Right now, the story of the sector is a question of scale. Image: Pixabay

For a producer to work on a successful production, there is one sure-fire rule. Work for a big company, though it will not be your money and you won’t own the IP.

We now know that the companies with more than $25m in revenue always make some sort of profit across an annual slate, while 95% of companies taking between $1m and $25m are making a profit, and 22% of companies making less than $1m are making a loss.

Here is a startling figure: the $25m+ companies turn over a total of $589m/year and 70% of that income comes from unscripted programs.

These figures come from the Deloitte Access Surveys prepared for Screen Producers Australia, which many people will remember filling out a few months ago. Besides SPA, Media Super, Film Victoria, Screen Queensland, the Australian Film Television and Radio School and Create NSW were all involved.

This is the first time that the industry has produced an analysis of the issues seen from inside, so it is entirely about the independent sector. Ironically, it is a political tool so it is written in the language of Treasury and macro-economics.

The power of size

These conclusions tell us that there are a lot of companies turning over tiny amounts, and by the time a company is turning over a million, its chances of breaking even are much higher. The figures are not broken out in detail but we would expect a close correlation between increasing turnover and increasing profit. Bigger really is stronger.

The independent production sector spends at least $1.2b/year. 43% of companies export, and the total is $163m/year, which is 14% of the total revenue. $119m or around 79% of that was made by companies earning over $25m. Companies turning over less than $1m made a collective total of $183,000 in export revenue. But as the report acknowledges, they really need it.

Bigger is not just stronger, it is doing better internationally, as reflected in those export numbers. They have transcended the constrictions of the domestic market.

Three types of company

The report breaks the sector into three categories: sub one million; one to $25m; and over $25m. At first glance this is a weird arrangement. At the bottom we have a bunch of companies that occasionally make programs which vary from once every few years to a steady trickle. The producers may work often for other people, or hire equipment, or work outside the industry.

This is a very interesting sector in terms of emerging producers, imaginative use of the internet, and ultra-low budget production, and it breeds different visions and approaches. Producers who use philanthropy to fund production, for instance, would see profit as a meaningless term.

But the numbers are not kind. The category accounts for 59% of the businesses, while they control less than 1% of the total cost of Australian independent production.

The one to 25m space is huge. Almost every successful Australian company in regular production will fit inside those numbers; their stability and profitability probably increases in sync with turnover so we derive a simple rule. Bigger is better and more stable and the idea of disrupting successful micro-companies is largely a myth.

Above the $25m bar, the companies have worked out how to service a commercial TV or cable market with long run low budget factual or reality shows. Beyond is an Australian listed production company, and CJZ proudly calls itself the largest independent Australian production company. Up at that end, Endemol Shine Australia and FremantleMedia are overseas owned, like most of the larger drama outfits.

We have to be careful about the language. Production revenue is the total value of the production budgets over a year and is a great measure of activity. However, companies also have additional revenue from sales, licenses and format deals, along with a category just called other.

Exports

Australian projects are sold into at least 225 territories. But look at the proportions: $83.4m came from the UK; $46.1m came from the US; $9.5m came from Europe and $1.7m from the whole of Asia. No figures for Africa and Latin America. [In other words, we are basically selling entertainment to 10% of the world’s population.]

The question of how much work is actually created by production is messy. Government press releases talk about creating a stupendous amount of work, which really equates to extremely short term production jobs in which an extra for a day counts as one. The report gets around this by talking about production roles, which is a measure of the full list of credits. It claims there are about 1,300 long term roles in the independent sector, and 18,000 production roles, so about 90% of the roles are short term.

Unscripted

Remember that 70% of the income for companies turning over more than $25m a year comes from unscripted production. They make cheap factual programs, game shows, and panel shows – anything that can rely on voluntary talent, studio shoots and a popular front person. Location shoots are poison.

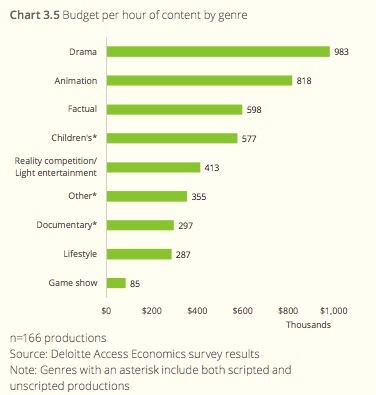

The dominance of unscripted shows at the top end of the market is made even more complete by the fact that drama costs around twice as much as reality competition/light entertainment. This diagram is very instructive:

The television companies, including the ABC, are trying to reduce costs per hour, which explains why they want to replace drama with shiny floor shows and game shows. So the companies that make them, fuelled by foreign formats created by their owners, have an advantage on a per hour basis, but they make more shows per week so they profit from the volume. Do cheaper but more of it is one of the basic survival rules of television production.

