Image: Indian women wrestling film Dangal.

Overseas streaming services really want to get into China, but the government has a healthy Communist understanding of the power of media in creating the world in which the masses live. So, no deal and the big networks have to content themselves with licensing content to Chinese streaming services, which can only run after a combersome process of approval by the government.

Netflix did this with iQIYI in April 2017, though this is a poor cousin arrangement. It gets a licensing fee, but not subscription income. iQIYI has at least twenty million subscribers, which is a tiny number for China, and the company also has deals with most of the other big English language names, including the BFI.

Now, the other side of the deal is coming home to roost. Government policy mandates that the relationship with foreign companies is not about imports but exports. China wants to sell material internationally, partly to the diaspora. While the West’s attitude to propaganda is largely unconscious, and fails to notice the crude way in which it promotes our culture, the Chinese structure understand how soft power works in the media.

Netflix is going to run Youku Tudou’s Day and Night, a drama called Tientsin Mystic and crime series Burning Ice. Chinese producers now have access to up to 190 countries depending on the licensing deals. So, in the broadest way, Netflix is now a system for transmitting Chinese cultural propaganda to the world.

——

The censorship restrictions published by SAPPRFT, the Chinese State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, are strange to Western eyes, and potentially dangerous. According to Forbes, one of the provisions relates to ghosts.

4) Showing contents of murder, violence, terror, ghosts and the supernatural; distorting value judgment between truth and lies, good and evil, beauty and ugliness, righteous and unrighteous; showing deliberate expressions of remorselessness in committing crimes; showing specific details of criminal behaviours; exposing special investigation methods; showing content which evokes excitement from murder, bloodiness, violence, drug abuse and gambling; showing scenes of mistreating prisoners, torturing criminals or suspects; containing excessively horror scenes, dialogues, background music and sound effects;

That is enough to show that the rules are very subjective and anti-dramatic.

But they are remarkably similar to the Hays Code, signed in 1930, to bind Hollywood to conservative morality.

XII. Repellent Subjects

The following subjects must be treated within the careful limits of good taste:

1. Actual hangings or electrocutions as legal punishments for crime.

2. Third degree methods.

3. Brutality and possible gruesomeness.

4. Branding of people or animals.

5. Apparent cruelty to children or animals.

6. The sale of women, or a woman selling her virtue.

7. Surgical operations.

They both seem to occupy a common place that bestrides the world – the Uncelestial, Undemocratic Republic of Bureaucracy (UURB). Both systems demean filmmakers, lead to a lot of fearful sweating, and require detailed horsetrading over individual frames.

Even the treatment of religion is similar on the surface.

China:

(6) Advertising religious extremism, stirring up ambivalence and conflicts between different religions or sects, and between believers and non-believers, causing disharmony in the community;

USA

1. No film or episode may throw ridicule on any religious faith.

2. Ministers of religion in their character as ministers of religion should not be used as comic characters or as villains.

3. Ceremonies of any definite religion should be carefully and respectfully handled.

In fact they are polar opposites since the Communist Party is hostile to religion and great chunks of Thirties Hollywood actively promoted the Bible.

Hollywood has never had a problem with ghosts and supernatural stories, but the Chinese government has banned films like Ghostbusters and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. Officially, this is to do with the ghosts.

However, the Chinese did allow Coco into the country. It has taken US$76m in two weeks, against US$115m in the US. The take around the world is now US$288m. The Western trade press has been a bit astonished by this, because the rules seem to be inconsistent. Of course they are bent all the time in the UURB. Ghosts are deeply embedded in Chinese culture and turn up in many films. It is a big deal only because Hollywood wants consistency on such a major motif in Western scarey films.

One theory says the UURB officials were so moved they let it through; another says that the aspirational theme of a young person becoming a good citizen was enough. But I, with the temerity of ignorance, wonder about another factor. The Chinese government is busily warping its past to create a national story and identity embedded in its past. The role of women in history films is one obvious and mindboggling example. Coco is a film about honouring ancestors, part of the glue that holds this rickety story strategy together. What’s not to like?

——-

The AFI/AACTA now has an award called the AACTA Award for Best Asian Film presented by PR Asia. Given the scale and diversity of Asian cinema, its emphasis on commercialism, and the tiny attention that we command in the discussion, this seems like a pretty peculiar idea. We will see how it develops.

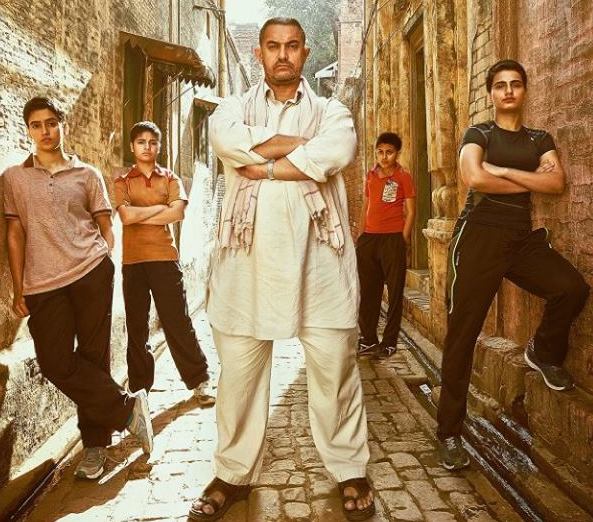

The inaugural winner is an Indian film called Dangal, made by Aamir Khan, Kiran Rao and Siddharth Roy Kapur. It is a contemporary film, based on a true story, about elite women wrestlers. The poster seems to have no women in it at all, which speaks to the touchiness of folks in the Indian street.

Here is an interesting fact about Dangal. Since it was released last December it has made US$12.4m in North America, and US$1.45m in Australia. The UK figure is surprisingly low, at US$2.8m, while the UAR had US$6m.

In its home territory of India, it has made US$77.3m. But in China it has taken US$193m.

There is an enormous market across Asia which we don’t even notice.

——-

UPDATE: James Nolen pointed out on Facebook that all the people in the Dangal poster except for Aamir Khan are girls. He is right. So much for my quick racism about the rise of Hindu fundamentalism. This time round I also watched the trailer, which reveals the whole anti-sexist storyworld and is released by Disney.

Here is the relevant part of the poster –

And the trailer.

UPDATE TWO:

In the original version of this article, I referred to Hindi women. ArtsHub is a multicultural office and I have been told that this doesn’t work because the English language trick by which we can talk about the English language and English people doesn’t work grammatically in Hindi.

UPDATE THREE:

Liz Shackleton in Screen Daily explains the success and covers the marketing strategy.