Baz Luhrmann’s postmodern production of William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet is returning to cinemas for its 25th anniversary. Boy, does that make me feel old – but the greatest thing about this film is that it also makes me feel young.

The second in Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Red Curtain Trilogy’ bookended by Strictly Ballroom and Moulin Rouge, Romeo + Juliet may still be his best film. It remains bursting with baroque visual wit, updating Shakespeare’s text with a recognisable set of contemporary references that read as intuitive rather than corny. But nor is it bogged down in its own metatextual cleverness and bombast, as Luhrmann’s later films would be. Here, Luhrmann’s style simply defibrillates Shakespeare’s text.

And the reason why it still works is that even its vulgarities – its oversaturated colour palette, over-the-top acting, swooping camera movements and smash cuts – are vulgar in an earnest, youthful way. They work because they’re what a teenager thinks should work. Everything in Romeo + Juliet is working towards the themes of the adolescent ‘story of … woe’ it tells.

Here, Luhrmann’s style simply defibrillates Shakespeare’s text.

Likewise, its young cast are not attractive in a nostalgic way – sentimentalised from the outside, for adults to reminisce about once being young. No, they are attractive to teenagers now, in a way that drew young people back to cinemas again and again, that supercharged Leonardo DiCaprio’s heartthrob career, sold millions of soundtrack albums and powered a thousand GIFs.

DiCaprio never looked more androgynously beautiful onscreen than he does here – an erotic avatar for baby butches and femmes alike – while 16-year-old Claire Danes is incandescent with innocence. This Romeo, this Juliet, make young hearts run free because they dwell in a perennial present: playful and careless, propelled by their big feelings. The film’s pacing shares their exuberant, reckless forward momentum.

Read: News in Brief: Three Australian films to SXSW, ACMI opens up and conferences get set to go

And what struck me most when I first saw it was how unselfconsciously the young actors handle the Shakespearean dialogue. Danes speaks her lines as if her thoughts are only just occurring to her. And the young Montague and Capulet boys spit rhyming couplets at a rapid-fire pace, with the swagger of all teenage slang.

However, this naturalism was hard-won: Harold Perrineau, this production’s wickedly exuberant, genderfluid Mercutio, recalled in an interview last year, ‘I struggled to make it sound natural. … I said the words over and over, but to make them real, and original to me, that took the longest.’

Another creative choice that seems shrewd in retrospect is the way Luhrmann presents the peripheral characters, so as to enhance the naturalism of the central characters. Miriam Margolyes copped a lot of flak at the time for her burlesque Nurse, who spends a lot of her screen time running around shouting, ‘Hooliet! Hooliet!’ But she’s a foil to Danes, serene and purposeful beside her. Similarly, Diane Venora is all brittle gurning and peacocking as Juliet’s mum, Gloria Capulet – but this only underlines the generational gulf between her and her daughter. And a baby-faced Paul Rudd is nothing short of the perfect doofus as Juliet’s unwanted bridegroom, Dave Paris – it’s obvious why he’s perfect on paper, but completely disconnected from Juliet.

By contrast, it’s clear why Pete Postlethwaite’s Friar Laurence is a confidante to Romeo: Luhrmann chooses to portray him as a more sympathetic generational link. Laurence is a mellowed-out Boomer hippie with a Celtic crucifix back tattoo, whose fondness for botany is played as countercultural cool rather than monkish scholarship. Lawrence hides his Hawaiian shirt – that visual link to the Montagues – beneath his priestly cassock, like the loyalty he conceals in the name of religious neutrality. And it’s one of the film’s nice touches that baby Leonardo wears the same shirt so well – this symbol of intergenerational connection has become one of the film’s iconic costumes.

When I studied Romeo and Juliet in year 10 English, we watched the Boomers’ version: Franco Zeffirelli’s luscious 1968 film, which was wildly acclaimed and mildly scandalous at the time for its nude scenes involving 17-year-old Leonard Whiting and 15-year-old Olivia Hussey. Compared to George Cukor’s painstakingly theatrical 1936 adaptation, this was a fresh new Romeo and Juliet for the counterculture generation. (However, lightning did not strike twice for Zeffirelli, whose next story of teenage erotic tragedy, 1981’s Endless Love, was critically savaged.)