The labour component of drama is higher than those cheaper staple shows, so running game shows rather than cop shows is a way of cutting the amount of labour per hour which will contract the size of the sector. The tendency to do them in house makes the problem even worse for the independent sector. At least, says the report,

The screen industry is well balanced from a gender perspective – 55% of employees who are permanently employed in production businesses are female. Two thirds of production businesses responding to the survey had more female employees than male in 2017.

However, that is a bit ingenuous. We all know that the figures in general trend male, so the predominance of women in stable employment means the freelance sector is even more skewed than we thought.

Australian voices

The report claims that 90% of the ideas in the sector come from Australia. It is speaking in very broad terms, since the number of ideas in a production company is like the real length of the coastline. Almost everything is an idea by someone, just as measuring every bay and delta creates an enormous number as well. Here we are saying that one show = one idea, so the actual number of ideas per year is not large.

This figure looks pretty good, but it comes with a big problem.

5% of the ideas for scripted shows come from overseas, while three in every ten unscripted ideas are imported. We buy a lot of formats. Remember that formats underpin the cheapest types of production, made by the most profitable companies, creating the most hours of television.

Then we can see that the total percentage of television watched by Australians which actually comes from here is a lot lower than we think.

Commissions

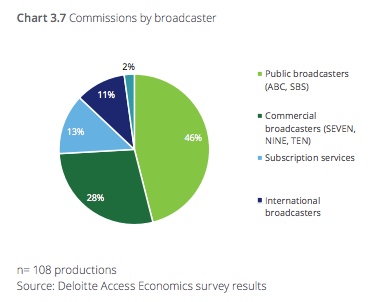

There is a lot of noise about the need to protect and enable the various sectors of the broadcast industry to increase Australian production, particularly drama.

Here are the actual percentages:

In all fairness, these figures don’t correlate directly to production, because the commercial broadcasters also commission internally in areas, which are left out of this discussion. But it is clear that the ABC and SBS lead the sector, even though its total revenue is about the same as Network Seven, and the taxpayer gets a lot more services for the money.

What about the future?

Australian producers are facing the rush of VOD from overseas, led by a triumphant Netflix. Commercial TV revenues are declining, commission prices are dropping too, the government broadcasters propping up drama are under attack, and monetising small screen use is tricky.

Doesn’t look good. And yet, 80% of companies are fairly bullish about the next five years, and we would expect that the despondents would cluster at the low budget end, which is fluid anyway. A lot of older people will also leave in that time.

The report has headlined the fact that the sector is better at exporting than the general business landscape [presumably excluding minerals and agriculture], but there is a sting in the tail of that fact. Says the report..

However, this is actually a fairly low proportion when compared to businesses more broadly. Other recent business surveys show a much higher proportion of businesses (85-90%) are positive about the future (Deloitte Access Economics, 2017). In fact, 21% of production businesses responding to the survey expect to reduce their activity in the next five years, and almost one in ten production businesses are concerned about their solvency in the future.

Smaller production businesses are more likely to be concerned – one quarter have a negative outlook over the next five years. Even among businesses with more than $25 million in revenue, the outlook is less positive than the average business across the economy (Deloitte Access Economics, 2017).

Small v big – the policy question

Take emotion out of these figures, and the conclusion seems obvious. Big is better, big fits the financial changes in broadcast more closely, big offers longer term stability.

But the survey also allows us to ask whether betting on big is the way to support Australian culture and Australian stories. Big is enabling the race to the bottom, and big is ultimately controlled from overseas. Big is neither nimble nor creative. We only have to look at the struggles of Nine and Ten to survive in the manner to which its executives have been accustomed to realise that scale is no protection.

It would be wonderful to read a survey which looks much more closely at that question of ideas. Where do they actually come from? Was it the wetware between the ears of someone in fine linen playing with the silverware at a corporate planning day, or was it housed by some group of much younger people with their laptops next to the toast in tiny shared office?

We know who buys them, but who does the selling?