relationships are with cronies, call girls and teenage tech-geniuses, all of whom shore up his rarified, Wall Street cum cyber-empire world. And all of whom seem to have the gift of the gab, which in this case is a kind of language-as-deflection rather than the sort of everyday communication that most people engage in.

So, along with the non-naturalistic performances, we also have non-naturalistic dialogue and a New York that is really only the exoskeleton for Packer’s stretch limo. This entire rarified microcosm is played out in front of us at a very leisurely pace; an oneiric rhythm produced by cinematographer Peter Suschitzky’s masterly camerawork and Ronald Sanders’ assured editing, a rhythm that encourages the viewer to identify with the ennui of the film’s protagonists and to see the world as a trifling panorama moving outside the hermetically sealed world of 21st century technology and extreme wealth.

Until, of course, this comforting rhythm is destroyed by random acts of violence, as they inevitably are – this being a David Cronenberg movie and all.

The plot of Cosmopolis is the sort of thing that easily sustains DeLillo’s novel, as ‘literary’ novels often require only the barest of narratives to sustain their literary ambitions, and it is to Cronenberg’s credit that he has seen fit not to alter the threadbare story of the novel. So here is the story, as such: billionaire Eric Packer is looking to get a haircut. Yep, that’s right. That’s the thing that drives him throughout the film. So if you are looking for a plot-driven genre piece (something which Cronenberg does exceeding well when he wants to, mind you), then you had better look to his earlier films. Except for Crash, because Crash has similar ambitions to this film.

Which brings me back to how I began this review. On a formal level, Cosmopolis most closely resembles the mannered narrative explorations of Cronenberg’s adaptation of Ballard’s Crash. Yet Cosmopolis is also distinct in terms of its ‘voice’, as it were. Cronenberg’s A History of Violence (2005) was his damning evaluation of the Bush administration years (don’t take my word for it, he said so himself), and Cosmopolis seems to be another foray into this more ‘politicized’ cinematographic territory. Just as in A History of Violence, wherein there are no senators, no politicians or political events described, in Cosmopolis Cronenberg has produced an unstinting political analysis of contemporary Amerika (with Don DeLillo’s help, naturally), without the word politics being uttered even once during the film.

Of course, the very manner in which Cronenberg has chosen to do this may well be his downfall in terms of the box office. Despite his reputation for excess, and his early back catalogue of over-the-top films, Cronenberg is an assured and often a subtle filmmaker. He is one of the last masters of the ‘classical’ Hollywood film style, even as he tries to subvert it from within: Hollywood’s classical moral certainties turned on their heads and twisted sideways, and all within a formally precise Hollywood structure.

So: on a formal level Cosmopolis is stunning. The cinematography, set and sound design are brilliant, and Howard Shore’s soundtrack is (almost) as daring as his soundtrack for Crash. The performances (Robert Pattinson, Juliette Binoche, Samantha Morton, Paul Giamatti, just to name the big names) are all exceptional, even if, as I say, they all appear to be somnambulists floating through a long talk-fest.

All of this may appear to be just a bit too precious for some, an expensive experiment that will leave many unaffected and perhaps hopelessly baffled. For this reviewer however Cosmopolis is a worthy addition to an already impressive body of work that is as unique as it is essential viewing.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Cosmopolis

Written and Directed by David Cronenberg

Canada/France/Portugal/Italy, 2012, 109 mins

Available on DVD and Blu-ray from 19 December

Icon Film Distribution

Rated MA

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: