The death of David Lightfoot caught industry people by surprise. He lived mostly in Adelaide which is a little removed from the major centres of production companies, while the social connections of the industry were cut back by Covid. He had the ability to create intense connections which are now replaced by bewilderment and grief.

He was known as a loyal friend, capable of strong emotions, with a slightly different way of looking at problems. According to producing colleague Tania Chambers, ‘He was just so open with emerging filmmakers, and trying to get their talent to the attention of the right people. It was never too much for him to do budgets on spec, and work out how to make the impossible possible.’

‘What a great guy he was, and what an excellent career he had,’ said Antony I. Ginnane, who worked with him over the last few years. ‘He masterfully managed films which were low budget and difficult to make and he did them with total respect for the vision of the director. He was terribly loyal to a small group of people he worked with again and again, and he inspired total loyalty in his friends.’

He entered the industry in the 1980s after he left the army, to effectively sweep the floors at the South Australian Film Corporation when Head of Sound Michael Rowan and gun sound mixer James Currie rebuilt the mixing studio. Lightfoot brought his practical and organisational skills to bear as a location manager on films like Golden Fiddles, Dingo, Hammers Over the Anvil, the TV series The New Adventures of Black Beauty, and Babe, where he shared the credit with Peter Lawless.

From the beginning he felt very strongly about veterans’ issues and the neglect of PTSD. According to Ginnane, ‘He was a typical Australian, with a respect for the army and he loved his football, but he was terribly devoted to film.’

By the mid-1990s he was a first assistant director on The Quiet Room, The Idiot Box, Lust and Revenge and Spank. He worked his way up to producing for himself through Richard Flanagan’s One Hand Clapping, where he was co-producer to Rolf de Heer as producer, then Franco di Chiero’s Three Together where he produced with Jane Ballantine, and then Ernie Clark’s Spank which he co-wrote and produced himself with Rolf de Heer as executive producer.

From 2000 he was often a line producer on films like Japanese Story, produced by Sue Maslin with Sue Brooks and Alison Tilson as co-producers, Love is Now with Behren Schulz as producer, and A Few Less Men, where he worked with Tania Chambers around 2017.

His first clear producing credit came with low budget horror film Coffin Rock, which he produced with Ayisha Davies in 2009.

He worked on the iconic horror film Wolf Creek as producer/line producer, with Greg McLean as producer and Matt Hearn as co-producer / executive producer. On Rogue two years later, he was producer with McLean and Hearn.

He went on to produce John Doe: Vigilante, with James and Kirsty Vernon and Keith Sweitzer. Most recently he produced Bad Blood and Never Too Late with Tony Ginnane (p.g.a).

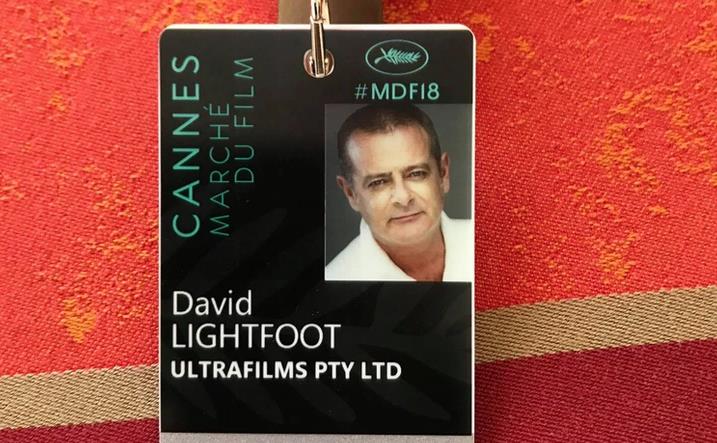

As the message on the Facebook page for his production company Ultrafilms says, ‘David dedicated his life to the film industry, and was passionate about Australian film and telling Australian stories. Ultrafilms has a number of projects underway and will continue its future slate under the direction of David’s business partner and Co Producer Sabella Sugar’.

Many people cared for him as you will see from the comments.

David Lightfoot had a particular kind of role in the Australia screen sector. He mostly worked in film and brought a range of practical skills and South Australian knowledge which was important in attracting productions to the state. In return he worked with a variety of producers who gave him skills and encouragement to develop his own career. The unpretentious tightly budgeted commercial films he worked on are a vital part of the sector. Ironically, the growth of the streaming companies promises to open opportunities in just that sector to which he gave such persistence and energy.

He was a raconteur, hilarious at Cannes and famous for his cream tuxedo. You can’t work in his space without incurable optimism and all the abilities to get the details right.

According to Ginnane, who is very aware of screen history, ‘In some ways, David didn’t fully get the recognition he deserved, despite working with people like Rolf de Heer and Greg McLean. Perhaps his position as a creative as well as a line producer could have been respected more. History will write that story. It is just a tragedy that he was taken from us at such a young age.’

He was in his early sixties. It seems his funeral will be private, but there will be a larger wake for him in Melbourne once travel is normal again.