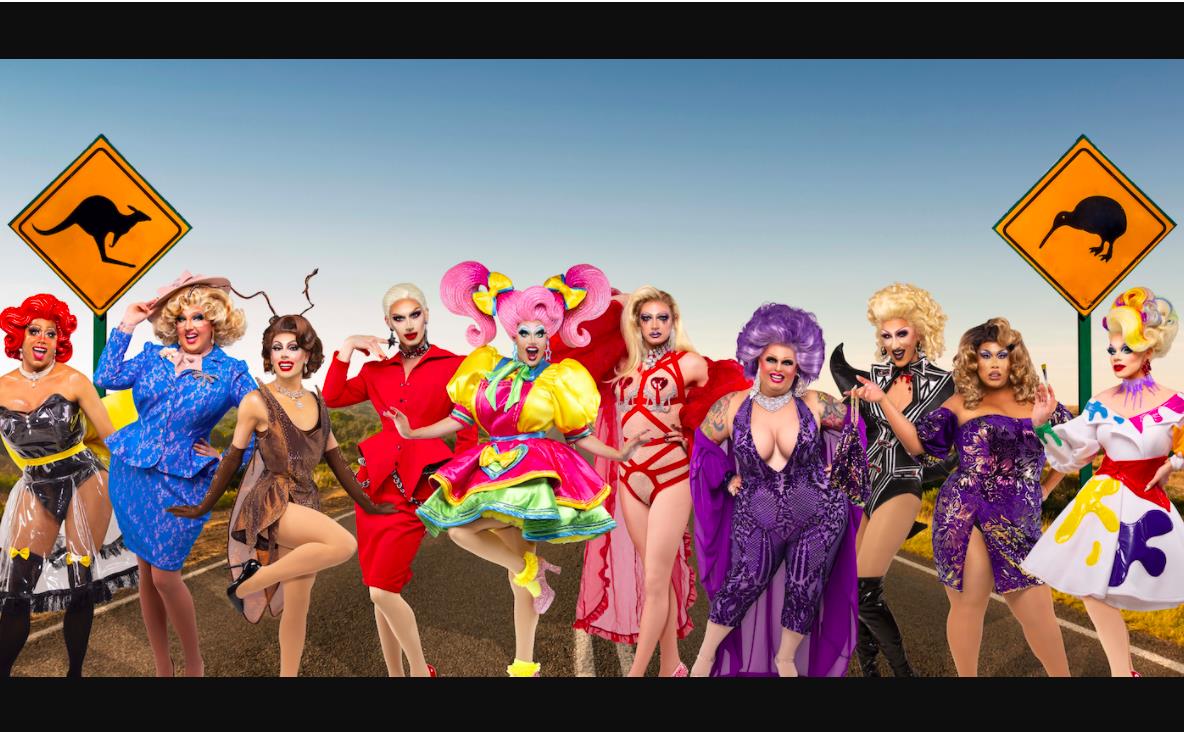

RuPaul’s Drag Race Down Under will premiere on Stan this Saturday. The Australian-New Zealand version of the global reality TV juggernaut will share an Antipodean mode of drag with audiences around the world.

Veteran drag star RuPaul created Drag Race in 2009 for niche US cable channel Logo TV. It parodies reality TV competitions such as America’s Next Top Model, with a group of drag queens competing across various performance-related challenges to be (literally) crowned the next ‘Drag Superstar’.

RuPaul has since built up a media empire. The show, which moved to the mainstream US channel VH1 in 2017, has had successful spin offs in the UK, Canada, Thailand and Holland.

Drag Race has relocated drag culture from the fringes of society, making it a legitimate art form, lifestyle, and path to celebrity. However, the show has also been critiqued for ridiculing certain ethnicities as well as for excluding trans performers. Responding to this criticism, more recently, Drag Race contestants have included trans women and (so far) one trans man.

Until now, only the US and UK versions have featured RuPaul and his “Best Judy” Michelle Visage as judges. Drag Race Down Under will also have this fierce duo on its main judging panel along with Australian comedian Rhys Nicholson. Both Australian and New Zealand drag queens will compete, with guest judges including singer Kylie Minogue and Kiwi film director Taika Waititi.

Having been accused of mainstreaming drag, eliminating its subversive impetus, it will be intriguing to see how this slick show — built on US histories of drag — approaches the Australian drag tradition.

Drag’s blokey culture

In Australia, drag queens have tended to have an ocker sensibility, which has made them perhaps surprisingly welcome within a blokey culture.

There is an important difference, however, between the queer drag that drag queens perform and straight drag. Queer drag is aligned with LGBTQ+ communities and can powerfully reject the constraints of gender norms. In contrast, straight drag usually entails heterosexual men dressing up in feminine clothing for the sake of comedy — and it can be used to mock women.

Australian screen culture reflects the place of both these forms of drag in broader Australian society.

In Australia the practice of straight drag is also associated with laddish behaviour. Certainly, the burly blokes on The Footy Show were notorious for donning women’s garb for comedy sketches.

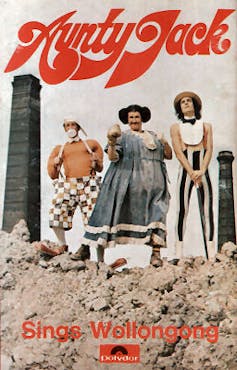

For instance, in the 1970s, the TV character Aunty Jack sported a blue velvet dress, a moustache and one golden boxing glove.

Dame Edna Everage was also born of this tradition. Played by straight cis man Barry Humphries, Edna first appeared on TV in the 1950s as a character satirising suburban Australian housewives. She went on to become a larger-than-life ‘Dame’ with sequined cat-eye glasses.

In Australia the practice of straight drag is also associated with laddish behaviour. Certainly, the burly blokes on The Footy Show were notorious for donning women’s garb for comedy sketches.

Despite stark differences between the two, queer drag and straight drag are often unusually interconnected in Australia because both feature aspects of the ocker.

While queer drag is celebrated in LGBTQ+ bars and clubs every night, straight venues around Australia — including RSLs and rural pubs — also regularly host queer drag queens.

Queer drag also looms large in Australia’s collective consciousness. Notably, in the 1960s, the queer cabaret troupe Les Girls in Sydney’s Kings Cross became a “must see” spectacle for mainstream Australia. These glamorous performers appeared to be beautiful women but were all queer men dolled up in wigs, makeup, sequins and feathers.

The most famous Les Girls showgirl was the busty “bombshell” Carlotta. In the 1970s, she also became Australia’s first transgender celebrity. Carlotta has performed drag throughout the country for more than 50 years and remains a revered queer figure.

Discussing how queer drag became so accepted in blokey Australian contexts, Carlotta has said Australian drag queens are unique because they “have that ‘ocker-ish’ sense of humour and it related to most Australians”.

Carlotta was an inspiration for the international hit film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, in which three Sydney drag queens travel through the outback on a lavender bus, performing drag in remote locales.

It presents striking juxtapositions between the queens’ elaborate, shiny costumes and the red Australian desert.

These iconic drag queens also enact a conspicuously Aussie sense of irreverent humour that is validated by the “ocker” characters around them.

For instance drag queen Bernadette is enthusiastically applauded in a rural pub of rugged blokes when she retorts to an aggressive woman:

Now listen here, you mullet. Why don’t you just light your tampon and blow your box apart, because it’s the only bang you’re ever going to get, sweetheart.

Priscilla solidified ocker drag queens as representative of an Australian brand of queer drag. Drag Race Down Under’s trailer directly invokes imagery from Priscilla, positioning the flamboyant contestants against a desert highway with a yellow road sign warning of kangaroos.

However, this new season is yet to reveal just how ocker Aussie Drag Race queens can be.![]()

Joanna McIntyre, Lecturer in Media Studies, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.