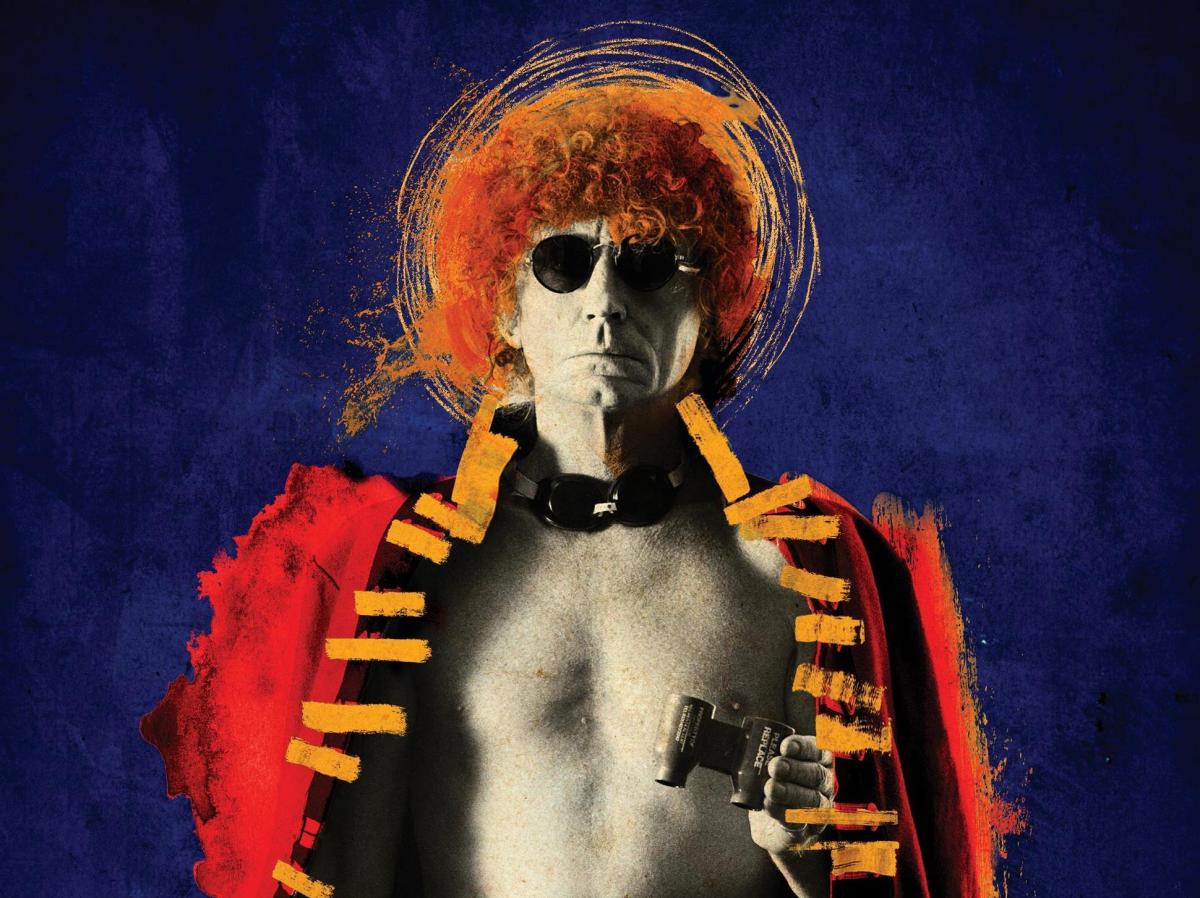

Whiteley poster image via Transmission Films.

In 1978 Brett Whiteley won every major Australian art prize: the Archibald (his second), the Sulman and the Wynne, the only time all three prizes have ever gone to the same artist. An introductory scene of the film Whiteley takes place at a Sotheby’s auction where a painting of the Sydney Opera house sells for $2.8 million, in case you didn’t already know of his significance. There’s a nice coincidence in the fact that the film Whiteley opens in Melbourne shortly after the van Gogh exhibition opens at the National Gallery of Victoria – Vincent van Gogh was Brett Whiteley’s early, complete, inspiration – as you hear from him, Whiteley was a schoolboy when he found a book about van Gogh lying on the floor in church. Whiteley didn’t come from a cultured background and was hitherto unaware of van Gogh. The youngster was so affected by the images that he knew then, instantly and irrevocably, that he would dedicate his life to painting. How chuffed Vincent would be to know this, if only he could.

Brett Whiteley’s life exists in the public’s imagination at the level of myth, and, these days, of cliché: the all-consuming talent, the great love, life lived in extremis through the creative drive, debauchery, affairs, and a descent into addiction. Whiteley by James Bogle and Victor Gentile, however, is a strong, truthful and satisfying film, his story told through the words of the artist himself, Wendy Whiteley, and his sister Frannie Hopkirk. Whiteley gives you a sense of the man; you come away feeling as though you knew him.

Brett and Wendy Whiteley were amongst those who defined the West’s artistic zeitgeist of the 60s and 70s, they lived in London, and in New York at the top of The Chelsea Hotel, they knew everyone, they were glam rock gods at the pinnacle of the world’s art scene. Whiteley makes good use of abundant archival material, some not seen before. Famous Australian faces such as the writer Patrick White and the artist Michael Johnson appear throughout. Whitely was an eloquent writer and much of the pleasure of the film is hearing his words, from letters, and from radio and television interviews and earlier films (including clips featuring a young and positively bouncy Robert Hughes). With the artist’s work being so raw and personal you come to care about his struggles, even at the times when you see Whiteley himself being less-than-authentic, playing to camera.

Wendy Whiteley was only fifteen when the couple met at art school in Sydney and glued themselves together in lust and love. In many ways this is as much Wendy’s film as her husband’s. His artistic muse and power source for decades, she talks about how she eventually had to leave him to save herself. Wendy is down to earth, blunt, and, although she’s wearing a black veil in the film (an elegant nod to mourning?), she isn’t invited to, nor does she ever play, the tragic figure. Tragedy speaks for itself in the film when their daughter Arkie talks about expecting the phone call about her father’s death for months before it happened, and there’s another sad shock when you remember how she died so young in 2001.

The visuals of the film are suitably ravishing, as theatrical as the Whiteley trio were themselves, with big lingering close-ups and long views of the pictures; old photographs are animated to bring a pulse to the stories and to the moods and aesthetics of those vital four decades. …. Despite finally being eaten alive by heroin, Whiteley kept painting. As noted so often, you can see the addiction in his later work; some of his best paintings were done during his worst times. He was a committed artist always, and fearless. What was going on in his head while he painted sex, land, and life (and so much else) so extensively? ‘A bunch of violets, a grain of sand and a sledgehammer,’ is one answer. This film leaves you impressed anew with Brett Whiteley’s genius; it’s a close interrogation of an artistic life and also an exercise in nostalgia and Australian cultural history. Heartily recommended to everyone.

Rating: 4 1/2 stars out of 5

Whiteley

Filmmakers

Director: James Bogle

Writers: James Bogle, Victor Gentile

Cast

Brett Whiteley

Wendy Whiteley

Frannie Hopkirk

Genre

Documentary

.

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: