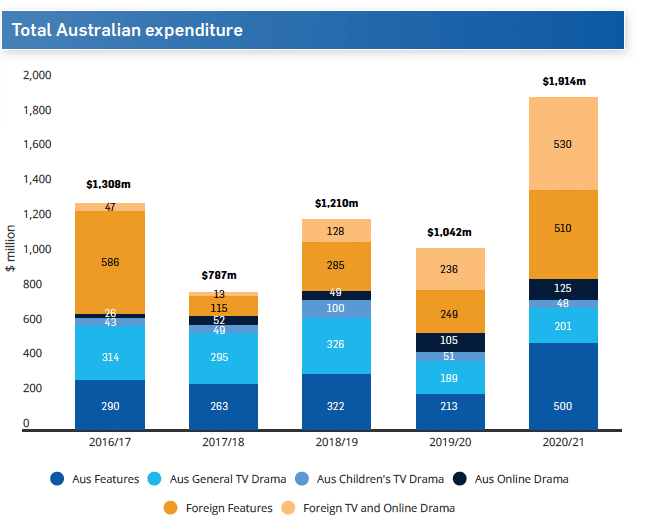

In the financial year of 2020-21, the total expenditure on drama in film, television and online hit $1.91 billion. That is an extraordinary spend, $650 million higher than any other year in the last five. The next highest is $1.308 billion in 2016-17.

That is a lot of production – covering 64 features, 23 TV dramas, 11 children’s dramas and 60 online dramas.

They are recorded in Screen Australia’s Annual Drama Report for 2020-21, which contains a list of all the productions. The budgets remain a deep secret.

Reasons for caution

According to CEO Graeme Mason, ‘We had quite a few shows pushed from 2019-20 into 20-21. On my calculation I think we had some 23 shows postponed. So that means something like $330 million was moved across.

’19-20 was on track to be a record year until COVID hit in March. Even without that, this year would still have trumped anything else.’

Read: 2020 the strangest drama report ever

These numbers use International conventions created in another era, in which expenditure is attributed to the first day of principal photography so it tells us very little about the actual amount of work at any one time. It smooths out crew shortages and obliterates cash flow issues. Screen Australia compares the annual numbers with a five year rolling average which is the best way of tracking change.

Mason also points to the increase in productions coming in from overseas, which are a mix of footloose deals and titles which are created by Australians but expected to shoot internationally.

‘So much production was brought here often by local people or companies with foreign backing because we’re a great place to film,’ he says.

That was helped along by COVID-19, as the Australian sector adapted quickly and infection figures remained low in comparison to the US.

‘A great example is Nicole Kidman and Bruna Papandrea bringing down the Liane Moriarty adaptation Nine Perfect Strangers. With three weeks notice they uplifted the whole thing that brought it to the Northern Rivers. That was because they didn’t feel comfortable that they could make it in the States but they knew they could make it here in Australia.’

the big success stories are in feature films and in streaming

Once Screen Australia peels these numbers back into the individual categories we discover the big success stories are in feature films and in streaming. Television waddles along at roughly the same pace and looks decidedly dowdy by comparison. This is a vital consideration because it points directly to policy issues.

Domestic Television

In domestic TV drama, the figure is $201 million, compared to a five year average of $265 million. There were 21 titles, down 10 on the average. In children’s television, we spent $48 million compared to an average of $58 million, for 7 titles compared to the average of 12.

The commercial broadcasters spent a total of $54 million, with Neighbours and Home and Away pumping up the hours. The ABC put in $43 million, for 17 titles, up 22% on last year while the commercials dropped 10%. The subscription TV broadcasters had nothing.

To be fair, we are living in chaotic times. Post houses have been in a frenzy of work, many productions have been stopped dead, others have worked slowly, producers have concentrated on development.

But we should note this, loud and clear: these numbers are down just as the commercial broadcasters have been effectively deregulated, and both the ABC and SBS remain sewn into their shrivelled Coalition budgets.

these numbers are down just as the commercial broadcasters have been effectively deregulated, and both the ABC and SBS remain sewn into their shrivelled Coalition budgets.

According to SPA, ‘Also of concern is that the figures reveal a significant structural adjustment in television drama, showing the lowest number of hours in the past 5 years and spend not correcting from pre-pandemic levels. SPA also notes that the full impact of the de-regulation of Australian drama on commercial free-to-air television would not yet have flowed through into this year’s report, suggesting further structural adjustment should be expected.’

However, the government has given more temporary money to Screen Australia, and raised the Tax Offset for television from 20 to 30%, all of which is useful and will soften the blow of changes. Many in the industry who face the broadcasters over desks and debate budgets are expecting the commercial sector to reduce its contribution by that 10% of extra offset on the grounds that they are suffering terribly.

We can’t cover that in detail here, but we should point out that Seven Media’s 2021 Annual Report says it had a post-tax profit of $320 million, against a loss of $200 million the year before. There are many technical reasons for this, but the numbers are certainly sturdy.

As the report points out, the total spend in the features and TV drama sector are only 30% of the total production expenditure. The other big ticket items are light entertainment, sport, news and current affairs. The return on a drama dollar is comparatively poor, so you can guess what the commercial broadcasters want to do.

That is the usual bad news – bad because the dollars earns by production companies from television drama bring much-needed stability. Generally, we have been saying that the sector is shifting from cinema to television for just that reason. It seems now that this will only work if production companies can make deals with streaming companies. All of those are by definition international except for Stan and Foxtel.

Domestic Online drama

The real change over the last five years is in online drama, aka streaming. The domestic streamers, which are basically Foxtel, Stan and ABC iView, have gone from $26 million to $125 million over this period. But the total number of titles each year remains around 25, which is a remarkably steady figure.

These figures are dodgy because they include very large and tiny productions, so Screen Australia has created a subcategory called SVOD dramas which covers the blue chip shows. There are 9 titles, which cost on average $3.3 million/hour, which is up from $2.1 million in just two years. There were 37 hours which cost $116 million, up from $34 million two years ago. You can see how the large online shows are shooting upwards.

Essentially, the spend by the streaming companies makes up for the decline in local broadcaster investment. This is a rough comparison but it is within the range of distortion created by that first day of principal photography issue.

SPA welcomes that online activity, but is quick to define it as ‘a strong and welcome indication of the potential for extensive engagement with local audiences that these platforms hold.’ That is a nod to the pressure to regulate the streamers to ensure that contribution.

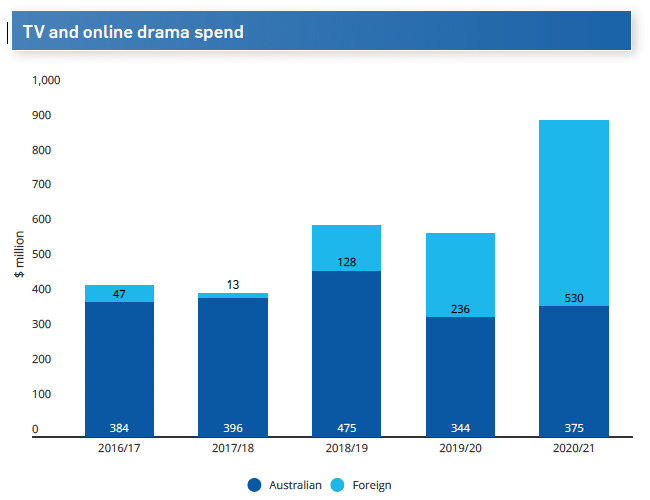

Foreign Online drama

In 2016-17 there was none commenced. The takeoff began in 2018-19 with 7 titles and $15 million in budget. In 2019-20 it rose to 15 titles and $225 million. This last year the figures were 35 and $411 million, or $11 million per project.

So the total foreign drama spend was $1.04 billion on 63 projects; two years ago it was $413 million on 41 titles. Do we sense a fundamental paradigm shift?

The larger impact

This Screen Australia graph shows you how these figures compare.

While the total domestic drama figures bumble along, the pale blue of foreign drama has grown like topsy. The growth in long form production is all global.

Feature production

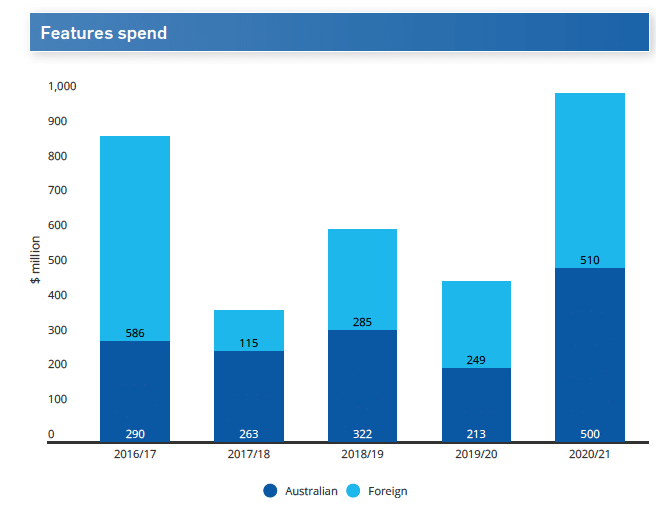

In 2020-21, there were 42 Australian features and 22 foreign. Those numbers are almost spot on the five year average. But the total expenditure for the Australian films climbed from an average of $317 million to $500 million while the foreign films rose to $510 million against an average of $349 million.

So the feature film spend was just over $1 billion, compared to that average of $666 million. That is a huge record-breaking increase. The reason? More big films, all part of the merry-go-round of production which has come and gone several times in the history of international production.

The foreign features are Blacklight, Thor: Love and Thunder and Thirteen Lives. To that list SPA adds big budget productions Baz Luhrmann’s Untitled Elvis Project, Mortal Kombat and Peter Rabbit 2.

The whole picture can be seen in this one handy Screen Australia graph.

Production across Australia

Theoretically, in our state-based federation with regional cities scattered across very different economies and climate zones, our screen storytelling should be spread across the whole of Australia. Fat chance, of course, as the gravity well of power is centred on Sydney in the relentless dynamic of uber-urbanisation.

The numbers are all over the shop from year to year, partly influenced by the availability of studio space. This time round NSW had 45% of the shoots and 57% of the post production, followed by Queensland with 34% an 15%, Victoria with 15% and 20%, South Australia with 4% and 8%, Western Australia with 2% and 1%, and the rest of Australia with 1% and 0.

That is not a very good indication, although the proportions are pretty consistent. The percentage of companies owned in Sydney is far higher than the production level, states are tending to specialise, the match of available people and opportunities is invisible, and we can even wonder about the educational facilities and the number of emerging filmmakers. And active production companies.

The pub test about Sydney centralisation is true, but the real issues are about whose way of life and point of view gets to participate in the national picture, the available levels of experience for local production, and the opportunities for young people. Tasmania has been invisible for a long time, but is now getting a solid level of production, but the place is being redefined as a place of creepy horror or quirky comedy. Good or bad?

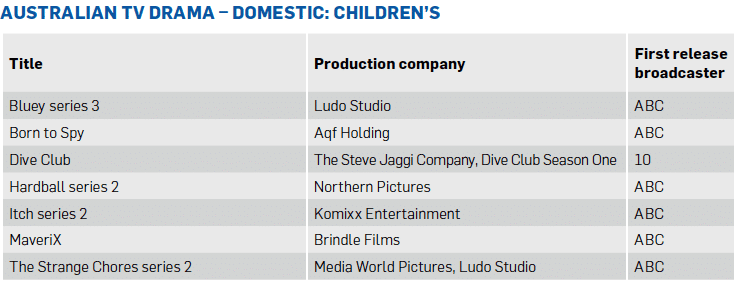

Children’s television

This sector is a nightmare, as we know from the way in which the Federal government has let the commercial networks off the hook. As SPA says, ‘Whilst there is stability in the top line investment figures, the total number of titles and the total number of hours have both approximately halved. This represents a fairly significant structural change, with fewer opportunities for production businesses and confirms feedback received from SPA’s members regarding significant upheaval in the sector.’

Read: Children’s sector confronts government, politely

The Screen Australia analysts notice that ‘Hours, budgets and spend were all down on the previous year – 56%, 23% and 6%, respectively. Cost-per-hour, however, increased by 74%, and was 53% above the 5-year average.’

Every production was supported by the agency, which mandates a minimum license fee. So these are the blue-chip shows, dominated by the ABC, and most likely to secure international sales. That indicates the absolute importance of the ABC children’s funding, the pressure to go global and the collapse of lower budget animation series. Except for Bluey, our national treasure.

Here is the story in a chart.

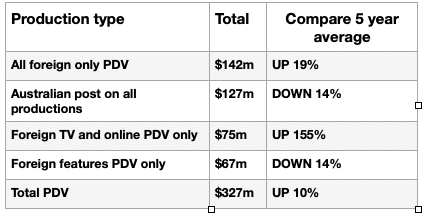

The Post, Digital and Visual Effects slate, aka PDV

Here the icy grip of historical statistical methods disappears. and expenditure is spread across the total period of the work rather than a single day.

Total expenditure is $327 million, which is 10% above the five year average. The foreign shows took $142 million, which is a substantial increase of 19% on the five year average. :Pull out the TV and on-line dramas and we discover that the five year average is beaten by 155%, and totals $75 million.

But the feature side drops by 25% on the average, and the Australian productions are down 14%. However, the comparison reveals that

According to 2016 figures from the Bureau of Census and Statistics, these figures are probably around 60% of the total PDV work which includes commercials, sports coverage and studio shows.

Feature film budgets

I’ve kept the most incendiary figures until last.

Ypu can see the impact of the delayed production, scooped out from 2019/20 and fed into the current total of $510 million. The number of Australian titles is pretty stable, but the foreign figures can move around like iceblocks on a stovetop; at the moment they are bolstered by COVID, the cost of the Australian dollar, and the bottlenecks caused by the rise of the streaming companies.

The sub $1 million feature space has pretty well disappeared, from 19 to 2 in five years.

The sub $1 million feature space has pretty well disappeared, from 19 to 2 in five years. There are 22 features, or 55% of the total budget in the $1-5 million space, 9 or 24% between $5-10 million, and only 6 or 16% over $10 million.

We are still stuck under $10 million and those 23 films under $5 million are particularly frustrating. That represents a significant overall decline in available feature budgets because costs are going up and inflation is biting. If we need to spend money to make money, we are not spending enough. I am sure the same can be said about marketing.

The future

This is happening at a weird time. We can’t expect the agencies to provide more because they are overstretched already. Cinema exhibition is spongy as COVID continues, and the number of tentpole films is declining as they move to streaming – so there is more space for indy films, just as the budgetary pressure climbs and producers want to increase quality.

Whether this pressure bursts sideways is impossible to predict. We can expect some to find foreign money and trade away intellectual property, the streamers will pick up bits of it, creative people will move into long form television. These are good trends, not bad.

But the loss of IP attacks the resilience of the sector, the streamers are probably too conservative, and we keep on outsourcing artistic daring to emerging creators.

the loss of IP attacks the resilience of the sector, the streamers are probably too conservative, and we keep on outsourcing artistic daring to emerging creators.

Meanwhile, SPA continues to fight against the decline of the local television and kids’ market which we see in these figures. Screen Australia notes the solid slate of international films, while Graeme Mason acknowledges that there will be a dip because this year has been superheated by those delayed productions.

For the next few years we can expect the streaming companies to deliver opportunities, as they struggle to find the space and crews to make shows. If anything, many crews around the world are inexperienced and underdone.

It’s a good time to bet on work, but maybe not a career in Australia.

Read: Less TV, more companies