Over the past 25 years, Baz Luhrmann’s film has replaced Zeffirelli’s in schools as teenagers’ first visual encounter with this text. And the very things that older critics disliked about it on its release – its melodramatic performances; the hyperactive editing by Jill Bilcock; Catherine Martin’s more-is-more set decoration; the symbolism of Kym Barrett’s costumes – made it fit natively into the visual idiom of millennials, and even Generation Z.

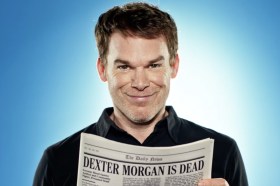

Romeo + Juliet was made with a Gen-X sensibility – or as people said back in 1996, ‘for the MTV generation’. It’s actively mediatised and anti-theatrical, from the framing device of TV newscasts and newspaper headlines to the way Romeo is introduced, moping at dawn, by the crumbling proscenium of a derelict theatre. And Luhrmann’s decision to shoot in Mexico City as the fictional Verona Beach (which seems part Miami and part Venice Beach) folds the play’s Italian dynastic warfare into the grimy visual language of 1970s and 1980s American crime storytelling – Scarface, Miami Vice, To Live and Die in LA.

the very things that older critics disliked about it on its release … made it fit natively into the visual idiom of millennials, and even Generation Z.

Verona Beach also operates thematically as any number of real-life ‘divided cities’ that the film’s original 1996 audience would have known best through mediatised depictions of violence in news coverage – Berlin, Belfast, Beirut and more. This is a racially fraught hot zone where the (Irish?) white-coded Montagues, led by bluff Brian Dennehy, face off against the Latino Capulets, led by fiery Paul Sorvino.

Even the film’s Catholic imagery reflects the postmodern mediatisation of religious iconography at the time, from Madonna’s ‘Like A Prayer’ music video to the sacred/profane homoerotic art of Pierre et Gilles. Everyone who’s seen the film remembers Juliet’s angel costume, the looming Christ statue – its homage to Rio’s Christ the Redeemer monument – and the final death scene in a cathedral filled with candles and neon crosses. But only on re-watching did I realise just how much more Catholic kitsch is packed in here. Juliet has her home altar with an icon of the Virgin Mary, who also appears in a gigantic painting on the landing of the Capulets’ home staircase. Tybalt’s leather vest also carries an image of the Virgin.

There’s a strong Gen-X cynicism about religion in this film – like Friar Laurence’s cassock, it’s something you put on and take off when it suits. Its morality has been hollowed out so it has become just as much a weapon against young people as the Sword-brand guns brandished by sensation-seeking gangs. Even the way the final sequence is staged suggests that Romeo and Juliet have sacrificed themselves needlessly on the altar of their families’ pointless feud.

And that soundtrack – the one that was in everyone’s CD collection, and that’s playing through my laptop speaker as I write this – has more than just pastiche, such as the soaring vocals of Quindon Tarver singing ‘When Doves Cry’ and ‘Everybody’s Free (To Feel Good)’. For every sweet, euphoric high – Candi Staton’s ‘Young Hearts Run Free’, the Wannadies’ ‘You and Me Song’, or the Cardigans’ ‘Lovefool’ – there’s also a kind of alienated angst that now reads as incredibly ’90s. Shirley Manson sets the scene with her deadpan delivery of ‘I would die for you’ on Garbage’s ‘#1 Crush’, while Romeo is introduced moping to Thom Yorke’s keening on Radiohead’s ‘Talk Show Host’.

Read: TV Review: Bump is Australia’s answer to Booksmart

Younger audiences have been quick to memefy the film’s more straightforwardly romantic imagery, like angel-Juliet dreaming on her balcony, the fish-tank meet-cute to Des’ree’s ‘Kissing You’, knight-Romeo kissing angel-Juliet, or the baptismal immersion of the lovers in swimming pools and pure-white bedsheets. Even the queer-coded imagery that has been celebrated by younger viewers – specifically between Mercutio and Romeo – wasn’t a new reading of Shakespeare’s text, but was only yanked to the foreground in Luhrmann’s telling.

For me, it’s the overblown carnality that makes it such a perfect adaptation of the source material, and that still leaps from the screen today. Jokes about a courier company called ‘Post-Haste’ aside, Luhrmann really doesn’t over-intellectualise the material – he lets us feel our way through the film as its characters do. This is a film about unruly, disobedient young bodies – and one of the delightful things about cinema is that while we will always age, it captures that freshness of youth forever.

To mark its 25th anniversary, Romeo + Juliet is being rereleased in selected cinemas – just in time for Valentine’s Day.